Movie Review – Four Musicals It’s Okay To Love: West Side Story, The Sound Of Music, Singin’ In The Rain & Moulin Rouge!

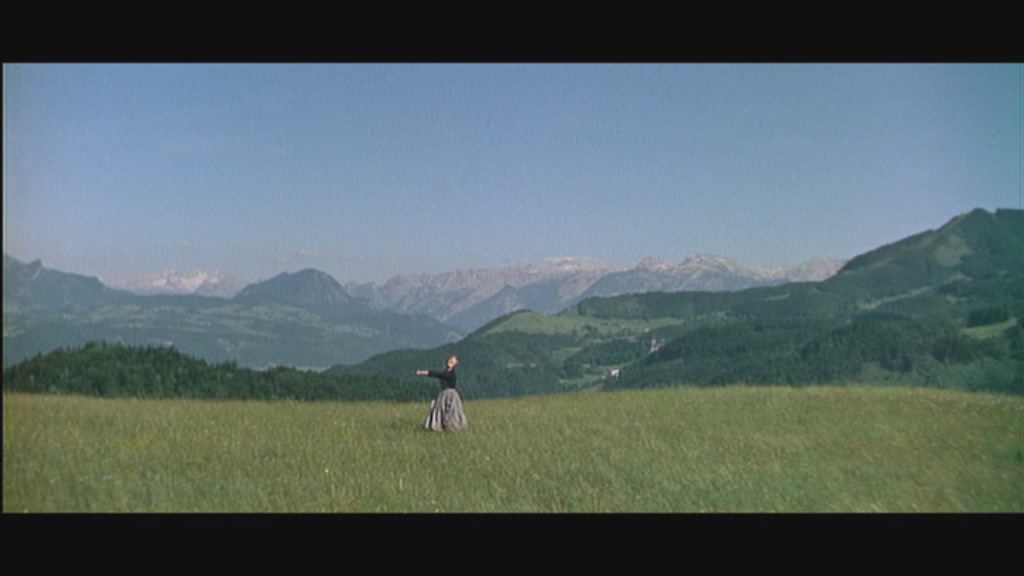

We drop down through grey mist, through clouds. We hear an icy whisper of wind. Mountains below: slabs of granite, peaks gashed with snow. Then a lake, the boats gliding along its shoreline tiny enough to give us vertigo in this Panavision, this early (and many say visually richer) version of iMax: we’re still at a great height. A bird sings, then sings again; a piccolo calls and responds. We soar across staggered hills, over dark clutches of pines. And finally, on the wing, on a rising sweep of music, of French horns and strings, we come up on a high Alpine meadow. A young woman is striding toward us, dressed in a coarse black dress, a practical grey apron. Her cropped hair shines golden in the sun. She’s tall, slender, long-boned. She opens her arms to the glorious day surrounding her and sings

The hills are alive with the sound of music.

She is Julie Andrews, and this is her second appearance in a major motion picture. (The film’s producers at Fox hesitated about casting her– though Andrews was a seasoned stage performer, she had never appeared in a color film, let alone a film on the scale of this one– until they persuaded Disney to allow them to see rushes of her in Mary Poppins, which at the time was still in production.) At this moment, in 1965, she is at the height of her power as a singer. She’s sung professionally since the age of seven; hers is an astonishing four-octave range. At the age of twelve, she performed for the Royal Family of England, and now she is the queen of the musical stage, having originated the roles of Eliza Doolittle in My Fair Lady and Guinevere in Camelot. Her coloratura soprano is as clean and clear as the stream she steps across now, here in the Alps.

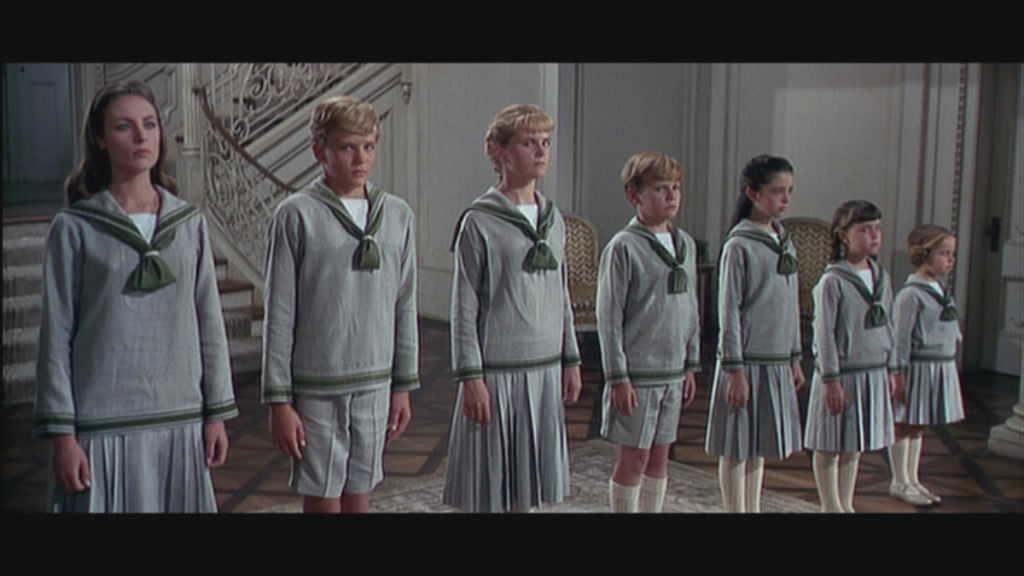

I’m not sure how much explanation we need for The Sound of Music, in terms of background or plot; I’ve loved the film for so long– going on four decades now (oh, my God–!)– that I can’t conceive of anyone not being aware of it, or being aware of it for itself and not as an object of camp or parody. Here, a bit of background: The movie, roughly, with Broadway’s and then Hollywood’s eye for storytelling practicality, is based on the real-life Trapp Family Singers. Georg Von Trapp was a captain in the Austrian navy; a widower, he’s been left with seven (SEVEN!– and Ernest Lehman’s script provides appropriate moments of shock over that fact) children; Maria (here Andrews, on stage Mary Martin), a young novitiate at a local convent whose rambunctious ways (she’s playing hooky when we find her singing high up in that mountain meadow) call into doubt her suitability to become a nun, is sent to act as governess to the Von Trapp children. In short, in the film as in real life, the children grow to love her, the Captain does, too, and a newly married Maria (she was less newly married in real life, but that’s the economy of Hollywood and Broadway for you) and her family escape over the mountains into Switzerland when the Nazis demand that the Captain accept a commission in the German navy, right at the start of World War II.

What grounds these films– these grand, classic, ultra-widescreen musicals– is, in fact, just that. Both The Sound of Music and West Side Story have deeply real external settings. Those settings are as unalike as it’s possible to be: The Sound of Music finds its heart in the soaring crags of the Alps around Salzburg, Austria: rolling meadows, the bristle of pines, the deep grey-blue of lakes sparkling under high-altitude sunshine. In West Side Story, in contrast, we see not even a single blade of grass, the green of the parks and campuses over which we fly in the film’s opening minutes being utterly alien to the world we’re about to visit: the Lower West Side of Manhattan in the early sixties is boxed with tenements, bound by rivers of stained pavement and cracked sidewalks, rattling with chain-link fences.

The Sound of Music is, rightly enough, a triumph of music on film. As arranged by Irwin Kostal for a seventy-piece orchestra, the all-American oompah of the Rodgers and Hammerstein song “My Favorite Things” becomes something like the lead entry in a sweeping new canon of Strauss waltzes. In contrast, songs like “Edelweiss” and “Something Good,” in which Maria and the Captain wryly but tenderly confess their love for one another, bring intimacy to the picture without shrinking its scope.

Musicals are the hardest “sell” for a movie audience. We can accept spaceships and aliens, superheroes, supervillains, slam-bang stunts and special effects, but we less willingly suspend our disbelief when it comes to watching someone burst into song on screen. (Another matter still, and not one I’ll be discussing in detail here, is how willingly we accept that people will simply burst into song on stage.) Part of what enables us to suspend our disbelief regarding The Sound of Music is not only the fact that Andrews sings like it’s the only possible thing a benevolent deity might have put her on the Earth to do but the fact that Christopher Plummer, who plays the Captain, is one of us: he brought a healthy sense of cynicism to the set, a wariness. He insisted that the Captain should have a flinty edge and a droll sense of humor; screenwriter Ernest Lehman obliged him. Plummer had a capable voice, but he wasn’t a singer (his songs were dubbed after the fact, much to his surprise and disappointment, and that of his co-stars; it’s uncanny how neatly his vocal stand-in matches his timbre), but he was a highly trained stage actor, and onscreen in 1965 he is strikingly, hawkishly handsome, with eyes of the sort of piercing blue for which rich, hyper-realistic color processing like Todd-AO was ideally suited. (In the film, he looks exactly like the picture of Alexander Hamilton currently printed on the U.S. ten-dollar bill, but that’s just my opinion, and I’ll admit it’s a strange one.)

Rich without ever seeming garish, an absolute celebration of music with realistic, panoramic settings, The Sound of Music is the pinnacle of film musicals. You’ll forgive the sugary sweetness of the story for the beauty of it. A wide-swinging comparison, perhaps, but if The Dark Knight were a musical, and a musical about a family, for families, and that musical ended on a high note (literally: the last shot of the The Sound of Music sees the Von Trapps hiking along the grassy, windswept crest of a mountain on their way into Switzerland), it would be The Sound of Music. The film, with a budget of eight million dollars, went on to gross nearly $170 million following its initial release in 1965. Without the Internet. Without chatboards and viral marketing. Without DVDs or CDs or Blu-Ray.

With nothing but those great craggy Alps, too many children, a cranky Canadian, and a lanky young British actress, a theatre veteran with the voice of an angel.

West Side Story, which won eleven Academy Awards in 1961, is nearly, as I noted above, as unlike The Sound of Music as it’s possible to be. The most striking difference, aside from the settings, the documentary sweep and natural grandeur of The Sound of Music versus West Side Story’s unrelenting inner-city grit, is in the music: Richard Rodgers’ score for The Sound of Music is pit-band friendly, all easy keys and simple counterpoint. Leonard Bernstein wrote the music for West Side Story, and he couldn’t have given less of a damn about the comfort of the show’s accompanists. He was a brilliant composer and conductor; as the music director of the New York Philharmonic, he was accustomed to working with the best of the world’s best musicians. Time signatures that don’t occur in nature, blinding flurries of thirty-second (and sixty-fourth!) notes, syncopations that can throw your back out if you’re not careful: his score for West Side Story is full of them.

But the effect is electrifying.

It’s a story of violence, violence in itself and the tender violence of doomed love. Here, in terms of drama, is where West Side Story and The Sound of Music briefly cross paths (and where West Side Story in turn crosses paths with Moulin Rouge): love. Love that damns us, saves us, transforms us and our lives. Love that can kill.

West Side Story is Romeo and Juliet updated for the gang wars of New York in the 1950s and 1960s. We could say the gangs could be any gangs, in any city, in any decade; here, they’re the homegrown Jets, Caucasian– Italians, Irish, Poles, Germans– and the Sharks, Puerto Rican immigrants. They speak in the street slang of the sixties, and at first those “Daddy-O”s sound strange, until you remind yourself that all gangspeak is automatically insular, just as automatically quaint and dated. At a gym dance, Tony (Richard Beymer), a former Jet and best friend of the Jets’ current leader, Riff, meets and falls in love with Maria (Natalie Wood), sister of Bernardo, leader of the Sharks. They fall, of course, with movie-style immediacy, but Richard Beymer and Natalie Wood play the scene with believable, dreamy incredulity; in the film, as in the stage play, the world around them fades away as they shyly approach one another across the floor of the gym.

Critics have said that brown-haired, brown-eyed Natalie Wood doesn’t look sufficiently Puerto Rican as Maria; I’ll argue it against them. She looks fine. If nothing else, Wood brings a workable combination of spine, spark, and wide-eyed innocence to the part. She’s beautiful. Maria tells Tony he must stop an impending fight between the Sharks and the Jets, and stop it absolutely, even though he’s already worked to downgrade the battle from a general melee to a match-fight between Bernardo, the best of the Sharks, and Ice (lean, angular Tucker Smith), who’s to represent the Jets. In short, Tony gets himself trapped between the gangs, Riff is stabbed and killed, and then Tony himself, in anger and confusion, stabs and kills Bernardo. As in Romeo and Juliet, best intentions lead to tragedy.

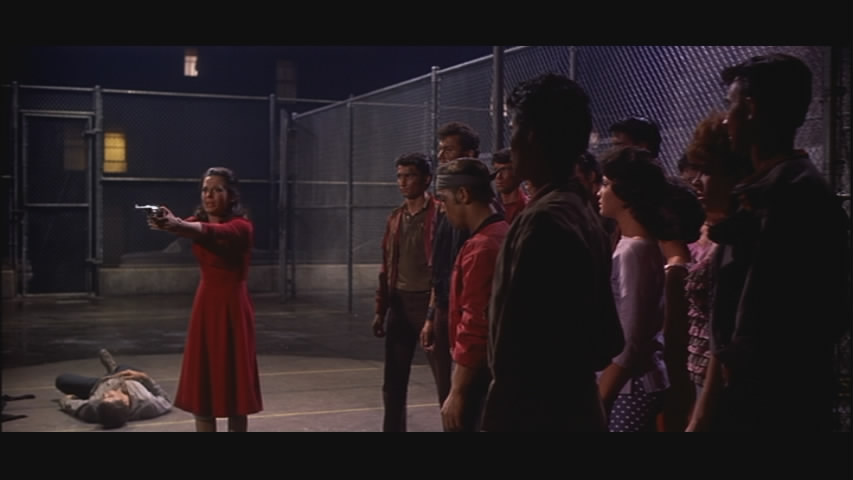

And, as in Shakespeare’s version, the tragedy doesn’t stop there. In the end, Tony lies dying in an empty playground, gunned down by Chino, Bernardo’s faithful right-hand man. Tony, believing that Chino in fact killed Maria, is shot right as he and Maria spot each other across said empty playground; in the best tragic tradition, he dies in her arms while she does her best to keep him focused on the future they’ll have together (a reprise of the beautiful “One Hand, One Heart”: “Even death won’t part us now,” she whispers, as he dies– and if you’re not crying at this point, your heart is made of solid stone.).

A film has never blended dance, music, and raw emotion as perfectly as West Side Story. Maria, rising from Tony’s side, demands the gun from Chino; crestfallen, stunned, he meekly gives it to her. She points it at him, then at the Sharks and the Jets, who have gathered to watch; they step back in wide-eyed fear. “How many bullets are left, Chino?” she asks. “How many can I kill– and still have one bullet left for me?” Unlike Romeo and Juliet, though, West Side Story doesn’t present us with a lesson learned from the deaths of all its protagonists. Rather, it ends with a somber message of hope: members of the Sharks step in to help the Jets who are trying to lift Tony and bear him away; a Jet gently settles Maria’s shawl over her head like a veil, and she walks with dignity behind those who carry Tony, a symbol of newfound peace between the gangs. She and the gangs ignore Lieutenant Schrank (burly Simon Oakland) and kindly but weak Doc (Ned Glass), the owner of the soda shop where Tony worked. Chino is arrested, but the other teens leave: the adults in the film have provided them with little else than brutality or indecision, and they’ve found the path to maturity on their own. Maria explains it for them, for the Jets and the Sharks alike: Guns don’t kill. Knives don’t kill. Hatred kills. Now, at least for the time being, the gangs know enough to put their hatred aside.

It shouldn’t work. Never mind that dated gang dialogue: the producers expect us to buy into a story featuring gangs who dance and sing. But the grime of the settings grounds the movie; it takes only seconds to realize that what we’re seeing isn’t dance as such but a form of martial arts, beautiful and graceful, yes, but proud, athletic, and violent, too (especially in the person of Russ Tamblyn, who brings charm and acrobatic prowess in equal measure to the part of Riff); and Bernstein’s score is difficult, jolting, playful, and gorgeous. In terms of setting, West Side Story couldn’t be less like The Sound of Music if it tried, but they’re both masterpieces in the purest sense of the word.

In a less-pure sense of the word– but meaning no disrespect, and certainly with nothing less than the greatest affection– we find Moulin Rouge. In 1965, The Sound of Music literally saved 20th Century-Fox: after throwing twenty million dollars (at the time a sum beyond astronomical) into Elizabeth Taylor’s Cleopatra, which was to be the studio’s greatest bomb, Fox stood at the brink of bankruptcy. The Sound of Music brought a flood of money to the film’s coffers, saving the studio from disaster; now it’s thirty-six years later, and Baz Luhrmann is kicking off Moulin Rouge, his ode to bohemian living in the Paris of 1900, with a musical nod to the film that kept Fox viable.

Young Christian (Ewan McGregor) has come to Paris from London to write about the “bohemian ideals”: freedom, beauty, truth, and love. There’s just one problem, thinks Christian, our narrator, as he sits in his high garret room, he’s never been in love. He’s stumped. Fortunately (please add question marks to taste), at that moment an unconscious Argentinian falls through the roof of his room, and Christian finds himself in the midst of a rehearsal for an as-yet-unfinished (in fact as-yet-largely-unwritten) musical to be staged by artist Toulouse-Lautrec and his friends. They’re at creative loggerheads, and not just because their lead, the Argentinian, is narcoleptic. They bicker over lyrics; Christian, trying to be heard, finally belts out in song out the words he’s been trying to make them hear:

The hills are alive with the sound of music.

There’s irony here, but not mockery. The joke of the scene lies in the reaction of Christian’s new artist friends: his words are, they insist, the perfect embodiment of their revolutionary artistic creed– Truth! Beauty! Freedom! Love!– and Luhrmann incorporates “The Sound of Music” into his brash new movie with the purest enthusiasm, with nary a trace of a wink or a nod. McGregor, to his credit, sings with great enthusiasm and sincerity. That he can’t sing worth a damn (at times, he and key signatures are but distantly acquainted) doesn’t matter in the least. Unlike Gerard Butler, another non-singer cast in a musical, who butchered the big-screen adaptation of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s The Phantom of the Opera by shouting at the songs until they went away, McGregor is perfectly cast here: he’s the rare modern actor who can be innocent and wide-eyed without seeming callow. When Satine, the Moulin Rouge’s star attraction, a courtesan who leads the theater’s cabaret performers, tells him she can’t fall in love, a smitten Christian blurts out “That’s terrible–!”, and we sense his sincerity even as we understand what he, for now, does not: Satine can’t fall in love because falling in love is “bad for business.”

But fall she does, both romantically and, by the film’s end, fatally. Satine, you see, is dying. A bearded, bedraggled Christian tells us so right at the opening of the film, before the flashback that begins the story proper. He tells us flat out: “The woman I love is dead.”

By modern standards, this is a very daring move on Luhrmann’s part. (Never mind the critics who immediately invoked the shades of La Boheme and a dozen other tragedy-centered operas; I think it was kind of them to stop by, and they wouldn’t be yowling if Luhrmann’s film hadn’t struck a nerve.) Moulin Rouge is a whirl of color and motion, a wonderful jumble of music, quick-cut editing, and photographic effects. To base the whole thing on a tragic tale took guts, to put it bluntly; sure, Luhrmann had filmed a modern take on Romeo and Juliet, but there death is no secret: everyone knows that story. Here death comes as a surprise, and its prevalence in the movie, when you sit back from the flash and motion and bombastic sound and think about it, is amazing: the death of a century, the death of a way of life, that of the garish, exuberant, freakish world of the Moulin Rouge and its inhabitants, and the death of the woman on whom, for our purposes, that world depends.

That woman, Satine, is Nicole Kidman. Like Ewan McGregor, she is not a singer. She and the key nod at one another in passing, in any given song. But, like Marlene Dietrich, who well understood not only the strengths but the limitations of her dusky voice, Kidman knows how to put a tune across. She vamps dazzlingly in Satine’s showcase number, “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend,” and she and McGregor knock the lid off the heights of heartbreak when they sing the film’s show-stopper finale, “Come What May.”

(A note regarding “Come What May”: in the annals of Academy Award injustices, the passing-over of “Come What May” for Best Original Song ranks in the top ten. It’s eminently singable; it’s shamelessly tuneful and romantic. Partly, though, its snubbing was Luhrmann’s fault: he’d written the tune for his updated Leonardo DiCaprio/Claire Danes Romeo and Juliet, then decided not to use it for the Romeo and Juliet soundtrack. According to the nitpicking bylaws of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, then, “Come What May” was not “original” as far as Moulin Rouge was concerned– even though the song had never before been used in any medium. Ridiculous– and an utter pity.)

The obvious comparison here, since we’ve noticed Shakespeare lurking in the wings, is with West Side Story. There we lose Tony– or Romeo; here, we lose our Juliet in the person of Satine, doomed by that most romantic of deadly catch-alls, consumption. But the films are at their core extremely different. Certainly, both of them are bursting with energy; certainly– if you’re anything like me, anyway– they’ll leave you emotionally sapped but purified (which is a fancy way of saying you’ll cry your damn eyes out, but you’ll be glad you did). But West Side Story is a triumph of musical composition: Leonard Bernstein basically takes Sergei Prokofiev’s ballet of Romeo and Juliet and puts the music on modern jazz-beat steroids. Moulin Rouge, on the other hand, hasn’t a single original song– save for “Come What May,” as noted above, and even that one ended up labeled a loaner– in its nonetheless sincere heart. The musical numbers are a pastiche of popular songs: in addition to songs by Rogers and Hammerstein, we hear ditties penned by David Bowie, Nirvana, Queen, Paul McCartney and Wings, the Police, a dozen or more others. It works, cleverly: Luhrmann and his cast (most notably Jim Broadbent, as Harold Zidler, the owner of the Moulin Rouge, a showman supreme) bring life and sincerity to the film’s soundscape. But this makes Moulin Rouge, unlike West Side Story or even The Sound of Music, less a musical than a popular entertainment. And that, ironically, makes Moulin Rouge more like the oldest of the musicals in the group we’re looking at today: Singin’ in the Rain.

“Singin’ in the Rain,” the song, was written in 1929; like Moulin Rouge, Singin’ in the Rain-– the film, now– engages its audience through the use of popular tunes. Of course, the songs popular in the twenties and thirties were better known to the audiences of 1952 than they are to us today, but they’re dandy ditties nonetheless. (Oddly, though– and this is an aside– I know “You Are My Lucky Star” best from its use in Alien, from the scene late in the film where a terrified Sigourney Weaver whispers the lyrics like a mantra to keep herself focused.)

Also like Moulin Rouge, Singin’ in the Rain deals with the death of an era: here, silent film. But the death stops there: we’ve moved out of the realm of musical tragedy (or a poor man’s Madam Butterfly, perhaps) and stepped into the sunlight of musical comedy. (In a film with “rain” in the title, mm hm: yes, I saw that one coming. Sure I did.)

Singin’ in the Rain is cheerfully obsessed with deceit. In Moulin Rouge, Satine at first mistakes Christian for the tightly wound, foppishly lascivious Duke who is to fund the film’s centerpiece play (and who sees Satine as a “bonus” for his willingness to invest); later, she and Zidler pass Christian off to the Duke as the writer of said play; later still, Fantine strings the Duke along while meeting with Christian, romantically, on the sly. Here, now, the lies are more blithe and boldfaced, if more MGM-innocent:

As the film opens, the superstars of Monument Pictures (not at all a pass at Paramount, I’m sure), Don Lockwood and Lina Lamont, arrive at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood for the premiere of their latest picture, a costume melodrama called The Royal Rascal. The year is 1927, and Lockwood and Lamont are at the height of their popularity as an onscreen romantic duo. On the red carpet, a radio gossip columnists asks Don, flanked by Lina and his best friend, Cosmo Brown, to regale his and Lina’s adoring fans with the story of his life; eyes twinkling, his teeth flashing in a rakish grin, Gene Kelly– Don– proceeds to spin a whopper.

He and Cosmo, says Don, grew up together. They attended the finest academies of music and dance (which we see as a string of smoky pool halls and beer joints). They also attended the theatre (as the boys duck past the box office at the local cinema to sneak into the latest silent potboiler). They played the finest venues (in towns with names like Dead Man’s Fang, Arizona, and Coyoteville, New Mexico). Don and Lina’s chemistry was present from the moment they met (or at least her foot was present at his backside when he answered a snub with a snub: Lina treated him like dirt when Don was a lowly all-purpose stuntman in her films, but she was all too ready to get cozy when R.F. Simpson, the head of Monumental, offered Don a contract. “Are you doing anything tonight?” asks flashback-Don, the newly minted star. Lina shakes her head and takes his arm, smiling seductively. “Too bad,” Don says, smoothly freeing himself. “I’m busy.”).

The MGM sound crew of 1951 obviously had a ball recreating the cinematic soundscape of the late twenties. During the red-carpet interview with Don, the sound tightens and narrows; if you look away from the screen, you hear him as he– and his cheery bundle of lies– would have sounded on the radio. Then there’s the accurate– and ludicrous– depiction of Monumental’s efforts, in response to the gauntlet thrown down by Warner Brothers in the form of The Jazz Singer, to make its own talking picture in the form of yet another Lockwood/Lamont costume melodrama, The Dueling Cavalier.

“It’ll be a sensation,” beleaguered R.F. tells his stars and Roscoe, his even-more-beleaguered chief director. “Lockwood and Lamont: they talk–!”

“Well, of COURSE we talk,” Lina points out. “Don’t everybody?”

And R.F. and Rosco, Don and Cosmo all look at one another in stunned– and horrified– realization.

Let us pause for a moment of explanation. The transition to sound pictures in Hollywood cracked up against two basic problems. First up were technical limitations. Early recording equipment was tremendously clumsy, and the idea of sound editing or remixing was still a good distance off down the pike. Microphones were usually concealed– poorly– somewhere on the set, which often led to actors standing rigidly about, all the life and movement they’d enjoyed on the sets of silent films frozen out of them as they tried to stay in range of the recording equipment. The cameras themselves, which made an unholy racket, had to be housed in boxes or windowed wooden closets so that their rattle and clatter wouldn’t end up on the soundtrack. In Singin’ in the Rain, the set mike for The Dueling Cavalier starts out in a bush, migrates to Lina’s shoulder, and finally ends up stuffed down her decolletage. Why? Because she can’t talk into the darned thing to save her life.

Not that her talking into it helps in the long run. This leads us to problem two of the early sound era: the cognitive divide.

Hard to explain, maybe, to a generation that never knew the time before people onscreen talked without intertitles. I have trouble imagining it myself. Here, try this: Have you ever read a book, then listened to that book on tape or disc? I, for one, grow accustomed to hearing my own voice in my head as I read; hearing someone else can be a real jolt (that doesn’t include the chorus of voices I hear in my head normally, outside of reading or books on tape, thanks kindly). If that someone else happens to be the book’s author, things can be especially jarring. We develop very particular impressions of how our favorite authors should sound, and the same was true– perhaps even moreso– of silent film audiences and the actors they loved.

For this reason, many actors making the transition to sound were rightly terrified. Darkly handsome John Gilbert, for instance, who was Greta Garbo’s co-star in a handful of smash hits for MGM, fell from the cinematic heavens when his too-ordinary tenor voice didn’t prove dashing enough for audiences. (Garbo herself soldiered on, her beauty and poise more than a match for her heavy Swedish accent, which actually came to complement her exotic mystique.) Alfred Lunt and Lynne Fontanne were among the stage actors– after all, stage actors knew how to talk all along, right?– recruited for the movies, as was lean, urbane Robert Montgomery, who became a staple leading man for MGM. But the fact remained: many actors didn’t successfully make the transition to sound. “What do you have to know?” R.F. insists to Roscoe, a little helplessly, as they contemplate making The Dueling Cavalier a talkie. “You do what you always did. You just add talking to it!”

Which leads us back to problem two, or, more specifically, for purposes of Singin’ in the Rain, Lina.

And Lina’s voice.

For Lina, actress Jean Hagen employs a vocal mix that sounds not unlike a cat being squeezed through a wringer on the New Jersey turnpike. Lina has so far gotten by on a combination of beauty (blonde, fresh-faced, wide-eyed, and utterly blank) and carefully orchestrated publicity: at all their public appearances (on the red carpet at the film’s opening, for instance), Don does all the talking for Lockwood and Lamont. But now the world will hear Lina’s ghastly voice. What to do…? Vocal coaching has no effect whatsoever; between Lina’s paint-scraper tones and a series of technical flubs, the test screening of The Dueling Cavalier becomes an early candidate for Mystery Science Theatre 3000-style reaming, as people in the audience hoot and catcall or walk out aghast.

Cosmo has the solution: why doesn’t Don look back to his vaudeville roots and make The Dueling Cavalier into The Dancing Cavalier, a musical? Young Kathy Selden (a nineteen-year-old Debbie Reynolds– yes, Princess Leia’s real-life mom), a charming and talented young actress who’s pal to Cosmo and Don, and who’s as smitten with Don as he is with her (rumors of a Lockwook/Lamont romance being just that: grist for the publicity mill), enthusiastically backs the idea.

Here we return to the idea of deceit. If Lina can’t talk, she certainly can’t sing. The solution? Kathy will re-record Lina’s dialogue and singing on the sly. Not only are we present at the dawn of sound, we’re witnessing the birth of dubbing, too. R.F. is keen on the idea, and things proceed melodically apace.

Until Lina finds out, of course. And not only does she find out, she proves a far shrewder businesswoman than she’d have been were Singin’ in the Rain made today. “What do you think I am, DUMB or somethin’–?” she demands, before outlining, with venomous sweetness, how she can take Monolith to the cleaners if R.F. doesn’t do exactly what she wants: not only is Kathy to go uncredited for The Dancing Cavalier, but Kathy will go on talking– and singing– for Lina for the entire five years of Kathy’s contract.

Not to worry, though. In one of the best literal reveals of all time, Lina gets what’s coming to her. Not fatally, of course: we’ll leave the death of anything other than eras to Moulin Rouge and West Side Story.

Bursting with Technicolor, sly, and very funny, Singin’ in the Rain is one of the last of the great Golden Age musicals. Like Julie Andrews in The Sound of Music, Gene Kelly here is at the height of his power as a performer. He’s not much of a singer– his singing voice is, as it always ways, thin but serviceable– but he’s confident and charming, and he’s a hell of a dancer. His is an effortless but muscular grace; like Hugh Jackman’s career in reverse, maybe, you’d believe that Kelly could have gone from being the dancing star of the silver screen to popping Wolverine’s adamantium claws from between his knuckles. A consummate professional, Kelly co-directed Singin’ in the Rain with Stanley Donen, so that he could bring a dancer’s eye to the film’s ambitious production numbers. (Similarly, choreographer Jerome Robbins shares co-directors’ credits with Robert Wise for West Side Story.)

The most unwieldy suspension of disbelief. The most emotionally moving– or devastating– cinematic experience: the melding of story with music. All different, all similar, all great favorites (and one or two other people might, I dare say, agree with me), these are four of the best musicals ever. Go ahead: like ‘em. Have a laugh. Sing along. And don’t be afraid to have a good cry. That’s certainly nothing to be ashamed of.

Although I enjoy the Sound of Music, I admit to one thing: It doesn't hold the same special. place in my heart regarding movies as West Side Story.

I grew up with SOM and only watched WSS after I'd "matured" as a film fan. So SOM has that special place….

I watched “Sound of Music” in a movie theatre, when it first came out, but “West Side Story” is my all time favorite movie, hands down. I never get tired of seeing it over and over again, especially on a great big, wide screen, in a real movie theatre with the lights down low. I still hold the opinion that a re-boot of this great, golden oldie but keeper of a classic movie-musical, West Side Story, is a horrible idea!

Having said all of the above, I can identify with a certain moving having a special place. For me, a movie with that special place is the 1961 film version of “West Side Story”.

I've seen "West Side Story" and "Sound of Music". but not "Singing in the Rain" or "Moulin Rouge", so I cannot compare the latter two films to WSS and TSOM. The commentaries on West Side Story and Sound of Music, however, are excellent and are full of things that I so wish I could say! Keep up the good work.

p. s. Here's hoping that Steve Spielberg's planned re-make of West Side Story never, ever goes through!

Thanks mplo, I agree with you re Spielberg's "Story" remake. What a terrible idea. And he's a director you'd THINK would know that remaking such a classic film is not just flirting with danger, but dropping your skirt and ASKING it to molest you.

Hi, Rodney. You're welcome! It's agreed–the idea of a re-make of such a great film as West Side Story is a terrible idea. A re-make of this classic would just cut the heart and soul right out of it.

Your way of phrasing this opinion is interesting…and funny, to boot. Thanks for the morning nods and chuckles of approval.