Movie Review – Vertigo

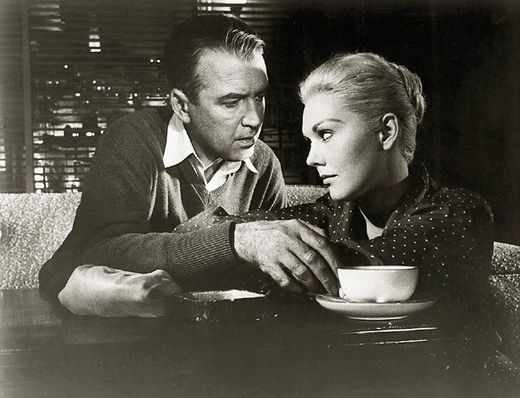

Principal Cast: James Stewart, Kim Novak, Tom Helmore, Barbara Bel Geddes, Henry Jones, Raymond Bailey, Ellen Corby, Konstantin Shayne, Lee Patrick.

Plot Synopsis: A former San Francisco police detective juggles wrestling with his personal demons and becoming obsessed with the hauntingly beautiful woman he has been hired to trail, who may be deeply disturbed.

**********

A while back, we were approached by fellow film blogger Camiele White about writing an article for fernbyfilms.com, an offer to which we quickly agreed. Camiele has been hanging around the blogosphere for a while now (more info on her at the bottom of this post), and we were quite chuffed at her kind offer to scribe a few words for our site. Our thanks to Camiele for her time, and without any further faffing about, we present her work here for you now! Read on!

Alfred Hitchcock has long been considered one of the most visionary directors to ever invest his heart into film. It goes without saying that his understanding of perspective, lighting, and shadow remain miles beyond his contemporaries and even more glaringly those who followed in his footsteps. But, there is one aspect of the man’s genius that many have neglected to praise as much as his ability to twist cinematography to fit a story: his understanding of metaphor.

From his work in the film Vertigo, it was especially interesting to me to note Hitchcock’s dedication to the extended metaphor of circular motion. In poetry, we call that a conceit. I always thought of it as a tool used in the same way a narcissist uses a mirror: to always stay focused on itself. In the same way, Hitchcock used the conceit of vertigo (motion sickness that takes the peculiar form of a sudden wave of dizziness) to further explore the idea of chasing something continuously without ever actually fully grasping its significance. The man, surely, was a poet.

The story follows Detective John Ferguson, played by the masterful James Stewart, who has developed a debilitating fear of heights that has seen him take leave of his daily detective duties. When commissioned by an old college mate of his named Elster to follow his wife, Madeleine, things become as dizzy as the film’s namesake. Ferguson, also known to his acquaintances as “Scottie”, is pulled into a dark puzzle as sinister as the sickness that holds him captive. Madeleine has mysteriously fallen victim to an alleged spirit possession –the spirit of her great grandmother, Carlotta Valdes, has infiltrated her body and continues to take her places she doesn’t remember being. He follows her to an art museum where she’s seemingly transfixed by a portrait of her great grandmother, whose bun is, incidentally, tied in the same spiral as hers. He follows her in circles, always turning corners, always finding dark crevices in which this mysterious woman hides –Hitchcock’s sense of poetry at play.

This possession culminates in Madeleine “falling” into the San Francisco Bay. From this moment on, Scottie finds himself rather enamoured with a woman whose spirit is twisted in knots. She has a cold demeanour, demure and very much aware of her power over the weaker sex.

Being in the incessant company of Madeleine drives Scottie to devotions he never thought he’d ever entertain, much to the chagrin and devastation of his close friend, (read: lover) Midge. A continuous cycle of madness follows the female characters in the film, causing a rupture between sanity and obsession. Scottie badgers Madeleine for answers, retracing step after step after step, forcing her to go deeper into the darkness that clouds her head like the eye of a hurricane.

The obsession continues into something dangerously unreal. Madeleine runs into an old church’s bell tower; knowing about Scottie’s agoraphobia, Elster knows that he won’t follow. What he witnesses as Madeleine falling to her death is an elaborate plot to cover up the death of Elster’s real wife. Scotties mind cracks at the sight of Madeleine committing herself to a fabricated inevitability.

After being released from a hospital to cope with the trauma he’s faced, Scottie runs into a woman that he swears looks exactly like his late lover. Circular motion –everything leads back to the beginning. He forces his new lover, Judy, to change everything about her: her clothes, her hair, the way she does her make-up. She complies through much pressure from Scottie and a conscience full of guilt.

The obsession and paranoia continue to unravel. Scottie takes his new Madeleine to the same church where he perceived her to fall to her death. Each line is revisited, each sentiment, step by step by step, up and up, into the belfry, his eyes continuously looking down the winding steps as the vertigo clenches sways his step. He finds out about Madeleine’s deception, about Elster’s real wife and the plot the two of them had to get rid of her –circular motion, going back to the beginning, back to the source of the obsession.

Then suddenly, they enter the bell tower: shadow, grit, darkness. Then a figure rises from the corner. Judy is sure that it’s Elster’s real wife, coming back to reclaim the life that was rightfully hers. She screams. She jumps without hesitation out the belfry window –only to be given her last rites as the figure shows itself to be a nun. Scottie is left on the ledge, staring down into the darkness that had finally pulled Madeleine in.

The film never stops spinning. Every time we find ourselves unravelling a new piece of the puzzle, another is revealed, leading back to the beginning. It’s Hitchcock’s poetic sense of reality and film-making that has etched this film as his most celebrated and certainly kept his image at the forefront of noir, suspense, and storytelling. With every part of my being I realise that there is no film industry without Alfred Hitchcock –his fears played on those of everyone who went to see his films, no fear more palpable than that of deception, being forced into a dizzying maze from which we can’t climb out.

***

As unexpected as her path was to loving all things weird, more unexpected is her ability to get attention for writing about the stuff. From Japanese horror and Korean melodrama, to the acid soaked animation of the 70s, Camiele White loves to talk about, debate, and watch film that teases, pleases, and f*cks with the senses. If you want to give her a buzz, she can be reached at cmlewhite at gmail [dot] com.

Rebecca is my favorite but Vertigo is one of Hitchcock's best.