Movie Review – Great Dictator, The

Principal Cast : Charlie Chaplin, Paulette Goddard, Maurice Moscovich, Emma Dunn, Bernard Gorcey, Paul Weigel, Chester Conklin, Jack Oakie, Reginald Gardiner, Henry Daniell, Billy Gilbert, Grace Hayle, Carter De Haven.

Synopsis: Dictator Adenoid Hynkel tries to expand his empire while a poor Jewish barber tries to avoid persecution from Hynkel’s regime.

******

The biggest middle finger to Hitler, ever.

If there’s a modern cinematic approximation of Charlie Chaplin’s spot-on satire of Nazi Germany, it would be Kubrick’s Doctor Strangelove. The Great Dictator is an absolute goldmine of satirical jabbery, a knife to the white underbelly of Hitler’s cruel and evil despotic rise and a rancorous ode to conformity and mindless fascism. Creatively, it’s a work of genius, a pointed advocate for democracy and freedom of speech and belief, and at its heart a poetic remonstration for love of humanity – something Hitler patently did not do. Filmed just following the outbreak of World War II, and driven by Chaplin’s disdain for what her saw in Hitler’s rise to prominence and the regime’s treatment of the Jews, The Great Dictator skewers the infamous leader as a nonsensical dilettante, a costumed dandy with limited intelligence surrounded by preposterously named yes-men.

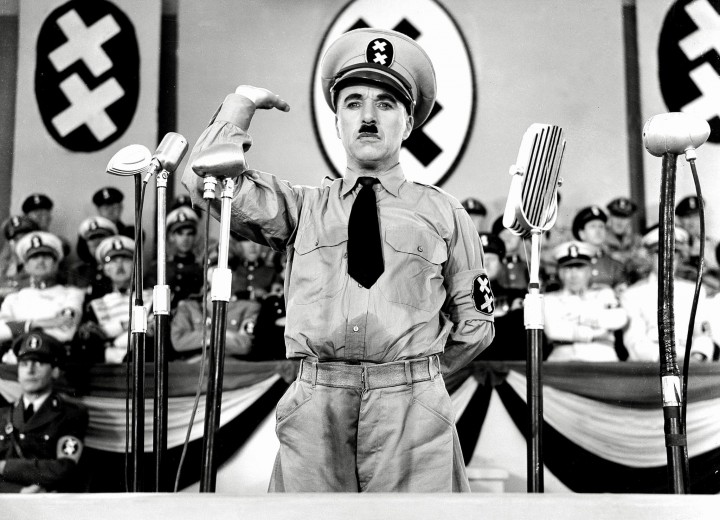

Seen as a product of its time, there’s little doubt The Great Dictator makes fun of significant portions of Hitler’s Nazi regime and its connotative evil towards minorities. Like many a wonderful satirist, Chaplin ably lampoons not only Hitler, using the man’s tectonic vocal delivery style during speeches (in nothing but German-inflected gibberish), but also Nazi iconography (the swastika is replaced by two X’s), and the inimitable jodhpur-sporting SS (referred to as stormtroopers continuously, which made me wonder when Darth Vader might enter the frame!) are given a buffoonish menace that’s not entirely without merit.

Seen as a product of its time, there’s little doubt The Great Dictator makes fun of significant portions of Hitler’s Nazi regime and its connotative evil towards minorities. Like many a wonderful satirist, Chaplin ably lampoons not only Hitler, using the man’s tectonic vocal delivery style during speeches (in nothing but German-inflected gibberish), but also Nazi iconography (the swastika is replaced by two X’s), and the inimitable jodhpur-sporting SS (referred to as stormtroopers continuously, which made me wonder when Darth Vader might enter the frame!) are given a buffoonish menace that’s not entirely without merit.

Chaplin plays the dual roles of both Hitler analogue Adenoid Hynkel, and the Jewish barber, who appears derived from Chaplin’s own Tramp character, with a sense of slyly discerned pointedness to the absurdity of the situation. While Hynkel is largely a “straight” character, in the sense that he’s surrounded by idiots and chumps but isn’t really one himself, the Barber is typically semi-farcical Tramp, even though Chaplin himself said it wasn’t the same character. The fact that both Hynkel and the Barber sport the Tramp’s iconic moustache (which, as was pointed out in the years following Hitler’s own rise) looks exceedingly like Hitler’s style is eerie – it’s a considerable fact that were a comedian to try and reproduce a similar look today, they’d immediately conjure up negative connotations, yet with Chaplin making the look world famous well before the German Reichsführer ever ascended, he gets away with it. Audiences coming to this film flat might be confused – is it the Tramp or not? – but one gets the sense that Chaplin’s Barber is a less flittery than the Tramp ever was.

The Great Dictator works best when it focuses on Hynkel and his cronies. It’s a hilariously on-point dialogue-and-appellation comedy in this regard – Hynkel’s offsiders are Herring (a riff on Herrman Goering, and played by Billy Gilbert, looking somewhat like Schultz from Hogan’s Heroes) and Garbitsch (well, that would be Joseph Goebbels, and personified by Henry Daniell), and via their bigoted conversations, most of which use direct inference to Nazi populist themes and make them sound like the utter wankers they were, The Great Dictator sings a song that makes fools of them with ease. Talk of killing the Jews (which happened, although Chaplin and most of America was unaware of it at the time) followed by “brunettes” (because true Aryan people are blonde) leads to a scene in which Hynkel dreams of being “dictator of the world”, and performs an iconic dance with an inflatable globe of the Earth. Seeing a Hitler-approximate performing a balletic dance while holding the world in his hands was, and still is, terrifying – we came so close to that happening – and it’s the power of Chaplin’s use of such stark contrasting imagery that makes this moment sing.

The Great Dictator works best when it focuses on Hynkel and his cronies. It’s a hilariously on-point dialogue-and-appellation comedy in this regard – Hynkel’s offsiders are Herring (a riff on Herrman Goering, and played by Billy Gilbert, looking somewhat like Schultz from Hogan’s Heroes) and Garbitsch (well, that would be Joseph Goebbels, and personified by Henry Daniell), and via their bigoted conversations, most of which use direct inference to Nazi populist themes and make them sound like the utter wankers they were, The Great Dictator sings a song that makes fools of them with ease. Talk of killing the Jews (which happened, although Chaplin and most of America was unaware of it at the time) followed by “brunettes” (because true Aryan people are blonde) leads to a scene in which Hynkel dreams of being “dictator of the world”, and performs an iconic dance with an inflatable globe of the Earth. Seeing a Hitler-approximate performing a balletic dance while holding the world in his hands was, and still is, terrifying – we came so close to that happening – and it’s the power of Chaplin’s use of such stark contrasting imagery that makes this moment sing.

The absurdity of Hynkel’s plans of world domination are explicitly denounced by one of his own men – Schultz (Reginald Gardiner) – who flat-out tells the leader his plans will fail because it’s built “on the stupid ruthless execution of innocent people.” Resound much? Chaplin might as well have had access to a time machine, he makes such a good point before its time. I guess human evil kinda goes around a lot throughout history. Hynkel’s animalistic performances, in which he growls and gibbers like some tiger, forces the film to confront the utter despotism a man like Hitler can command through sheer personality. The actions in the Jewish Ghetto of Tomania, echoing what happened within real-world Poland and elsewhere, resonate moreso now that we’re aware of the Nazi cruelty and tyranny after the fact – this edginess is seconded into a taciturn humour, but the modern eye of today looks back and grits one’s teeth at its prescience.

Perhaps the most famous of Chaplin’s moments in the film comes with its concluding monologue, a testament to freedom and humanity – a testament against evil of the kind prosecuted by the Nazis and by Hynkel’s absurdist power structure – and it sees Chaplin deliver a spear straight from the heart. In part, the speech is thus:

“You, the people have the power – the power to create machines. The power to create happiness! You, the people, have the power to make this life free and beautiful, to make this life a wonderful adventure. Then – in the name of democracy – let us use that power – let us all unite. Let us fight for a new world – a decent world that will give men a chance to work – that will give youth a future and old age a security. By the promise of these things, brutes have risen to power. But they lie! They do not fulfil that promise. They never will!”

The above lines could be inserted into any modern-day speech by a world leader and it would ring true as much now as it did in 1940. It’s a universal theme, the freedom of the people against tyranny, and Chaplin absolutely nails the point, ramming it home with an impassioned plea to all humanity not to allow evil to prosper.

Aside from its obvious wartime satirical barbs, The Great Dictator still contains plenty of uproarious moments of Chaplin-esque slapstick, a kind of palate-cleanser between the heavy moments of drama. Chaplin’s brilliant fight with a pair of Hynkel’s stormtroopers early in the film, as well as a brilliant moment in which he attempts to hide inside a wooden chest to escape capture (it’s a moment of acrobatic alacrity that I absolutely exploded with laughter at), to the Barber’s continual fidgeting with his hands and vaudevillian pratfalling, The Great Dictator features truly vintage Chaplin at his charismatic best. Hynkel’s blithering exposure to ridicule on his requiring a loan in order to launch an invasion on the neighbouring country of Osterlich (an approximation of Austria, the country annexed by Nazi Germany in 1938), as well as his belligerent treatment of his own subordinates, is captured in excruciatingly demeaning clarity.

The supporting cast are entirely excellent – Maurice Moscovich’s performance as an elderly Jew rings with a hint of genuine sorrow that what they’re acting isn’t really far from the truth, while Gilbert and Daniell are utterly hilarious in their respective roles. Watch also for the utterly hilarious performance of Jack Oakie as a Mussolini caricature, Benzino Napaloni, who arrives late in the film. Oakie snagged a Best Supporting Actor nomination at the Academy Awards for his work.

Also worth mentioning (aside from, you know, everything) is Chaplin’s writing and direction. The script positively sparkles (I’ve alluded to this) with irony, particularly a scene with Hynkel and Napaloni engaging in a verbal tete-a-tete, which reminded me greatly of Strangelove’s magnificent “you can’t fight in here, this is the War Room” moment: Chaplin’s direction is also superlative, his sense of comic timing absolutely impeccable. The cinematography, credited to Karl Struss and Meredith Wilson, is a wonderful monochrome experience, the use of lighting, framing and soft-lit exterior sequences bring the film’s obviously high-budget ($2 million in 1930’s money) production values, and while Chaplin’s camera doesn’t really move from a shoulder-high position throughout much of the film, the look of the film (it’s immaculate in HD, if you have the opportunity) is just dynamite.

In the exceedingly small sub-genre of War Satire films, most people will probably point to Kubrick’s Doctor Strangelove as the major proponent by way of example. I would suggest that Chaplin’s The Great Dictator is an even better one. It’s utterly brilliant: I would also suggest that the lessons we were given in a film near some 70 years old have yet to be learned by the human race. This is the Gold Standard of satire films – hell, of film in any form – and as such comes with my highest recommendation.

Amazing film with so many sequences, the speech, globe and the barber scenes being my favorite.

I was astounded by the "globe" sequence – it's so prescient, so telling and, in retrospect, so horrifying when you associate it with what the Nazi's accomplished.