Movie Review – Foolish Wives

A film made in 1922, about to broach its centenary, cannot withstand the critical eye of modernity, and it shouldn’t have to. Made in the period between the two World Wars, and featuring the 20’s equivalent of Stanley Kubrick in von Stroheim – who wrote, directed and starred in this thing – Foolish Wives attempts to be a clever sex melodrama; in modern context, it’s as sexy as sushi and as melodramatic as three rutting goats, but there’s an old-world charm and high-art sense of style that cannot be missed. I’m not a student of this cinematic vintage, and were I one I guess I’d find a lot more to like, but to my post-Y2K-millenial eyes there’s a whole lot of nothing going on here.

– Summary –

Director : Erich von Stroheim

Year Of Release : 1922

Principal Cast : Rudolph Christians, Miss DuPont, Maude George, Mae Busch, Erich von Stroheim, Cesare Gravina, Malvina Polo.

Approx Running Time : 140 Minutes (BluRay Release)

Synopsis: A conniving conman pretends to be a Count to fleece silly women from their money.

What we think : A film made in 1922, about to broach its centenary, cannot withstand the critical eye of modernity, and it shouldn’t have to. Made in the period between the two World Wars, and featuring the 20’s equivalent of Stanley Kubrick in von Stroheim – who wrote, directed and starred in this thing – Foolish Wives attempts to be a clever sex melodrama; in modern context, it’s as sexy as sushi and as melodramatic as three rutting goats, but there’s an old-world charm and high-art sense of style that cannot be missed. I’m not a student of this cinematic vintage, and were I one I guess I’d find a lot more to like, but to my post-Y2K-millenial eyes there’s a whole lot of nothing going on here.

**********************

Ego runs rampant.

The opening text (on the disc-release format) of Foolish Wives recounts the problematic history the film has had throughout the nearly 100 years it’s been around. To steal from the text itself, Foolish Wives (Erich von Stroheim’s third directorial effort) ran at a massive twenty-one reels upon its completion – von Stroheim intended the film to be cut in half and shown over consecutive evenings, according to the info I dug up online. The studio, Universal Pictures, refused this idea, and cut out over five reels of footage prior to release. A later version, cut in half yet again – to seven reels total – meant the film ran at about 117 minutes, a brief interlude for a movie intended to be some kind of monumental epic. The version I watched, a restoration version clocking in at an almighty 2 hours and 20 minutes (remember, this was a silent film, made in 1922, so length came at considerable cost), remains now the most complete version of the original cut von Stroheim completed, although it must be said that even at 2 hours and change, there’s little redeeming value in a film this long, featuring this little story.

Foolish Wives came out during Hollywood’s silent era, budgeted at a little over $250,000, and ended up costing somewhere between $1.2 and 1.4 million, depending on who you ask. To say it was a massive gamble is an understatement, and as noted by Variety at the time: “….was 11 months and six days in filming; six months in assembling and editing; consumed 320,000 feet of negative, and employed as many as 15,000 extras for atmosphere. Foolish Wives shows the cost – in the sets, beautiful backgrounds and massive interiors that carry a complete suggestion of the atmosphere of Monte Carlo, the locale of the story. And the sets, together with a thoroughly capable cast, are about all the picture has for all the heavy dough expended.”

For 1920’s Hollywood, this was extravagance writ large; considerable financial gain was probably not possible, leaving the film to stand on its merits nearly a century later with the benefit of modern cinematic literacy to compare against. The story – like many of the time – is largely played for melodrama, although nowadays it’s more quaint than actually provocative or salacious. Erich von Stroheim, pulling triple duty as writer, director and star, plays a conman calling himself Count Karamzin, who seduces the women of Monte Carlo and extorts money from them. One of his targets is the wife of an American envoy to France, played by Miss DuPont (often credited as Patty DuPont). The film’s budget and large-scale set, filmed in the studio backlot at Universal [see picture above], was mammoth for its time, with a young Irving Thalberg in charge of production. Thalberg would go on to become one of the most famous and powerful studio heads in Hollywood’s golden age, yet even he – in his early 20’s – couldn’t rein in von Stroheim’s massive ego-trip and spending. Foolish Wives is nothing if not lavish, with expensive sets and scenes featuring hundreds of extras playing a starring role. Variety got it right in stating that the film’s budget is entirely up on the screen.

What isn’t quite so easy to swallow these days is Foolish Wives’ inadequate storytelling methods. The silent era has never been a favorite of mine, and although I can appreciate the technological limitations and the talent of the stars to make their characters come to life for viewers who cannot hear them speak, the lack of dialogue really does hamper the story’s momentum and energy. For a film over two hours, to take so damn long in achieving anything, introducing characters of no or little value, and having the plot simply plod along instead of able or jog, Foolish Wives is excessively frustrating. The whole “seduction” plot the Count undertakes is lengthy and overly drawn out, and much of the humor of the era is lost thanks to too simplistic a style. This isn’t a criticism as much as an observation of the limitations film-makers had at the time.

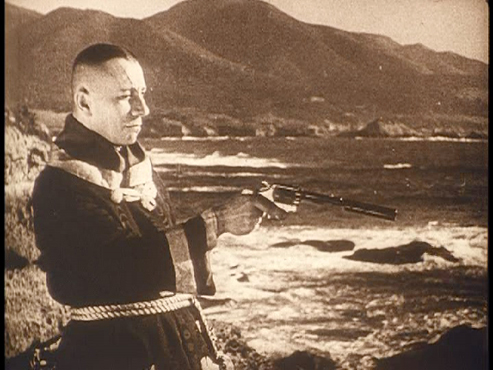

While the story of infidelity and women being fleeced by one of Hollywood’s least attractive leading men remains dubiously entertaining, the same cannot be said for the style von Stroheim puts on the screen. Even in its dilapidated visual state, Foolish Wives looks terrific in terms of framing, lighting and conceptual artistic merit. Von Stroheim knows how to light a scene, using harsh shadows to create a foreboding sense of malevolence to the Count, and soft focus for the womenfolk (most of the time), which I guess was the way you did it back in 1920, right? One of the more laughable sidebars I should point out is that it’s perhaps worth noting that von Stroheim has a ghastly Nazi-esque look about him the whole film, cropped hair and stern, admonishing disposition casting him in a negative light now more than it probably did at the time – the Count looks like a damn SS soldier, and von Stroheim’s strong Germanic features now make him inadvertently familiar as what one might term a “generic Nazi”. Perhaps hindsight isn’t such a great thing after all, eh? And I don’t think I’ve seen such a cool opening introduction to a character as the one von Stroheim gives himself in this one – standing over a beach firing a silenced six-shooter at a target; man, if that doesn’t speak volumes for the type of character he was, nothing does! Dude knows how to make an entrance!

Anyways…. von Stroheim shoots this film with vigor and style, and his visual cues are indeed reminiscent of the later work of Kubrick, some forty or so years later. There’s plenty of locked camera framing, often at weird angles and using the square aspect ratio to counterpoint the use of set design, doorways, corridors and other evocative visual cues to create an atmosphere of both decadence (this is Monte Carlo, after all) and giving his actors some really well constructed screen magic to work within. His use of focus is limited to the camera technology of the time, and no doubt he made the best use of placement as he could when filming on carriages, inside rooms and on live locations, so it’s a testament to his talent that the film is as visually potent as it is. Considering this film is well outside my usual cinematic purview, I spent a great deal of time marveling at just how widescreen it all was – even though it’s a rough-as-guts presentation featuring a chuckle-worthy Looney-Toons’ inspired piano score accompaniment (seriously, the whole 2 hour film is accompanied by somebody tinkling away on a piano with no noticeable theme or definitive sound-to-screen cues that make a lick of sense!) and featuring the stock-in-trade use of lens manipulation, aperture adjustment and considerably wordy interstitials. From a vintage standpoint, this is a highly technical film achievement and worth watching if for nothing but von Stronheim’s use of camera, lighting and style.

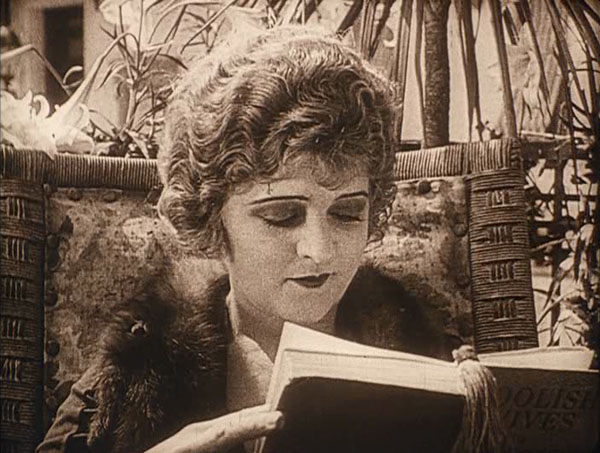

Von Stroheim aside, the cast are all… well, lovely isn’t the right word, but commendable comes pretty close. Nobody here acquits themselves as well as von Stroheim’s rampant ego – he’s in every single scene, almost without exception, the crafty bugger – instead providing support to the director’s whim of leading this thing from the front foot. Maude George and Mae Busch play female associates of von Stroheim’s Count Karamzin (they are all cousins, according to one title card), adding early sexy beauty to the story, but the fact that the set-up of the Count’s plan lasts for nearly thirty minutes on its own before anything else happens is just ludicrously extravagant. Miss DuPont is the focus of the female on-screen beauty here, though, as Helen Hughes, and although she’s… ahem, not my type, I guess for the era she’s the Angelina Jolie of the silver screen. Who would know – not I, I say.

Problematically for an ADD film junkie like myself, a lot of the characters in the film are introduced and disappear almost as rapidly in quick succession; one feels that it’s a parade of von Stroheim’s family all being “gifted” a role in the film, and although it’s nice to see other faces on the screen, they bring nothing to the story other than length. Von Stroheim’s idea of his own self worth is evident in the fact that he’s hardly ever out of frame, to the point where close-ups on his co-stars are shorter by a considerable degree than when the camera is aimed at him. The lack of coherence in understanding who most of the people in the film actually are – and call that a byproduct of my generational inability to think outside the box – leaves me lamenting for a vocal soundtrack even more.

If you’re a fan of silent film, and have perhaps studied the career of Erich von Stroheim, you’ll find a lot to like in this film – indeed, from a technical standpoint it’s a marvelous work of art – but for casual viewers and first-time silent-era audiences this one is something of a chore to get through. The melodrama doesn’t work now, the characters and arch acting by several cast members (not to mention some of the hideous 1920’s film make-up styles) simply highlight the period and limitations with which the film was made, rather than involve you in the story. Foolish Wives is structurally ambitious, un-reacheably driven by von Stroheim’s fatuous ego, and contains plenty of really nice cinematic elements of lighting and production that feel modern even by today’s standards. Keeping the vintage in mind, Foolish Wives is a cursory entertainment of perplexing indifference, almost time-capsule ridicule, lacking resolute structure and replacing it with plodding, hubris laden extravagance that filters through into the Ocean’s 11-esque story of taking rich people’s money..