Movie Review – Pinocchio (1940)

Pure, cinematic gold. While many people will probably skip this film in favour of the latest CGI mush from Dreamworks, Pinocchio deserves to be seen large and proud here in a digital format, full colour and larger than life. After all, the popular character from Shrek cannot be the only way kids today know of the famous marionette. Surely. Pinocchio is an animated masterpiece, and should not be missed.

– Summary –

Director : Ben Sharpsteen, Hamilton Luske, Norman Ferguson, T. Hee, Wilfred Jackson, Jack Kinney, Bill Roberts.

Cast : Voices of Cliff Edwards, Dickie Jones, Christian Rub, Evelyn Venable, Walter Catlett, Charles Judels, Frankie Darrio, Thurl Ravenscroft.

Year Of Release : 1940

Length : 88 Minutes

Synopsis: When a wooden marionette is transformed into a living entity by the Blue Fairy after a lonely toymaker makes a wish, to prove himself worthy of becoming a real boy, he must prove himself brave, truthful and unselfish: which is harder than it seems with so much temptation around him.

Review : Pure, cinematic gold. While many people will probably skip this film in favour of the latest CGI mush from Dreamworks, Pinocchio deserves to be seen large and proud here in a digital format, full colour and larger than life. After all, the popular character from Shrek cannot be the only way kids today know of the famous marionette. Surely. Pinocchio is an animated masterpiece, and should not be missed.

**********************

This film is a magnificent cinematic achievement. And that’s putting it lightly. Disney’s Pinocchio is a devastatingly lavish, luscious and delightful animated feast for the senses, both artistically and musically. Barely a frame of this film is anything less than perfection. It’s golden, a warm, frightening, often poetically made film filled with lovely characters and a sense of the sublime. This, quite simply, is Walt Disney at his absolute finest. As each of these classic films are released on DVD and BluRay as part of the Platinum Series, I keep being blown away with just how… well, awesome each of these early films actually are. A lot of people give the Disney Corporation a bit of grief these days about their overt commercialization, and their somewhat cavalier attitude towards their inherited legacy of animation. And to some extent, perhaps that rightly so. After all, Disney have successfully whored their product out in a variety of ways that has effectively distilled their wares into nothing more than soft-core family-oriented slop: direct-to-video sequels of their most enduring and popular characters, for example, is only one instance that I can cite where they’ve tarnished their massive history.

So it’s a great shame that a lot of people may not ever take much notice of cinematic marvels like Pinocchio, Cinderella, Lady & The Tramp, to name a few, which have been given the deluxe treatment in recent years. And they are the poorer for it. Pinocchio, like the previously mentioned films before it, scrubs up an absolute treat on DVD today, and as I watched this marvelous film, for perhaps the first time in a decade and a half, maybe longer, I am reminded again of just how potent and significant a cinematic force Walt was back in his day. A string of commercially successful feature length animated films set his company up into one of the giants of the industry, at least creatively, something the current incarnation of Disney is sadly unable to claim. With Snow White, Walt bucked the critics and assaulted cinema-goers with a colorful, musical, narrative masterpiece; a sample of storytelling that has since echoed down through the years in almost every animated film created since. With the exception of, perhaps, Fritz The Cat. Thanks Ralph Bakshi.

Anyway, back to Pinocchio. Pinocchio was originally a serialized story by Italian writer Carlo Collodi at the end of the 19th Century, and published in a magazine known as Il Giornale dei Bambini, and while the author was at the time unaware of just how popular his creation would eventually become, the seed of the idea was cast upon Walt Disney as a follow-up feature to Snow White. Of course, with the exceptionally mammoth results achieved by Snow White, Walt had a particular problem to deal with: what on earth could possibly top the famed dwarfism-inspired fairy story? Simple: a moral fable about a wooden boy, seeking to become real, and the (mis)adventures he becomes involved in with his conscience by his side, embodied, this time, by a small cricket. Yep, sounds simple, right?

Wrong. The history of Pinocchio as a character, and his transformation into a screen legend, is a long and winding one. Disney encountered several problems with the story when he first conceived of it as the second feature film his studio would make. First, Pinocchio as originally written would not be an endearing character to a viewing audience, since as Collodi wrote him he was a largely unlikeable and belligerent character, a wanton mischievous imp who learned through folly to become an upright citizen. Since Disney figured that most audiences wouldn’t go to see a film about somebody they didn’t like, he changed Pinocchio’s character to that of a wide-eyed innocent, a newborn (in a way) to the world in which he is “born”. Pinocchio, a wooden marionette carved by the toymaker Geppetto in his small Italian shop, is given the spark of life after Geppetto wishes he could have a son of his own. The Blue Fairy (who many people only know as the object of affection for Haley Joel Osment in Spielberg’s AI: Artificial Intelligence) swoops down from the stars to grant the toymaker his wish. Only, being a little bit of a bitch, she doesn’t make Pinocchio a real boy straight away, which no doubt she could if she wanted. No, instead, the Blue Fairy brings to life the recently carved marionette, complete with wooden joints and a pointy, pointy nose, and tells Pinocchio that he will only become a real boy if he’s good. A little like Santa Claus. Only without the red suit and reindeer.

Of course, being a wooden boy brings it’s own disadvantages, not the least is that you are considered by many to be a freak, for use only in carnival sideshows and circuses. Pinocchio, innocently unaware of just how bad the world really is, is quickly suckered in by Honest John, an uppity Fox, and Gideon, a mute cat. They quickly seize upon the potential for fame and riches, by selling a walking, talking marionette with no strings to a local artiste by the name of Stromboli, a violent and angry man who imprisons Pinocchio in a cage, destined for carnivals across the country. The film differs here in it’s presentation of the Fox and the Cat. In the original story, the Fox and Cat pretend to be blind and lame, and trick Pinocchio into giving up his money for school. Here, they have more lugubrious personalities, and instead sell Pinocchio to Stromboli for quick cash. Indeed, the true history of Pinocchio is never told in the film: in Collodi’s original story, a lump of talking wood is given to Geppetto to carve, inevitably becoming the wooden boy, while in Disney’s take on it he’s simply a silent, still hunk of timber that is brought to life by the Fairy. Whether this adjustment by Disney can be counted as for better or worse is a matter for historians, although I think the Disney version truncates the story to a more manageable size. Instead of the mystical mysterious talking tree trunk taking shape as a boy, we see Pinocchio already carved.

We first enter the story with the magic sound of the song “When You Wish Upon A Star”, which became so popular the Disney company is virtually synonymous with the tune, in fact, they use it as their unofficial logo “theme”. Sung by Jiminy Cricket, we learn that Geppetto is seeking a son, and casts the first wish upon the wishing star in order for it to come true. Jiminy Cricket, it must be mentioned, gets short thrift in Collodi’s original story. According to the story, the cricket (who is not named) gives Pinocchio a piece of advice that causes the wooden boy to throw a hammer at him, killing the insect immediately. In shades of Obi Wan Kenobi, the cricket later return in ghostly form to advise (taunt?) Pinocchio during a later adventure. Disney decided to use the cricket as a conscience, a voice of rationality if you will, which would hook the human viewers and give the film a central character with which to empathize, as Pinocchio’s story is relayed to us. Jiminy is given the task of teaching Pinocchio the difference between right and wrong by the Blue Fairy, and thus becomes his (our) guide through the story.

So, Jiminy Cricket is born, and he is a delightful character indeed, a real Disney-fied creation filled with humor and a good nature. Flawed, yes, since he gives up on his charge at one point. Yet his resilient determination is what endears him to us, a character who can see beyond merely the superficiality of the situation to the larger picture: and his decisions serve to hinge the story and develop it through Jiminy’s own growth as a character. Jiminy accompanies Pinocchio along on his first day of school, only to have the young puppet side-swiped by Honest John and Gabriel, who tell him he be famous performing in Master Stromboli’s puppet show. Pinocchio is quickly sold into slavery by Honest John, who tells of his amazing good fortune to a man known dubiously as The Coachman, a man who takes badly behaved boys to a place known as Pleasure Island. The Coachman, a devious and cruel man, snatches young boys up with tales of fun and eternal frivolity on this mysterious island, and every night, takes a coach-load of ill-begotten lads to there. Pinocchio, who is again lured away from the path of right by Honest John and Gabriel, and delivered into the waiting hands of the Coachman. Along the way to Pleasure Island, Pinocchio befriends Lampwick, a recalcitrant and arrogant youth who tries to influence Pinocchio’s innocent ways. Lampwick smokes, drinks, plays pool (oohh, the Devil’s game, idle hand’s and all!) and generally runs amok. When the coach arrives at Pleasure Island, depositing it’s load of boys on the shores, they are at first overjoyed to be in a place catering for hedonism and bloated enjoyment. Rides, alcohol, tobacco, games and fun are all provided for the boys, and this unrestrained frivolity soon has dire consequences.

An unexplained plot twist has the boys on Paradise Island turning into Donkeys, or, in the vernacular of olden days, Jackasses, which was a kind of moral point for Collodi to frighten his readers into being good. You see, only bad children turn into Jackasses, while the good ones remain human. The analogy therefore, of the boys of Paradise Island being turned into donkey’s, again indicates the kind of debauched behavior that brings about consequences that will cause grief and pain to those who think they’re above the law. In a terrifying scene, Lampwick himself transforms into a donkey, the overwhelming pain and anguish of this writ large on the characters face, his voice disappearing into the harsh bray of the ugly, load bearing mammal. Pinocchio himself begins the transformation, growing large ears and a tail, before Jiminy Cricket arrives to whisk him away to safety… well, at least, the safety of the sea.

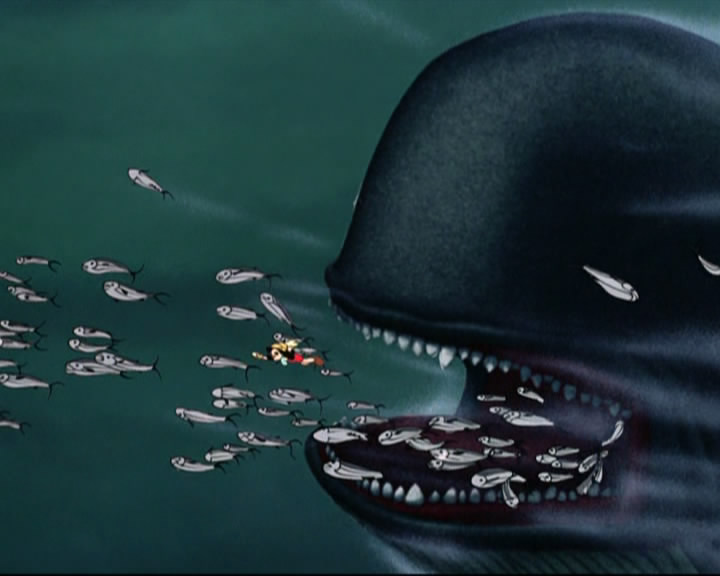

Arriving home to find Geppetto gone, Pinocchio seems disheartened, until a note from the Blue Fairy informs him that his father is stuck inside the belly of a massive whale, named Monstro. Strange, this biblical reference seems to often go unheeded by many, the Jonah-analogy is not lost on me. Pinocchio and Jiminy take off in search of Monstro, and in one of the films more intense sequences, they discover that Geppetto is indeed trapped inside the massive animal, marooned on an island in Monstro’s stomach. The reunion for Pinocchio and Geppetto is brief, as their situation is dire indeed. But Pinocchio has a plan. His intent is to escape by making Monstro sneeze, by lighting a fire inside the animal. The plan works, but not before they are almost sucked back into the gaping maw of Monstro’s mouth several times.

A highly animated chase ensues, with Geppetto and Pinocchio, along with Jiminy Cricket, managing to escape from Monstro’s grasp. But Pinocchio pays the ultimate sacrifice, having drowned in the effort of escape. Filled with sadness, Geppetto returns home with his son, to say farewell. But the Blue Fairy, now convinced that Pinocchio has proven his worth to become a real boy, changes the puppet into a human, allowing for another, happy, reunion between father and son.

Pinocchio as a film works on a multitude of levels. At first, it’s a genuinely enchanting fairy story, filled with mythical and magical elements that, for reasons unbeknownst to us all, seem to work when they perhaps shouldn’t. The story is a typically moral Disney one, filled with the kind of ethics and behaviors we would all like our own children to inherit. This is to be expected, since the studio prided itself on upholding the values and beliefs of a freedom loving public. Issues like responsibility, doing the right thing, trusting in yourself and not being swayed to the wrong thing by others. Disney’s Pinocchio, a changed version of himself from Collodi’s original story, is unaware of the differences between right and wrong, an innocent betrayed by the evil and callousness of his fellow man. Collodi’s original story had Pinocchio being aware of his indecent behavior, and relishing in it. Personally, I am glad Disney took the route he did.

The film looks stunning. In fact, this is perhaps the most amazing thing about Pinocchio, is the lavish, colorful and utterly captivating artwork on display here. The framing and style of this film are simply gorgeous to watch, almost every frame is a masterpiece of design and animation. The hues, the vivid coloring, the textural and captivating backgrounds; all working in effortless synchronization to really pull you into the story, a kind of visual feast for all your senses, if you will. Well, except touch. Still, certain scenes are utterly dazzling, even by today’s standards, to watch. The moment the Blue Fairy arrives for the first time, her translucent body a fabulously subtle effect (you can see right through her!). The desolation Geppetto feels as he searches in vain for his son, who is trapped in Stromboli’s wagon as they pass him by. The darker, more resounding themes, seem to resonate more within this film than anything else. The final battle with Monstro, the whale and the seawater coming in for some of the most astounding animated scenes ever committed to celluloid. And I don’t say that lightly. Pinocchio looks amazing, and if this is the dazzling job Disney have done in restoration of their classics, then they are to be applauded. The film is presented on DVD in it’s original 1.33:1 aspect, meaning on widescreen monitors you’ll have the old black bars down each side of the frame if you have your setup correct. The audio has been given a bit of a workover as well, afforded this time round with Disney’s patented Home Theatre Mix, which is of dubious necessity overall. A lot of cinema purists will lament the lack of an original audio track on the new DVD version, which would have been a fairly thin, innocuous mono soundtrack: here, the full 5.1 mix is presented, even though the soundtrack never once utilizes this to it’s advantage. Still, the audio available on the DVD is well presented in any case.

For lovers of extraordinary animation, and those of you seeking a wholesome, fully realized cinematic event, then this new release of Pinocchio is definitely for you. Children of all ages will fall in love with the little wooden boy, whose nose grows as he tells more and more lies. Morally, the film is quite well developed, since the central character learns life lessons as the story progresses, so it’s great for developing minds. For the adult, there’s enough joyous material within the film to more than keep you interested. The opening sequence, with the plethora of coo-coo clocks is particularly wonderful, a lengthy moment of levity in what is, essentially, a fairly dark and terrifying narrative. After all, people turning into donkeys (and we never see then changed back, so the mental image is quite startling) is not your run-of-the-mill story, is it? Nevertheless, this animated classic is really, truly, just that. A classic. And you should see it, if you haven’t already.