Movie Review – A Tale Of Two Titanic

The title of this article is wrong. I got to thinking about the Titanics I had seen on film, and I realized there were at least four of them that have featured in semi- (or pseudo-) historical cinematic retellings of the tragic events of April 14-15, 1912. (This is not counting Titanic cameos: Time Bandits, Raise the Titanic!, and recent goings-on on Doctor Who.) So the awful pun that popped into my mind when said mind contained but two Titanics (James Cameron’s and the Titanic lionized in today’s rant, the Titanic of A Night to Remember: Hello, Bi-tanic!) morphed into Tri-tanic when I recalled Germany’s early Nazi-era go at the story (S.O.S. Titanic, essentially a diatribe against the shortcomings of capitalism: a very odd film, to say the least), and finally hit the shoals of nonsense and sank when I remembered the Titanic of 1953, starring Barbara Stanwyck, as a four-way Titanic pileup, or, of course Quar-tanic.

Or not. For the sake of sanity and linguistic safety, we’ll be concentrating on two Titanics, those of Mr. Cameron and British director Roy Ward Baker. (First, though, a parenthetical in honor of the Barbara Stanwyck one: 1953’s Titanic is by far the hammiest of the lot. Add to a viewing two slices of bread, lettuce, tomato, and mayonnaise, and you’d have yourself a fine sandwich. It shares with Cameron’s Titanic a compulsion to drop “original” characters into the account– heaven knows, having only twenty-two hundred people on the ship has limited Titanic-tale scriptwriters in terms of drumming up interesting personal stories; here, Miss Stanwyck is in the midst of a bitter divorce from tight-lipped Clifton Webb while son Robert Wagner, at that point in his young life the dictionary definition of “callow” [with Fabian hair], is caught in the middle. Never mind that we’re stuck on a sinking ship some three hundred miles from the nearest land; Stanwyck et al. have BATTLES to fight. Adding to the fun is the fact that Webb’s character is a minister who leads the doomed passengers in singing hymns with a verve and at a volume that would have the Mormon Tabernacle Choir slinking away in shame. I remember thinking, witnessing the sheer indulgent Spamburgerness of it, The only way they could make this better is if something BLEW UP. And then something did blow up! The filmmakers, perhaps having in mind one too many World War II spectacles like Action in the North Atlantic, decided that one of the boilers just had to go– historical accuracy be damned. And Doug here, I must admit, crowed with joy.)

Watching Titanic, and then, umm, Titanic, I had to ask: What in the hell do we need these fake people for? In 1997, I sat in a theater watching Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet play drama-cute against the backdrop of the most famous naval tragedy in history, and I thought: You had two thousand real stories to pick from, Mr. Cameron; you couldn’t find anything of interest?

In short, with respect to things Titanic, composite characters I respect. Creations I don’t.

Arguably, I haven’t seen Titanic all the way through for some time. What I remember: the endless scene in which Kate Winslet, as Rose, threatens suicide from the fantail. (I refuse to believe I was the only one in the theater silently chanting “Jump, jump, jump, jump.”) Billy Zane twirling an invisible moustache, with John Warner’s help. Anachronistic feminism, with a capital EFF. The Struggle Between the Classes, also capped, written with all the subtlety of a forty-pound river sturgeon to the face. And some damned nonsense about a huge blue diamond.

Oh, and Kate Winslet’s breasts. (Which James Cameron, I understand, sketched for purposes of the film. I’ll say it if no one else will, Jim: creepy.) But, as that comment is apt to clash with the noting of capital-EFF-feminism, above, I am discreetly loath to make it.

Cameron also presented us with a framing device in the form of treasure seekers, led by Bill Paxton, who were after that big fictional blue diamond. They were, to say the least, a sneaky, nefarious lot. All we were missing, when everything was said and done, was a time-travelling Indiana Jones in a wetsuit flicking that diamond out of Billy Zane’s hand with his bullwhip and then handing the greedy Paxton a manly beatdown. Maybe they can add that to Titanic’s fifteen-year-anniversary edition.

The makers of A Night to Remember didn’t need blue diamonds, Bill Paxton, or Professor Jones. In the 1950s, re-emergent Titanic fever had yet to hit. Before Robert Ballard found the lost ship in 1985, before James Cameron himself bathysphered his way fourteen thousand feet into the waters of the Grand Banks to have a look at her rusticled hulk, Walter Lord in 1955 wrote the first detailed, documentary account of the sinking of the RMS Titanic. At that point in history, Lord still had fairly ready access to survivors of the sinking, if not to the Internet or computer simulations; he travelled the globe locating those survivors and listening to accounts. The result was a meticulously detailed book, if one biased, innocently enough, by the vagaries of memory, the distance of time. Lord’s story is far more generous, too, than Cameron’s account on film, especially with regard to the actions of the ship’s command staff. A Night to Remember, both as book and film, is respectful yet frank; where Cameron seems content to take cheap shots at the evils and shortsightedness of corporate stoogery as the ship goes down, A Night to Remember presents us with a full spectrum of human response: we see officers and representatives of the White Star Line responding to the impending tragedy with courage and resourcefulness, with quiet acceptance or anger, with cowardice and shame.

It’s this egalitarian quality, oddly enough, that makes the film A Night to Remember difficult to examine. Save for Kenneth More, whose Second Officer Charles Herbert Lightoller serves as our focal point in the story, the cast is simply listed alphabetically in the film, and we’re not told who plays whom. Some of the characters– such as Molly Brown and Benjamin Guggenheim– are actual; some are composites. (The Titanic’s chief baker is the best of the “real” ones, and his story is amazing– and bizarrely funny: Thinking that he, as one of the ship’s working-class crew, had no chance of getting himself into a lifeboat, Charles Joughin got himself quietly bombed on rye whiskey down in his cabin. Then, with the flooding reaching his cabin as the Titanic settled lower in the ocean, he put on a heavy winter coat and went up on deck. As it turned out, he survived. We see him in the film amidst the panic as those trapped aboard the Titanic climb toward the ship’s stern; he’s blissfully drunk, and he’s the only one walking upright on the steeply tipping deck.)

The story, for those only recently arrived on the planet, is simple. It transpires thusly: in April 1912, the Royal Mail Steamer Titanic, a liner of unprecedented size and luxury, sets out from Southampton, England, Cherbourg, France, and Queenstown, Ireland, on her maiden voyage to New York City. Three days out, she hits an iceberg. Her owners have fitted her according to outdated naval trade regulations; as a result, she can provide lifeboat space for only twelve hundred of the twenty-two hundred people she has on board. Just under three hours after striking the iceberg, she sinks, sending fifteen hundred people to their deaths in the icy North Atlantic.

As befits his source material, director Roy Ward Baker tells the story like a documentary, with a brisk but creeping sense of dread. But if the film has the pedigree of something you’d find on the History Channel, it has the heart of an action film. For sheer nailbiting drama, I rank it with my personal favourite modern actioner-at-sea, The Hunt for Red October, where director John McTiernan juggles the storytelling between a dozen different settings, most of them cramped and static, many of them shot to look like the impenetrable darkness of deep ocean water, and all of them populated by people spewing great mouthfuls of technobabble (in two languages, yet!), and manages not only to make the whole thing seem logical and effortless but parks your heart in your mouth in the bargain, too. No mean feat– especially when compared to our long current slide into the jittery land of videogame Steadicam, when it’s now often impossible to tell, in a fight between two combatants, on dry land and in full lighting, who is hitting whom. (Or, in the case of the car chase that opens the otherwise excellent latest James Bond film, Quantum of Solace, who is pursuing whom. A hint to modern action directors: If you refuse any longer to provide us with establishing shots, then, please, don’t make all of the cars BLACK. I know black is stylish and sinister, but if we’re to follow the action, then someone has to bite the bullet and pick a ride in blue, gray, or even red.)

Like McTiernan thirty years later, Baker deftly weaves character threads and multiple settings between the Titanic and the ships that did– and didn’t– come to her aid. An early establishing sequence takes us from a dance among the Titanic’s steerage passengers, to a procession of first-class passengers entering the gorgeous main dining room, to the hellish roar and heat of the engine room, to, finally, the tiny room where the ship’s wireless operators toil sending heaps of messages. Among these, as it turns out, is one message most fatally heaped: Baker comes in for a tight closeup on an ice warning, just before chief wireless operator John Phillips (an appropriately beleaguered Kenneth Griffith, who looks for all the world like a young Freddie Jones) carelessly slaps a stack of subsequent telegram requests down on top of it. In a wonderful, chilling touch, Baker’s camera keeps returning, silently, to the ice message as still other slips of paper obscure it.

Baker and editor Sidney Hayers pace the story with precision and mounting speed as the dying ship settles more and more deeply in the water, cutting between the Titanic, to the Carpathia, to the Californian, damned now as the ship that didn’t come to the rescue, despite being a mere ten miles away.

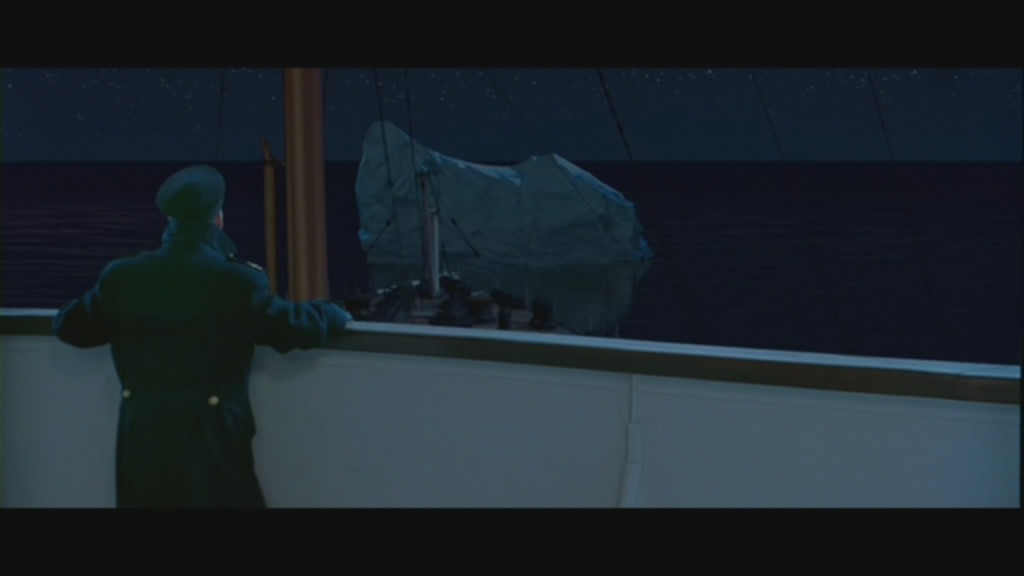

In the cast of A Night to Remember we find a who’s who of British film, though there’s nary a superstar in sight: a radiant young Honor Blackman as a wife and mother in First Class, a smooth-faced David McCallum playing Assistant Wireless Operator Harold Bride, Anthony Bushell as the heroic captain of the Carpathia. In Michael Goodliffe, who plays ship’s designer Thomas Andrews, we glimpse actual tragedy. We see it in his dark eyes, too intense, too sensitive: as if life mirrored art, he committed suicide in real life. Laurence Naismith, who plays Titanic’s Captain Edward John Smith, is the captain to visual exactitude; more importantly, he finds in Smith the understandable sorrow of a man who’s not only failed his ship and his passengers but whose final voyage as an oceangoing captain will end in his own death. (Smith was slated to retire after Titanic’s voyage to New York; one of A Night to Remember’s finest moments finds Naismith taking one last, silent look at the night sky before walking off into the abandoned wheelhouse moments before the ship sinks.)

Kenneth More, stoic but friendly Bertie Lightoller, is one of my favorite British actors. A mainstay of fifties British cinema, More here is the classic Everyman: a sort of early take on Anthony Hopkins, he’s burly, square-headed, handsome-homely, and intelligent. Not dashing: solid. Dependable. A bulldog on screen, a human Mini Cooper, squat and stable.

Like the rest of the film’s heroes, More’s Lightoller isn’t one, really. Not with Roy Ward Baker’s eye to detail and realism. Lightoller simply acts out of decency, discipline, training, and common sense. He’s a seasoned naval officer, as is Anthony Bushell, playing the captain of the Carpathia, the ship that comes to the Titanic’s assistance. At this point in history, that is to say the mid-1950s, I believe filmmakers could still safely make assumptions about their audiences’ knowledge of history and civics. Moviegoers knew something about Benjamin Guggenheim, John Jacob Astor, the “Unsinkable” Molly Brown. Now, to audiences whose attention spans are being dragged every which way by split-second spectacle and CNN-style newsbites, they must present history in childishly broad strokes; even in the fairly early Internet days of 1997, James Cameron managed to strip the equation in Titanic down to “poor equals ‘good,’ rich equals ‘bad.’”

This, unfortunately, left him little room for subtlety. By comparison, in A Night to Remember, the tragedy is much more contemplative. We have a moment of perfect, silent response from Michael Goodliffe when, right at the end, someone asks Andrews, standing alone before the fireplace in the Titanic’s First Class passenger lounge, “Aren’t you even going to try for it, sir–?” The band, of course, plays on while the lifeboats are loaded and lowered: so very quietly, discreetly, a simple civility so often lacking in modern film. The cellist softly sings “Nearer My God to Thee” while the other members of the band join in accompaniment, the sound of each instrument isolated and lonely even as they mesh in harmony. Baker doesn’t steer away from poignancy. “We should say a prayer,” says one of the boys from steerage, a young Irishman who’s been lucky enough to find his way into a lifeboat. Then, as the camera moves from boat to boat on the pitch-black sea, we hear the Lord’s Prayer in a dozen different languages. All the “class struggle” in the world is reduced to the sadness of common tragedy: something James Cameron, in Titanic, didn’t understand.

I don’t hide my love for A Night to Remember, or for what I see as its gift for heartbreaking understatement. (Maybe others in the modern audience see the film as too great an example of the classic cliché about the British and stiff upper lips.) I see John Merivale, as First Class passenger Robert Lucas, tenderly placing a necklace around his wife’s throat, then keeping his face cheerful as he bids farewell to her and their children on the boat deck. (With lifeboat space at a premium, women and children had first crack; husbands and fathers were left behind. Lucas has been told by Andrews how long the ship will live; “You and I may find ourselves in the same boat later,” he responds, drolly.) We and Lightoller are the only ones to witness Lucas whispering “Goodbye, my beloved son” to his little boy; I say only even though “we,” since 1958, when the film was released, may number in the millions; the moment is one of true intimacy.

Emotion clearly and honestly presented is a hallmark of the script. Take, for example, screenwriter Eric Ambler’s simple presentation of the fact that the ship is doomed:

“She’s going to sink, Captain,” says Andrews, calmly diagramming on a blueprint the damage to the ship’s hull.

“She can’t sink,” says a stunned Captain Smith. “She’s unsinkable!”

“She can’t float,” Andrews replies matter-of-factly.

A Night to Remember offers not only tragedy but class as a matter of course, not as an affront, and hence more believably (certainly less hamfistedly) than Cameron’s Titanic does. A definite, acknowledged class structure existed in 1912: it might be a hard fact to swallow for those of us dwelling in the uber-politically correct here-and-now, but as viewers of A Night to Remember we just need to stick our modern social sensibilities on the back burner and deal with it. The characters themselves deal with it: “Let’s go join in the fun!” says a well-dressed gentleman, as he and his lady friend watch a group of young men play an impromptu game of football (or soccer, to me and whatever American readers might be tuning in today) with chunks of ice on the deck below, well before the crew and passengers understand the tragedy that lies ahead. “But they’re steerage passengers,” his friend gently chides him. Elsewhere, a young newlywed couple on a stroll find themselves out of bounds, too. “We shouldn’t be here anyway. This is First Class,” says she. Chuckling in the cold, he pats her arm, draped over his: “They’re welcome to it on a night like this.”

Maybe it goes without saying, but Baker’s movie, though ambitious, hasn’t the technical advancements of Cameron’s story. Frankly, we don’t need them. (Though I will admit a wide-eyed thrill as the Titanic came to life, in color, in his film.)

We forgive the technical shortcomings of A Night to Remember (and, yes, they’re there: models that look too much like models, a matte-painting Titanic with the smoke from its stacks frozen against the night sky) on the basis of its overarching strengths. Three examples of utter subtlety: The frantic S.O.S. going silent as the second officer on the Carpathia, not understanding the new code for distress, shuts off the wireless. Water lapping softly on the floor of a cabin in Third Class. A hobby horse beginning to rock slowly, as if tipped by a ghostly hand, as the ship’s hull rips open, below the waterline, against the iceberg.

The film was shot primarily at England’s now-legendary Pinewood Studios, known most familiarly to modern filmgoers as the home of the James Bond movies. The main sets were built on giant gimbals that could be tilted as need be as the ship’s angle in the water increased. As a consequence, the sounds we hear in A Night to Remember as the Titanic sinks are chillingly real: the walls of the sets really were popping and creaking.

I remember, when Titanic came out, Cameron’s arguments in favor of the film’s artifice. Jack and Rose, Leo and Kate (if not Kate’s chest), that silly blue diamond: these things would lure a new, young audience to the film’s story, which, for the first time, would be presented with historical accuracy. Ballard had found the Titanic; experts had studied the wreck and formulated precise, scientific accounts of the sinking; Cameron himself had dropped nearly three miles down for a visit. He had personally shot film footage on location; moreover he had at his disposal all the bright new conclusions about the sinking, and the shiniest of those seemed to be that the people whom Walter Lord had interviewed in the 1950s were weak in their recollections. Modern science knocked heads with frail human memory; now, in the 1990s, memory lost. To put it bluntly, for the purposes of Cameron’s computer-enhanced film, those who had survived the sinking were wrong.

But fear, cold, and darkness can have a profound editorial effect on memory. And, in all fairness, “truth,” even as supplemented by silicon chips, is malleable. For Cameron’s take on the sinking of the RMS Titanic— so crassly presented in his film by an actor I remember only as a guy who looked like Harry Knowles of Ain’t It Cool News (was that Harry Knowles?) as he runs an animated simulation for octogenarian (or, if we believe Cameron’s screenplay, centenarian) Gloria Stuart, playing a much, much older Rose, about how the ship’s stern rose steeply into the air before breaking free of the ship itself (“That’s a whole lotta ass!” leers maybe-Harry, as the animated Titanic splits in two.)– has since been disproved, too. It all came down to the weakness of the rivets holding together the plates of the ship’s hull, if we’re to believe Brad Matsen in his excellent new book, Titanic’s Last Secrets. Like insects in their billions at the bottom of the world’s food chains, the tiny bolts brought the mighty ship low: a metaphor for class struggle if ever there was one.

Top 10 Greatest Female Film Characters

Top 10 Greatest Female Film Characters

Well I think Titanic was a romantic film but I never realized that it was a comedy, silly me. You have some wicked sense of humor which I liked very much. You added very humorous captions to the pictures you added to this post.

So glad you enjoyed this, PWC. Thanks for dropping in!

"She can't float."

Didn't realise it was a comedy!! I may have to watch A Night To Remember for the witty repartee!! 🙂