Movie Review – Lord Of The Rings, The: The Return Of The King

Principal Cast : Elijah Wood, Viggo Mortensen, Ian McKellan, Liv Tyler, Sean Astin, Sala Baker, Cate Blanchett, John Rhys-Davies, Bernard Hill, Billy Boyd, Dominic Monaghan, Orlando Bloom, Hugo Weaving, Miranda Otto, David Wenham, Karl Urban, John Noble, Andy Serkis, Ian Holm, Marton Csokas, Lawrence Makoare, Thomas Robins.

Synopsis: Gandalf and Aragorn lead the World of Men against Sauron’s army to draw his gaze from Frodo and Sam as they approach Mount Doom with the One Ring.

***********

By the time Peter Jackson’s film version of The Return Of The King was due to hit cinemas across the world in 2003, most people were either confident in the director’s skill to bring the story of Frodo, Sam and Gollum to a satisfactory conclusion, or terrified he’d stumble at the final hurdle. The two previous entries in the Lord of The Rings film trilogy, Fellowship of The Ring and The Two Towers, had been massive commercial and critical successes. Most people wanted the trilogy to work: however, the Hollywood law of diminishing returns meant that, technically, sequels of successful films generally made less money, and were not as good as, the film they spawned from.

That said, people needn’t have worried. When Return Of The King was unleashed upon the world in December of 2003, all fears proved unfounded. Jackson’s (or ours, depending on how you look at it) luck had held firm. Return Of The King was an unparalleled success.

With the first two films of the trilogy safely tucked away, with both Theatrical and Extended DVD editions available to the public, Jackson’s full focus was now on bringing the gargantuan story to a satisfying climax, and emotional resolution. With Frodo and Sam, along with Gollum, still to traverse the despairing wastelands of Mordor, to the steep slopes of Mount Doom, you got the feeling that the film had a fair amount of material to cover.

Broadening The Story

Conversely to Tolkien’s original story, Return Of The King the film was the longest of the three in the series. Clocking in at nearly 3 and a half hours, it’s a monster; both in terms of storytelling power and narrative excitement. The novel, in it’s original form, is barely half, if not a third, the length of series originator Fellowship. When reading Return Of The King, it’s clear to see that Tolkien’s initial love of long exposition within the text body had waned a little, perhaps as the story sped up, he felt the need to compress his writing. The published novel of Return is almost able to be divided in half again, the first part being the body text, the second being the Appendices, the vast supply of information and back-story to a lot of what occurs in The Hobbit and The Lord of The Rings. Was Tolkien “rushing” his final book? Was he pressed for time, and forced to condense the final act of his work into a story that was limited and mediocre by comparison to what had come before?

Tolkien was initially reticent to publish his work, The Lord Of The Rings, in three separate volumes. He figured that since it was all one piece of literature, it should therefore be published as one piece of literature. It’s commonly known now that his publisher was able to convince the author that to publish all three parts in one collective volume would be both prohibitively expensive, and almost impossible to market (since the page count was inordinately high) so the story was broken up into the three novels we’ve come to know today, Fellowship Of The Ring, The Two Towers, and the final chapter, The Return Of The King.

With Fellowship, Tolkein spent a great deal of time setting up the world, the characters, and the idea of the Ring and Sauron, and what had to be done. His passion for this world is evident in almost every line and paragraph, the detail with which he scribes his ideas is staggeringly exquisite. The journey from the Shire to the sundering of the Fellowship on the shores of the Rauros takes place over many pages, and The Two Towers, while substantially compressed for detail, posits a large quantity of information in a short literary work, relatively speaking. The Battle for Helms Deep, for instance, takes only a chapter of The Two Towers, however the film version last almost half the movie. With Return Of The King, however, everything goes pear-shaped quite quickly. The carefully constructed world and language Tolkien had developed is given short thrift in the novel, instead allowing the War of the Ring to come to a head, be fought, and won or lost in a few pages. The battle at Minas Tirith, on the plains of the Pelennor Fields, is described in the book in rather brusque detail, for Tolkien. Tolkien appears to blanch from the intricacies of detail he used in previous instalments, instead seeming to want to paint sweeping vistas with large scale carnage and action in it’s place.

Whereas before you could almost smell the forest and trees of Lothlorien and hear the whistle of arrows in Helm’s Deep, in the literary version of Return you merely get a sense of it all, almost as if the detail is lost as the reader tries to look in multiple directions at once. It must be noted, I feel, that it would appear that Tolkiens’ language in Return Of The King is surprisingly elegiac, a mournful dread hangs across proceedings, as it must, I guess, when times are darkest. Tolkien writes Return almost as a poem, a kind of lamentation to horror unfolding and lives lost, as if he’s painfully aware of the agony Middle Earth is enduring as the forces of evil sweep the land. As such, the fine detail accounts so brilliantly written in Fellowship are somewhat less so conspicuous here, instead the broad brushstrokes of a writer trying to accommodate the bulky, weighty story he so accurately developed until this point into a cohesive, understandable narrative. To me, and this is just my opinion, Tolkien appeared to want readers to be less inclined to follow individual stories and more interested in the world-view aspect, the birds-eye look down as God would upon the landscape, assessing all aspects virtually simultaneously.

Jackson and his writing partners, Philipa Boyens and Fran Walsh, expanded and structurally deviated from the written word of Tolkien, continuing the moulding and manipulation of time and place within the context of their established film format. The Battle of Pelennor Fields, and the War Of The Ring, take up almost two thirds of the film. Intercutting that with Frodo and Sam journeying up the mountainside and though the brimstone-wracked landscape of Mordor, the political machinations of Rohan, and Aragorns internal struggle to accept that he is destined to become King of Gondor, and Return Of The King becomes a film bogged down with so many plot developments and character storylines, it’s amazing the whole thing doesn’t collapse under it’s own weight. What is great about Return, and about the previous films as well, is that they are essentially ensemble pieces, and so the audience now expects to be following multiple stories and characters. The audience is willing to follow the characters we’ve grown to love over the years as they now struggle through their darkest moments. Except for Gimli and Legolas, whom again become the light-hearted humour in the film.

The problem with ensemble films generally is that somebody, somewhere, gets short thrift in terms of character arc: as with Fellowship and Towers, Return manages to shoehorn everybody’s character into the film and still give you a decent development of each one. And aren’t there a plethora of characters!

Frodo and Sam, and Gollum in his own way, required the most massaging from Jackson and his writers for their character development, as the journey to destroy the Ring is the key part of the film, and the whole purpose for the story in any case. Frodo’s descent into madness, his resurrection from despair and emotional obliteration is one of the film’s strongest points, analogous to the despair we all feel at times during our lives, when things seem darkest, and there’s no way forward. His light, his touchstone of hope, you might say, is Sam, whom carries Frodo when all seems lost. Figuratively, and literally, Sam is the real hero of Return, moreso than the Rohan warriors riding into the swollen armies of Sauron, moreso than Eowyn standing to face the Witch King of Angmar on her own, sword in hand. Moreso even than Aragorn turning, anguish on his face as he thinks Frodo is dead at the last, and despairingly imploring his troops to charge against the gates of Mordor in a last effort to defeat evil. Sam is perhaps the bravest soul in Middle Earth, not for any physical ability, not in the least. For his courage to lift his friend up when he falls, to take the burden that is slowly killing Frodo and assume it himself; not out of jealousy or anger, but because he knows that he’s the only one who can.

Frodo, weakened by the power and influence of the Ring, is unable to bear the burden any further, as they lie, soot-stained and exhausted, on the side of Orodruin, being Mount Doom. His gasping, raspy voice quavers as he seeks faith from Sam, pleading with him to justify this madness, this journey, and why they must continue. Frodo is wrecked beyond accounting, his body scarred and battered from his burden, his fight with Gollum and his battle with Shelob. It is when Frodo is at his weakest, both in body and mind, that Sam steps up. Jackson and Walsh, along with Boyens, have delivered a hero unlike any we’ve seen before on screen: a hero who isn’t the main character. Ultimately, Frodo is unable to finish his task. His resolve is so weakened by the time he stands above the fires of Mount Doom, on the precipice looking down into the lava, he cannot abandon the Ring. It is a mirror upon the same resolve of Bilbo, who was threatened with obliteration by Gandalf in order to give up the Ring’s power. Both Bilbo and Frodo, members of the same family, are ultimately both unable to do what must be done, alone. They require help, and in Sam, Frodo has his strength.

Gollum, meanwhile, continues on his own pathetic, sad journey. It’s not the character itself which is sad, or even pathetic, but when one realises the level of despair and loneliness Smeagol/Gollum has experienced through life, he almost becomes a sympathetic character. He’s not driven by a list for power (at least, not as told on-screen – in the book, Gollum wants the Ring for himself so he can continue killing and scheming in the depths of the mountain) so we attach ourselves as viewer to his plight in that he’s simply a beast of instinct. Gollum’s overriding schizophrenia is simply awful, you can see the twitches and quivers of his resolve and motivations as his Smeagol (good) side internally wars with his Gollum (bad) side throughout the film. It’s Jackson’s handling of Gollum that turns him from being simply a good director, to being a great one. The script allows us to feel Gollums torment, his anguish, the desire unlike any other to claim the object of his position in life: without the Ring, Gollum feels empty, unable to be himself. Perhaps the greatest pity of Gollum is that the Ring is the thing that caused him to become who he is in the first place, and it’s here the sympathy of the audience is generated. In the back of our mind, all the while, is the fact that at one point, Gollum was just like you or I.

A normal, sensible person, who is overcome with lust for an object capable of giving him power that he was deprived of in his early life. The power to become invisible, while certainly never expanded upon in the films at all (all we see is the alternate-world view experienced by Frodo in Fellowship) is a juicy, divisive element within Tolkien’s landscape. Tolkein saw that particular power as perhaps a way of dealing with his own problems at the time: after all, if one could simply vanish, would that mean one’s problems did too? In a world wrecked by war, Tolkien must surely have wished himself invisible, perhaps he was unable to come to grips with the death and destruction around him, and he sought escape in his literary works: inside of which he felt somebody had to feel as he did. Gollum’s journey in Return, which began so brilliantly in Towers, is again magnificent. His is a character with depth; in almost any other film, he would have been a one-dimensional character lacking in emotional depth and merely a cipher for the Hero to do his thing.

Aragorn, to my mind, is perhaps the least accessible of the characters in Return Of The King. His journey began so well with Arwen back in Fellowship, and he became a leader in Towers when he battled at Helm’s Deep, however, he appears to lose his way in Return. Suddenly, Aragorn is beset with fear as to his heritage, his lineage telling him one thing and yet his heart saying another. He needs more convincing, apparently, and doesn’t relish the idea of ruling over an entire country. One might say this is a decent quality: the best rulers are those who do not seek to rule, who will govern fairly without prejudice or favour, however the more cynical might say that the best rulers are those who want to rule, for the pride and valour in leading people through tough times and good will bring out your best qualities. To me, however, I see Aragorns’ journey through Return as a little wayward, a little out of character.

Aragorn never struck me as a character who would sit and think about things for too long, being all indecisive. His character always appeared in control and above conflict, he knew what to do every step of the way, made decision quickly and resolved a situation with little fuss. Perhaps, then, he needed to be indecisive, needed to feel insecure in his decision making to grow as a character. Like Frodo, Aragorn takes a little prodding from a good friend (in this case, Elrond, who returns the remade Sword Of Elendil to him) to sort himself out. But on screen, it’s not convincing. It’s almost like Jackson and Co didn’t quite know how to handle this part of the story, so they made Aragorn a little angsty, a little teen-rebellion all of a sudden. He kicks all manner of ass in Helms Deep, and then starts to doubt himself? Who is he kidding? Still, his storyline in the final act of the film, where he leads an army across the plains to confront the armies of Mordor streaming from the Black Gates, is powerful, genuinely emotional stuff. He loses his way a little in the middle of the film, but gets back on the horse at the end.

The character development of the other Hobbits, Merry and Pippin, is a substantial bonus for the film. In the novel, they’re underused and only really mentioned as ancillary members of the story at the point Return kicks into gear. In Jackson’s version, he expands their stories into a more rounded, well developed and natural way.

Merry, who returns to Rohan with Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli, befriends Eowyn, the niece of Theoden. When called into battle, Merry wants to take part, however Theoden requests he stay behind, as he see’s Merry more as a liability. Merry, pouting slightly, utters one of the film’s best lines: in which he describes himself as an inhabitant of Middle Earth as well, and wonders what will happen to the Shire should Sauron defeat the armies of Men. It’s a far cry from the Merry of Fellowship, more in tune with stealing carrots and potatoes and cooking up mushrooms. As the tone of the film becomes more and more grave, we see less of Merry’s natural humour, and more of his serious side: a sense of honour and faithfulness to the cause that we had ne’er before seen in the young Hobbit. He refuses to bend to Theoden’s will, and, with a disguised Eowyn carrying him on her horse, he joins the Battle of Pelennor Fields and finds his courage. The idea of self sacrifice, embodies in a variety of ways through every character in the film, is one Tolkien espouses greatly within Lord Of The Rings, due in no small part to the “for the greater good” mentality during the World War’s that plagued the Earth in the early half of the 20th century. One man’s sacrifice might very well save hundreds of others, so no thought was given (at the time) to one’s own life, instead, in the defiance of evil, you became part of the mob, part of the whole, like a wave of humanity sweeping onto the beach of War, erasing the footsteps of tyranny in the sand before you. Here, in Merry, we see a similar sentiment, in that he wants to fight, even against incalculable odds, an almost unwinnable battle in a land that isn’t his own. Sounds awfully familiar, I think.

Pippin, almost parallel to Merry, develops as a character as well. While he may not become involved with the Battle directly, he does so in an indirect fashion, as he hides in Minas Tirith to draw Sauron in that direction, whilst Frodo and Sam continue their quest from another. Pippin becomes the Poker Face of the War, Sauron’s focus is on him when it should be elsewhere. Pippin, while also a joker at the start of the story (with his resolve hinted at during a frightening moment in Fellowship where the Black Riders almost catch Frodo with the Ring… “Buckleberry Ferry? Right, follow me!” he says, his eyes set.) develops into an emotional, pragmatic and almost egalitarian soul, who learns (painfully) that the world is not all green grass and mushrooms. The script allows Pippin to learn these lessons through both the actions of Gandalf and Denthor, the former being the kind and wise wizard who take Pippin under his wing, and the latter a bitter, mentally destroyed old man bent on conforming the world to his own will, not accepting that things are changing.

Perhaps the other key character in the film who requires a little prose is Eowyn, the younger niece of Theoden, King of Rohan. Eowyn represents the feminist movement in Middle Earth, her character buffeting against the tide of male dominated affairs with her people; women of Rohan are not allowed to fight, something she opposes quite strenuously, although Theoden forbids it. Regardless, when the fight begins, Eowyn joins the battle, and eventually strikes a decisive victory against the armies of Mordor, as she slays the Witch King of Angmar in hand-to-hand combat. Her moment, her shining light in the battle, is a moment in the film which will make you punch the air with a “that’s the way!” cry. Eowyn, played wonderfully by Miranda Otto, is one of the major players of this film, although I feel her part is slightly underdone by Jackson in terms of emotional content. Her scenes with Merry, as she carries him to war and stands by his side as they fight Orcs on the ground, are particularly powerful, however I think Jackson short-changed the character a little in his initial cut. The Extended version, all of which will be explored further in a separate article, expands her role somewhat, although only marginally.

Jackson and Co managed to expand the characters from the written page of Tolkien’s text into people with depth, a sense of purpose and logic behind them. By delving into the appendices, and taking anecdotal and ancillary material from other texts the author wrote over his lifetime, Jackson was able to find more detail about the characters that weren’t immediately apparent in the body text of Return. The expansion of Denethor, for one, was an element that I felt was overdue, however, the handling of this part of the story was a little off-key. Denethor is a complex character, for sure. His inability to handle the death of favourite son Boromir is the catalyst for the lack of preparation (and Gandalf’s subsequent subversion of his troops) for the approaching War. His mind is broken, and I can see how Jackson has tried to portray that on screen: for me, though, it rings a little hollow. Perhaps its the slightly garrulous acting style of John Noble, who seems for all the world a little lost in his characters oblivious mumblings, but I just felt that Denethor’s role, and the way it was handled by Jackson, wasn’t as well rounded as it perhaps could (or should) have been. But, at least they tried. It’s a testament to Jackson that any of this worked at all, let alone a single failing in the character department make this film fail miserably. One of the advantages of an ensemble film is that if one character is shallow or undeveloped, there are others to pick up the slack. Of course, that being said, it could also be conversely construed that if one of an ensemble fails, then it drags the rest down too. Thankfully, this did not happen in Return.

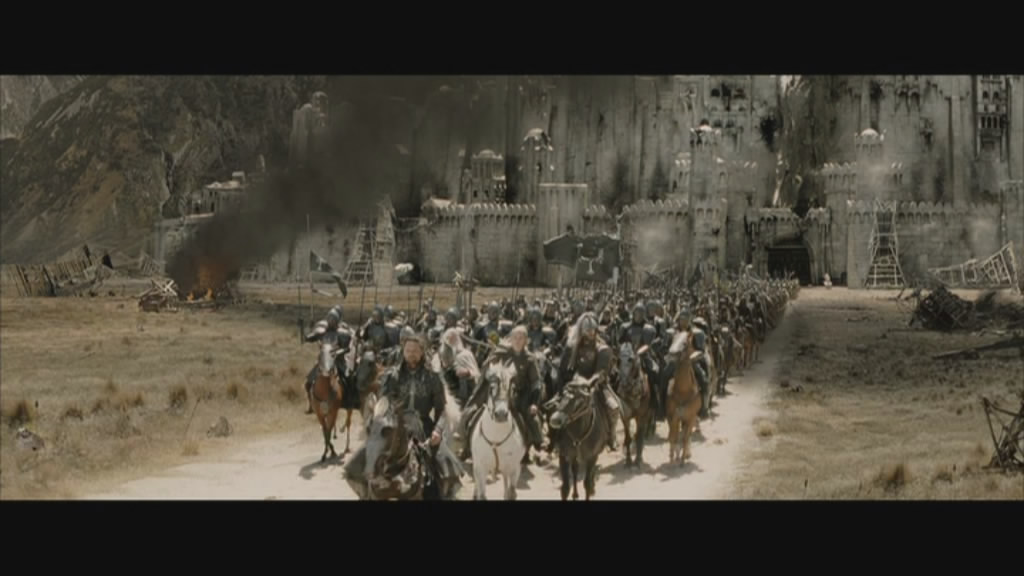

The final battle at Pelennor Fields, before the walls of Minas Tirith, is expanded substantially by Jackson from the original text. While mention is made of almost every element on screen within the original text, Jackson has taken that mention and created entire sequences out of them. Case in point: the mumakil. The giant elephant creatures, or mumak’s in Tolkien’s language, advance upon the armies of Rohan who have taken the field on horseback, stomping and sweeping aside all who get in their way. In Tolkien’s original text, they are mentioned as follows:

“And now the fighting waxed furious on the fields of the Pelennor; and the din of arms rose upon high, with the crying of men and the neighing of horses. Horns were blown and trumpets braying, and the mumakil were bellowing as they were goaded to war……..”

“…….But wherever the mumakil came there the horses would not go, but blenched and swerved away: and the great monsters were unfought, and stood like towers of defiance, and the Haradrim rallied around them…..”

“……and both Duilin of Morthond and his brother were trampled to death as they assailed the mumakil, leading their bowmen close to shoot at the eyes of the monsters.”

Such was the limit to which the Mumakil entered the battle, and it was something to which Jackson felt aggrieved, perhaps. The charge of the Mumakil in Return Of The King, and the subsequent battle in the immediate aftermath of that charge, is akin to nothing you’ve ever seen on screen before, or even since. It’s ferocity is only outmatched by the calm with which Jackson directs the event, his camera lurking around the feet of the giant beasts as they stomp their victims into oblivion. Jackson even instigates a moment with Legolas, where he single-handedly brings one of the giant creatures down, a moment of partial comedy and “Legolas is one mo-fo you don’t want to mess with” heroism that, in it’s inherent value, almost mitigates the lives lost by those brave soul who ventured out to battle the beasts and perished: the Riders Of Rohan lost large numbers of their own in order to bring even one of the beasts to it’s knees. Still, for the greater good, they say. Little tips of the hat like that, while initially quite cool, resound with a definite un-Tolkien-like bravado that almost strikes against the heart of the film.

Still, it’s a colossal effort from Jackson to create a story out of what could have been an utter mess of a narrative: with so many characters and events all clamouring for screen time, a less hardy director would have been reduced to a blithering wreck.

Telling The Story

Return picks up almost immediately where The Two Towers left off. Gandalf, Aragorn, Gimli and Legolas, along with assorted members of the Rohan force from Helms Deep, journey to the Tower Of Orthanc, where a defeated Saruman has holed himself up, guarded by Treebeard. There, they come across Merry and Pippin, both safe after their adventures in The Two Towers, and smoking pipeweed. Meanwhile, Frodo, Sam and Gollum have continued their journey towards Mordor, with the deceitful Gollum planning his revenge upion Sam and the taking of the One Ring. In Return of The King, we see a flashback at first, prior to current events, in just how Gollum was “born”. A young hobbit-like creature, known as Smeagol (and hinted at by Gandalf in Fellowship) see’s his brother Deagol find the Ring at the bottom of a river, whilst they are fishing. Jealous and consumed with desire to have the Ring for himself, Smeagol kills Deagol, and takes the Ring from his brothers dead hand. Smeagol, now outcast from his family and friends, hides up in the mountains, in the deep darkness, away from prying eyes who might otherwise want the Ring as their own. The long, sad history of the Ring continues, as we know Gollum eventually loses the Ring to Bilbo (as seen in the opening monologue of Fellowship) after a long period of darkness.

This flashback, fronting the film, segues into the story proper, as we rejoin our various cast members on their respective journeys. Gollum leads Sam and Frodo on a perilous journey close to an enemy stronghold, Minus Morgul, to a stairway leading almost vertically up and over the mountains into Mordor. However, the scheming ratbag knows of a hidden danger in the cave system at the roof of the mountaintops, Shelob, the giant spider. There, he plans to dispose of Sam and Frodo by allowing Shelob to eat them, and then he plans to steal the Ring back for himself. However, the friction between Frodo and Sam over the fate and trustworthiness of Gollum leads to a falling out, with Frodo sending Sam packing, in one of the film’s most heart-wrenching scenes (among many, many others).

Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli return to Rohan with Theoden, the King of The Golden Hall, to await Gandalf’s word of things in Minas Tirith, the capital of Gondor, the most powerful of nations. There, we find an utterly insane and paranoid Denethor, intent on refusing to acknowledge that Sauron’s forces are mounting, and that outright War is coming to Middle Earth. Denthor, who is the father to both Boromir from Fellowship, and Faramir in The Two Towers, plays a pivotal role in emasculating his son Faramir, whom he see’s as a failure and not worthy of the family name. Denethor is utterly mad, by now, the loss of Boromir in Fellowship coming as such a blow it’s driven him insane with anguish. Which is a concern, given that Denethor is guardian of the throne of Gondor, to which Aragorn can rightfully claim…… a claim that Denethor denies vehemently. Gandalf see’s in Denethor the utter madness that will ultimately claim his life, however, sine Denethor is the ruler of Gondor in the King’s absence, he must acquiesce to his laws. Pippin, whom Sauron thinks has the Ring and thus is taken to Minas Tirith by Gandalf for safekeeping, binds himself to Denethor with an oath of allegiance in a moment of regret over the death of Boromir, and Denethor accepts it. Soon, however, the forces of Mordor will approach, and Gandalf knows he must take more decisive action.

Meanwhile, across Middle Earth and in the hall of the King of Rohan, Aragorn must somehow persuade Theoden to commit his forces to battle when War begins, lest the future of man, elves and dwarves (and, we cannot forget, the Hobbits) be swept asunder by Sauron and his battalions into an era of darkness and despair. Theoden, bitter that Gondor’s forces did not attend Rohan in it’s hour of need at Helm’s Deep, is reluctant to do so, however, the prospect of a cataclysmic annihilation doesn’t sit well with him, and eventually he comes around to fight.

Frodo, his mind slowly being crushed under the weight and influence of the Ring, finds himself increasingly angry and desperate within himself and his mission to continue, that he lashes out at those dearest to him: in this case, his best friend Sam. Adding to this pressure, is the slimy weasley insinuations of Gollum to turn him against Sam, something that Frodo eventually does in a moment of madness (referred to above). However, Sam is a better person than that, and can see that it’s not Frodo talking, but the Ring. And Sam knows, just knows, that Gollum is a traitorous deviant to the last, desperate only for one thing; attaining the Ring. When Gollum leads Frodo to Shelob, and Frodo is captured by the giant spider after a fierce fight, it is Sam who comes to his rescue. It is Sam who defends his masters’ honour in the darkest hour. However, Sam must carry the Ring for a time, as Frodo is taken to a dark tower by some nasty Orcs, whom seem intent on both eating Frodo and returning the Ring to Sauron…. or perhaps even keeping the Ring for themselves. Jackson captures the desperation of the situation well: all dark, shadowy, creepy, evil and dank, wet slurry-filled despair reeks from the screen as Shelob skulks about her cave, preying on her hapless victims with her poisonous spike.

Jackson manages to intercut the story in places that create a sense of “oh wait a minute, what’s going to happen next?” in the viewer, almost like soap-opera cliffhangers at the end of a season. The battle of Pelennor, ripe with potential to become a Saving Pirvate Ryan shemozzle of bodies, limbs and blood, is actually a relatively gore-free affair, except where absolutely required. People get stomped, crushed, sliced, slewn, hacked, chopped and mowed down by horses, mumakil and the Nazgul in this epic, revolutionary setpiece, which will unlikely be topped in modern cinema during our lifetime. Not only is this true cinematic spectacle of the highest order, this is simply a filmmaker showing up just how damn awesome Tolkiens’ world can actually be. Minas Tirith, its crested walls and battlements glimmering white against the black clouds forming around Mordor and the advancing army, is a beacon of man’s last hope against tyranny, against evil. The sheer scale of the battle is something even the most competent director would have thought twice about: but still, if you’re going to make a film with a ginormous battle sequence squarely in the centre, you might as well go all out.

The bombast of battle is often countered with the more subtle, character driven moments, which the audience is thankful for, since the conflagration of Middle Earths finest in combat is often too much to witness, and must be divided with moments of relative peace. Frodo and Sam, staggering through Mordor and up a steep mountain (with lava inside and all around, no less!) are also in a fine pickle, however, theirs is more dialogue and character than any true action. It’s a refreshing change to cut to them for a few moments of heartbreaking emotional content. And indeed, their eloquent, and often desperate, dialogue is the film’s key pivot; it’s this reason that the forces of evil are fighting for, so this is important stuff. And Jackson makes it work. He refuses to engage in rapid-fire editing, he’s confident enough of the performances and scripting to allow the story to tell itself without help. There’s a languidity, a relaxed sense of occasion, that accompanies Jackson’s work on Return Of The King, a sort of refusal to bend and buckle under the narrative pressure by Jackson to simply cut stuff to reduce the film’s runtime. The film is long, to be sure, but it’s required to be so, simply because the story demands it.

One of the most critically questioned parts of the film is the ending – or rather, the multiple ending’s Jackson employs. A full twenty minutes after the Ring and Gollum end up in the lava of Mount Doom, and our two small Hobbits escape certain death by millimetres, the film is still going, winding up all the loose ends and plot developments. Frodo and Sam are saved from Mordor by Gandalf, there’s the obligatory reuniting with old friends, the coronation of Aragorn as King Of Gondor, and the return of the Hobbits to the Shire, which appears for all the world that it never even knew of the War of The Ring. While many critics regard this multiple endings’ sequence as fanciful and unnecessary, if you step back and look at the film as a conclusion of a trilogy rather than a film on it’s own, you’d see that the concluding moments of the film are actually required. While the Scouring Of The Shire chapter (of the original text) was excised from the script for the sake of it being somewhat anticlimactic for a film, Jackson has crafted a worthy, and emotional heartbeat for the film to bow out on. The end of twelve-plus hours of film cannot simply be concluded with a single, lingering sequence wrapping things up neatly. The Ring has been destroyed, fair enough, but we need to see just how the story has affected our characters. Frodo is a ghost of his former self, more mature and wiser, yet somehow empty of the light he had within himself at the beginning of Fellowship. The return to the Shire, which is filled with elation for our heroes, is tinged with a melancholy that they won’t be the same again. Like They say, you can never go home again. And the same is true here. Frodo and Bilbo, together with Gandalf, leave the shores of Middle Earth with the last of the Elves, never to return. When I first read Lord Of The Rings, I took the Grey Havens to be some sort of representation of an ascent into Heaven.

Now I know that it’s simply people leaving Middle Earth on a boat, sailing out in search of white shores, and a far green country under a swift sunrise.

Stunning Digital Effects: How To Tell a Story Via a Computer

With the development of computer software able to handle the intricacies of planning and executing large scale battle sequences, with digital characters on screen, all interacting and bouncing off one another, WETA Digital had one of the most formidable weapons in it’s arsenal to deploying Peter Jackson’s ideas into the film. The Return Of The King, perhaps the single most ambitious film made since Ben Hur or Cleopatra, relied heavily on the use of the MASSIVE computer programme. Essentially, MASSIVE allowed the filmmakers to take a single digital entity, say, an Orc or a Rohan soldier, and place him into a virtual world of their choosing. Then, using a sophisticated artificial intelligence generator, make that digital entity interact with said environment: in the case of Return, make that soldier or Orc warrior fight with another. This gave the filmmakers so much freedom to create massive, panoramic vista’s of battling creatures, that it freed up the CGI boys for the rest of the film’s staggering effects. MASSIVE managed to do what all of George Lucas’ digital lads couldn’t in those abominable Star Wars prequels: help tell the story well.

In Return Of The King, and for that matter, the other two films as well, Jackson’s vision relied heavily on a large quantity of special effects. From the simple effects like the differing sizes of our characters, to the large scale epic ones like the Pelennor battle, with hundreds of elements to incorporate, it would be easy for the audience to become lost or jaded to the fact that computers were used in the creation of these films. It goes without saying that most films these days have some kind of computer enhancement, or even CGI, in them. Even the most staid drama can have elements of it that contain a computers’ vast binary power. In most cases, the filmmaker seems to think that if they use that shot as a “hey look at us and how much money we spent to make this shot” moment, which pulls the audience out of the film and back into the cinema.

I have to say, I’m going to use the George Lucas school of thought here, to emphasise my point and to make it clear just how brilliant Jackson’s use of technology was in The Lord Of The Rings.

George Lucas, in his revision of the Star Wars Original Trilogy in 1997, went in and added a whole slew of digital creatures and additions that in no way served the story, or assisted in telling the story. Additional background characters, robots, a bizarre dance sequence in Return of The Jedi, all added up to somebody who had the power do do this stuff, but no idea how to integrate it into a story well. And when Lucas started his Prequel Trilogy, starting with The Phantom Menace, we knew film-making as an art form was lost to him. Lucas’ predisposition to doing things digitally had a negative effect on his stories. His prequel films served not as an addition to Star Wars canon, but merely as a platform for how cool his special effects team could make things look. Flashy, derivative effects over a wafer thin, undercooked storyline, made the Prequel Trilogy instalments the laughing stock of fans of the series across the world, and highlighted just how poor a storyteller Lucas really was. He might have some great ideas, but he couldn’t create any sense of excitement (even the second and third Star Wars films were more exciting than the original, because Lucas wasn’t directing them!) or understand character development at all. Now, I know I sound like I’m bashing George Lucas here, but well, he started it. The Phantom Menace, shot almost entirely on green-screen save a few moments in the desert, and featuring one of the worlds worst all-digital CGI characters in Jar Jar Binks, managed to serve up to the world a steaming pile of crud unlike any we’d seen in years. The flavour of the original Star Wars films had been diluted in a blazing stream of digital tomfoolery that was never going to be able to enhance the storyline at all.

Unlike Lucas, Jackson recognised in CGI and computer effects the ability to enhance his story, help him tell it, rather than be the story itself. Too many effects films rely on the effects for the story, rather than the story for the effects, and with Jackson, he ran the risk of falling foul of the same idea. Instead, Jackson spent more time developing his script, developing his characters, and designing them realistically, so that when people saw them on screen, it wouldn’t matter whether they were a puppet, a digital creature, or a man in a suit: you’d buy into it and believe it was real.

Gollum, particularly, was a stand-out of Jackson’s. When people first heard that Gollum was going to be an all-CGI character, flashbacks of Jar Jar Binks and the horror that surrounded him came flooding back. But the proof, you see, was in the pudding. WETA, plus Andy Serkis, plus a great script, meant that Gollum as a CGI creation would have more texture and layering as a character than the all the combined might of a Star Wars Prequel trilogy together. The Nazgul, winged riders of Mordor, the charge of the Rohirrim, the mumakil, the ascent to Mount Doom, Shelob and the armies of darkness: all were created using the power of a computer, however the key with their success, and Jar Jar’s failure, is that they were characters first, and digital creations second.

Jackson knew where to put the effects in. His reliance upon computers to serve the story, rather than enslaven him to it, was key. And to his credit, Jackson achieved more in a single hour of Return Of The King than Lucas could in 3 Star Wars films.

The End Of All Things

“It’s a clean sweep: the winner, the Lord Of The Rings: Return Of The King”. – Steven Spielberg, 76th Academy Awards.

When Return opened to rave reviews and a critical acclaim unlike almost any film before or since, you felt something special was in the air. Peter Jackson had accomplished something nobody had attempted before: to tell the story of Tolkien’s world with live action, successfully, making money along the way. And fans across the world breathed a collective sigh of relief. The pressure and hype surrounding Return Of The King had been enormous, although if you asked Jackson, he’d smile and say that everything was under control.

It was a hype that continued until the Academy Awards, where Return was nominated for 11 Oscars. It won all eleven, forever standing next to Titanic and Ben Hur as the most awarded films of all time. Return still holds the record as the second highest money-making film of all time, behind Titanic, a feat that is unlikely to be broken save the release of the forthcoming Hobbit film.

It’s unlikely that Tolkien would have appreciated all the attention Jackson’s films received, all the hype and publicity; I would suggest that perhaps Tolkien himself might have smiled a little, but be more rewarded with the acceptance of his story onto a stage unlike any he’d been able to envision while he was alive. The legion of fans of the story, both novel and film, will only grow over time, as more and more people encounter these films on DVD, BluRay or even TV. This is what Tolkien would have preferred, I think, no matter the medium, no matter the cultural barriers of distance and politics.

With Return Of The King, Jackson vindicated Bob Shaye’s assertion that the story required three films, and gave Hollywood a quality of film-making that perhaps would never again be equalled.