What Makes Me Think I Know About Films?

In my day to day life, mainly at work in the office, people often ask me for my opinion on various films that they’ve seen, and what I thought of them (if I’ve seen them too). To most film critics, bloggers and cinema lovers, especially the “serious” type, this will be a common occurrence. There will always be a person in your social group, be it at work, through friends or family, that is the go-to guy or girl for all your general information about films. When a film was made, who directed it, and how many Oscars it got; all relevant information a serious film fan, heck, even just a casual one, would and should know. Quiz nights become a must-attend event, because all your friends know that if somebody asks who directed the little known black & white doco about extinct forest-dwelling pygmies who ate their own poo, it’s gonna be you that provides the answer. You stupid schmuck.

It’s as if, by some fluke of cosmic alignment, you (and by that I mean myself and anybody else who writes film reviews or articles) have become the de facto Leonard Maltin of your friends. Because you watch a lot of films, and probably have a keen interest in film and all its sub-groups, people assume you’re knowledge and appreciation of the medium is of a heightened standard than the rest of the mere mortals who steal your oxygen. Which begs the question: what makes me think I know about films? Does my predisposition to enjoy a good action film, as well as the latest offering from David Fincher or a classic David Lean piece, make me in any way an authority on the subject? And why do I expect that my appreciation (or lack thereof) of various film genre’s gives me some sort of heightened ability to grant a film a score, of any kind? Consider the following a manifesto of sorts, a small indication of just where my thoughts on all this actually lie.

Film is, simply put, art. The art of putting sequentially shot still images in rapid succession through a machine beaming a light brightly onto a slightly curved screen in a darkened room. Or, in a modern sense, a series of frames of said still images onto a disc the size of a small saucer, played in high resolution via HDMI cable and viewed on one of a variety of flat screen monitors. Regardless of how it’s presented, the art of creating a story out of moving images is now regarded, perhaps wrongly, as a generic, anyone-can-do-it form of expression. Anyone with a handycam can make a “film” these days; just ask the people who made The Blair Witch Project, Paranormal Activity and all that other low-budget stuff… The YouTube generation have become accustomed to films being made, uploaded and disseminated across the Web by everything from the latest HD cinema camera to an iPhone, and assume that because it’s so easy, just about anyone can make a film. I disagree, because I think only people with talent can make something that has the right to be called a film.

And what of the impact of film to generate emotion? Sure, DaVinci painted ceilings, Michael Jordan shot hoops, Johnny Holmes made men envious with his prowess, but a film, and those who create them, can move entire cultures in a different direction. Film directors, much like DaVinci (I doubt Spielberg would appreciate a comparison to John Holmes!) with his brush, craft a story from the printed page and onto a screen by using a series of tricks, traps and artistic flourishes, bringing together both acting, sound and music, as well as a finely edited film stock, to produce a piece of entertainment that is as eternal as the Birth Of Venus. And as captivating.

And just like Rodin’s Thinker, Mozart’s Requiem Mass, or even the cave paintings of the Pitjantjara people, a film can be appreciated, abhorred or ignored by all and sundry. It’s a work of art, put together by a person for the edification or entertainment of another – usually a lot of others. Where Mozart once stated that if just one note (of his music) was changed, the entire piece of music would be altered, so to a film has everything in its place, and should that thing be changed, it would be a different film. Directors Cut indeed. Often, these works of art attain classic status, as is the case with, say, The Sound Of Music, Metropolis or Citizen Kane, while others attain that status for being puerile pieces of garbage, like Plan 9 From Outer Space or any film directed by Uwe Boll. Which says a lot for Mozart, in that for every Beethoven there’s a Tiny Tim or Spice Girls just around the corner.

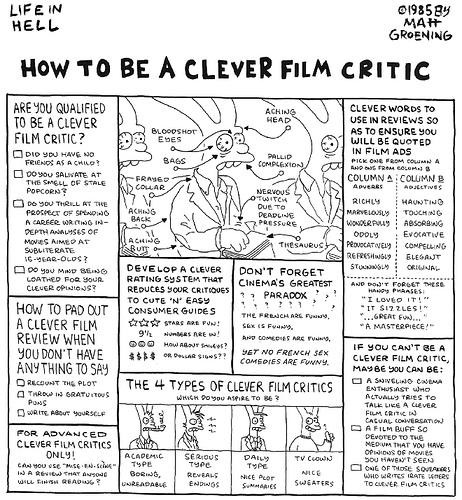

The fact that I had a different opinion than a work colleague about a recent film (Shutter Island) caused me to question what made my opinion on a film better or worse, or more regarded, than somebody else’s? Here I am, churning through review after review like I know what I’m on about, drunk on the power of site visits and comments, when for all I know I could simply be a cinema-boor, a man for whom only the most trashy, intellect-free cinema adventures are the most exciting. I get wound up over Armageddon, and when people trash it I have a little chuckle to myself, because I find that I can appreciate just how stupid a film it is, and yet I still find myself grinning like a serial killer while I’m watching it. I like to think I’m capable of enjoying a film simply for the sake of enjoying it, rather than trying to find a life lesson in every frame, or an underlying subtext in the closing credits. A difference of opinion on Shutter Island, while initially a fairly benign event in itself, unleashed in me a yearning for self-discovery of my own cinematic boundaries. Why did I like what I liked, and what made me dislike a film that others enjoyed? Everyone considers Beethoven’s 9th Symphony to be his greatest, right? Ask a serious music buff, one of those scarf-wearing pipe-smoking knitwear types who listen to the latest by Elgar like it’s Top Of The Pops, and you’ll find a wide variety of responses amounting to an argument between the 9th, the 5th (the one used in Fantasia) and the Eroica (the 3rd). Ask an average Joe in the street, the shopping-trolley pushing, two-screaming-kids dragging, dented-rear-fender man in the street, and you’ll probably get the 9th as being the best more often than not. Does knowledge and understanding of a thing make a person more able to quantify an argument either for or against that thing? Does my knowledge of film, such as it is, make me more or less approachable about answering somebody’s wailing “What did you think of Resident Evil?”. Most people would say to that: “Milla rocks”, or “The effects were cool”, but a serious film buff such as myself would have to weigh up the quality of production, the directorial nuances and choices, the quality of acting and appropriate levels of violence, sex and vulgarity, as well as how well all these things worked with the scripting and the editing, to make an informed decision.

Shit, am I capable of giving somebody a straight answer these days, about a film I’ve seen? Or will my work colleagues continue to raise one quizzical eyebrow and mutter “yeah, but is it any good?”. That’s the question I need to ask myself.

The great thing about film is that it can provoke such varied reactions in everyone, that it will always lead to a discussion about the ideas a film presents, or at the very least, just how stupid Lucas was in giving us Jar Jar Binks. The learned Film Student types, people I’ve previously described as the knuckle dragging high-nosed cine-pigs of this world, who think a film can be dissected in a classroom to determine its artistic merit, would argue a point until they required medical assistance from the knife I jam in their eye. Those are the kind of people I detest, those who view a film as something to be broken down and analysed to death. Like the poonces who try and find patterns and things in music and literature, you know, those wankers. I can’t stand those kinds of people. They’re there to make film less about art and more about science, a kind of “behind the magicians code” mentality that wants to know just how “they” did it. If only those self centred morons made films themselves, perhaps they’d understand just how hard it is. So when people thumb their noses at a certain film, decry it for being less than perfect, they can appreciate just how much work has gone into creating something that has the potential to change a persons life.

Films can change people. I hate to get all religious here, but if books like The Bible, The Koran or The Secret can change people spiritually, emotionally and personally, and if music can do the same (I mean, whose life didn’t change the first time they heard Beyonce squark “All the single ladies”?), then film can as well. Some of the great films of our time have affected social change, entered popular culture and brought about a shift. Admittedly, a lot of films haven’t achieved squat, but I think the medium of film offers us, perhaps moreso than music and literature, a chance to examine social and cultural taboos, relevancy and ideas that often become swept under the carpet. Which is all a little deep to be discussing here, but I want to make sure you understand that I believe that film offers so much more than simply a way of selling popcorn and 3D glasses. I have to believe that film can improve society, can embolden somebody to make a change, to bring about shift and impart wisdom. Or, you can simply watch a Michael Bay film.

Oh, Edward Elgar’s been dead since 1934. There’s nothing new about him. It was an ironic joke, fools.

While I try desperately to bring this piece back on topic, let me just ask this: what makes you think your opinion of a film, any film, is any more or less relevant than somebody else’s? Are we, as film reviewers, putting ourselves up as judge, jury, and executioner on somebody’s work of art? And what gives us that right? The right to free speech? What about the right of the film-maker not to be chastised for a directorial faux pa ’til the end of time? What about the right of an actor to deliver a substandard performance and for that, forever be castigated to the back pages of the tabloid rags? I often think about how I’d want my film, my work of art, to be perceived and received by audiences, and how I’d want their experiences to reflect the work and effort I’d put into it. Appreciating Michelangelo is easy. Appreciation Jackson Pollock, not so much. Why is that, though? Am I bound by populist opinion, an opinion formed not by actually looking at those works of art but by reading of other’s opinions of them, to simply repeat said opinions verbatim? How should I begin to compare the differences film brings us: the work of Alfred Hitchcock compared with, say, the work of recent David Fincher or Steven Spielberg? Different eras, different social commentaries, yet each equally brilliant in their own ways. How can any comparison be fair and equal?

I like to think I have the ability to appreciate all forms of film, from children’s animation to hard core porn. Okay, not so much the porn (after all, what’s to appreciate, really?), but I am able to differentiate between serious society examinations and gung-ho, action adventure fluff. And enjoy a film for its own sake. Unlike many critics, whose words cut like a knife into the conceptions of their readers about how great or terrible a film may have been, I try to be as balanced and even-handed as possible. I want to enjoy a film I see. I go into it with the expectation that I’ll like it, regardless of tone and style. I’m open-minded enough not to be an art-house snob, nor a Scary Movie-comedy lover, but an appreciator of trying to entertain people by making a film. If a film doesn’t entertain me, I’ll at least make an effort to explain why. And I’m able to accept that you, dear reader may not always agree with me. Which is fine, because we can’t all enjoy everything. When I write a review, I like to think I approach a film with as much integrity as possible, and not simply look forward to finding new and funny ways of insulting those who made it. I do bang on about George Lucas’ inability to craft a coherent and structured narrative, but I’m the first to admit that the man has one hell of an imagination. George hasn’t the understanding of his own film-making weaknesses, which has worked to the detriment of the Star Wars franchise in recent years. Knowing my own ability, my shortcomings in appreciating film, is perhaps the thing that defines me as a critic.

I don’t know everything, and God help you all if I thought I did.

If I'm not mistaken, Gertrude Stein once said: "All art aspires to the cinema".

And as we know, great art demands a great audience.

I tend to think great art will find it's audience regardless. But I do see your point, Mark!

Awesome post, and I think you got to the point quite well 😉 I guess you already know my opinion on the subject, but the first paragraph, not only did it make me laugh, but it was an exact refelction of my own life! I sure don't know that much about film, but out here in Alabama where sports and football is supposedly the meaning of life, they sure think I do!

I feel your pain, Matt. I really do!

Excellent article Rodney and it throws up a whole host of questions.

I have battled with the thoughts that if I was a filmmaker and was having my hard work harshly ripped to pieces by a critic who had never picked up a camera in their lives, I'd be mildly annoyed (to put it lightly). I like to think that as I have a background in television production and have put together a few short films myself my reviews comes from a place of some experience. But even then, I try to write my opinion as fairly as possible of the film in question. That is – honest criticism/praise that is based on my own personal attraction or lack of attraction to the film in question.

That's all you can ask from a review. How did the film affect the reviewer on a personal level and how does that merit or demerit the film.

I do agree that film can be a powerful cultural and societal commodity for better and for worse. Certianly, the films that I have grown to love over the last few years are ones that shed light on particular moments in life we all go through. Films can be a source of guiding inspiration.

Just to clarify a little… i *adore* 300 but, as a writer, i gotta say the dialog is a white russsian in a condom: hard to swallow. Which is why i say it's a guilty pleasure. That said, and exactly like The Pretty Reckless, i'm totally able to defend it honestly and sincerely on other merits (in the case of 300, the cinnamon-tography (or whatever you professionals call it) is estopifying–i.e. so good they haven't invented a word for it yet).

Like good beer or…beer, i guess, it all comes down to a question of taste. i respect your opinion because, as a film maker yourself, you know a lot about the medium and the sheer volume of movies you've seen make you more qualified than a 10-year-old who's only seen a handful of Disney things. You can judge one film against another and compare one aspect of a film to the same aspect in a hundred other ones and say which you preferred most and why. Beyond that, it's a question of what you like and what you don't like. i know i'm not supposed to like "300", The Pretty Reckless or licking the tops of c batteries but i do and that's just the way i roll. There are two aspects to any review, i guess is what i'm saying. There's the analysis part and there's thee opinion part. The analysis makes it interesting and the opinion makes it fun, but both are necessary to a good review.

@ Castor – thanks man! i think you're right about trying to be even handed in judgement, especially for a film that's virtually unwatcheable for whatever reason – a good film critic should be able to explain why it's a bad film, rather than string together en endless stream of insults and degradation that, while maybe justified, doesn't help a reader develop an accurate opinion of said piece.

@ Al- man, you always know just how to say the stuff I can't. i think we need to write a book on something: me to write the prose, and you to come along and make it funny. And anybody who doesn't like 300 needs stabbing. That's a damn awesome film and anybody saying otherwise hasn't watched it.

Cheers for the feedback fellas!

Great post Rodney. Like you, I do my best to be even-handed in my judgment and I always keep in mind that in every film — good or bad, there were people who worked really hard and poured their soul into it. The worst critics are the ones who criticize and call names but never explain why. I totally agree that movies can change people. After all, the sole common theme of every single film worth its salt is identity and we watch movies to learn more about ourselves. What can this film tell me about myself?