Landmark Films Of The 20th Century – 1950-1959

In this, the sixth of our ten-part series on landmark films of the 20th Century, we identify films that set new benchmarks and new ways for film-makers to tell their stories – from editing, to sound, to visual effects, the 100 films we’ve unearthed are considered either classics (or should be) that changed the landscape of film forever. The films listed herein represent annual landmark achievements in cinema – they may not be the “best” films of that year, but they represent a leap forward in cinematic technique that is worth considerable attention.

If the 40’s were marked by the shadow of a global war, the 1950’s represented a rebirth, as the world began to feel the influence of cultural and artistic change. Whereas the war years were driven by both the Great Depression of the 30’s and the financial pit of military requirement, the 50’s saw a greater level of affluence across America and Europe than ever before. With it came social class warfare and rigorously divisive sexual, religious and political spectrums. A new form of music – rock’n’roll, arrived on the scene led by artists such as kids named Presley, Bopper, Orbison, and Cash. Radio was gradually giving way to cinema, but both were threatened by the rise of the newfangled technology that could beam pictures directly into people’s homes: television. To counter this audience-stealing threat, Hollywood gave us a new sampling of its nascent “epic” genre, utilising widescreen aspect ratios, gimmicks like 3D and “Smell-o-vision”, and better sound reproduction to pull in crowds. Instead of being a “night out” at the pictures event, cinema became more of a consumerist outlet for audiences, a casual, less up-market promise of fun and adventure beyond the doors.

Part VI: 1950-1959

1950. Treasure Island

Hard as it is to imagine, but at one point Walt Disney’s little animation studio had never made a full-length live action feature. For twenty or so years their output had comprised entirely of animated features, from Snow White to 1950’s Cinderella (the 12th canon film to-date). Treasure Island marked their first foray into the live-action market, a now-classic film based on the Robert L Stevenson novel of the same name, and out of the success of this would be born an entirely new sub-genre for the powerhouse studio. These days, Disney have parlayed their financial success into remaking their beloved animated films – Maleficent, which slants the Cinderella tale from the view of that story’s villain, and umpteen takes on The Jungle Book, remain eminently popular – and even spawned an entirely new division, Touchstone Pictures, to allow the studio to produce more adult-themed projects not normally associated with the family-friendly House Of Mouse. Treasure Island starred Disney alum Bobby Driscoll, who had appeared in now-censored Song Of The South, and Robert Newton as Long John Silver, with the film being the first to see the story in colour. For giving us a live-action Disney, Treasure Island is a true landmark of cinema.

Hard as it is to imagine, but at one point Walt Disney’s little animation studio had never made a full-length live action feature. For twenty or so years their output had comprised entirely of animated features, from Snow White to 1950’s Cinderella (the 12th canon film to-date). Treasure Island marked their first foray into the live-action market, a now-classic film based on the Robert L Stevenson novel of the same name, and out of the success of this would be born an entirely new sub-genre for the powerhouse studio. These days, Disney have parlayed their financial success into remaking their beloved animated films – Maleficent, which slants the Cinderella tale from the view of that story’s villain, and umpteen takes on The Jungle Book, remain eminently popular – and even spawned an entirely new division, Touchstone Pictures, to allow the studio to produce more adult-themed projects not normally associated with the family-friendly House Of Mouse. Treasure Island starred Disney alum Bobby Driscoll, who had appeared in now-censored Song Of The South, and Robert Newton as Long John Silver, with the film being the first to see the story in colour. For giving us a live-action Disney, Treasure Island is a true landmark of cinema.

Also in 1950: In Hollywood awards season, Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard and Joseph L Mankiewicz’s All About Eve would vie for the lions share of gongs, with the latter winning Best Picture at the Oscars, and the former taking the Golden Globe in the same category. Marlon Brando would make his film debut in The Men, while Jazz Singer star Al Jolson passed away following a heart attack, aged 64. Jimmy Stewart famously signed a three-film deal for a percentage of the film’s eventual gross, rather than a traditional flat studio fee, netting him a considerable sum when his first film, Winchester ’73 became successful. Stewart would continue to take back-end deals for his films and this method became a default for Hollywood performers now unshackled by the stifling studio system.

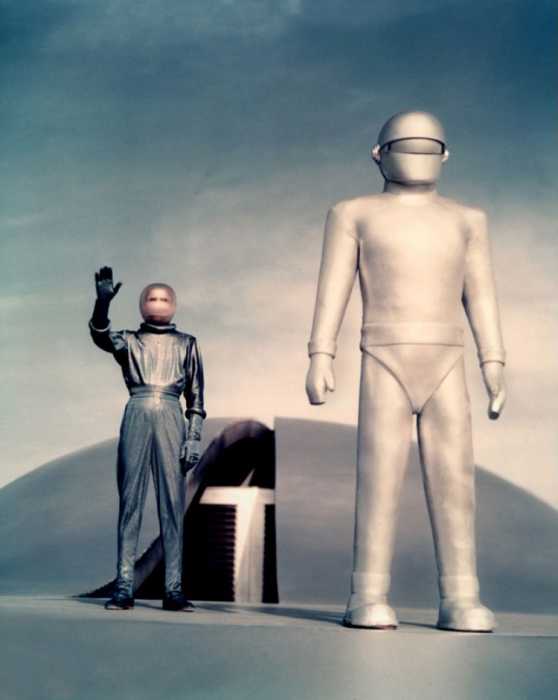

1951. “Klaatu barada nikto”

The height of the Cold War between America and the Soviet Union gave rise to simmering science-fiction drama – far from the fanciful extravagance of Buck Rogers et al, Hollywood delved into the “serious” side of the genre and gave us one of the all-time heavyweights: The Day The Earth Stood Still. In this film, the alien arrival of indestructible Gort and his humanoid master, Klaatu, triggered something of a power-shift in global order, the alien visitor telling Earth that their warlike ways and self-destructive path had brought them to the brink of ruin, and that were they to continue on that way then they would have no future in the universe. The vast power at the alien’s disposal, and his unwillingness to use it in spite of aggressive US military posturing, runs counter to ubiquitous American Might Is Right mantra filling audiences of the day. Even today (in spite of its very average remake), The Day The Earth Stood Still is as captivating and relevant as it was fifty years ago.

The height of the Cold War between America and the Soviet Union gave rise to simmering science-fiction drama – far from the fanciful extravagance of Buck Rogers et al, Hollywood delved into the “serious” side of the genre and gave us one of the all-time heavyweights: The Day The Earth Stood Still. In this film, the alien arrival of indestructible Gort and his humanoid master, Klaatu, triggered something of a power-shift in global order, the alien visitor telling Earth that their warlike ways and self-destructive path had brought them to the brink of ruin, and that were they to continue on that way then they would have no future in the universe. The vast power at the alien’s disposal, and his unwillingness to use it in spite of aggressive US military posturing, runs counter to ubiquitous American Might Is Right mantra filling audiences of the day. Even today (in spite of its very average remake), The Day The Earth Stood Still is as captivating and relevant as it was fifty years ago.

Also in 1951: MGM’s mega-budget film Quo Vadis came out – not only was it the highest earning film of the year, it boasted the record for number of costumes used, and gave Sophia Loren her first film role, in a bit-part as a slave girl – as did Disney’s Alice in Wonderland, the Marlon Brando-starring A Streetcar Named Desire, Humphrey Bogart’s Oscar-winning film African Queen, and George Stevens’ A Place In The Sun. Winning the Oscar for Best Picture was MGM’s An American In Paris, starring Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron, while Bogart would win Best Actor, and Vivian Leigh Best Actress, for Streetcar. In studio news, Columbia Pictures birthed a new studio to combat the rise of television, Screen Gems, while Louis B Mayer, one of the men who founded MGM, was forced to resign by controlling interests in the studio.

1952. Cinerama.

If you’re a fan of cinema in any sense you’d be aware of the fight against television by cinema studios in Hollywood during the 50’s. One of the biggest innovations of cinema was the creation of “widescreen” aspect ratios, in which the film stocks could be used to peripheral-vision filling effect that television simply couldn’t replicate. With wider and wider aspect ratios being used, the widest of them all was Cinerama, a three-camera system whereby a nearly 146° screen could be used to “wrap” around the audience and pull them into the film.  However, the technological limitations of Cinerama were apparent – often prohibitively expensive to shoot, given three cameras affixed to a special rig were needed (basically, tripling the budget of film stock, cameramen, and all the flow-on effects) and limited to very few cinema houses able to display the films themselves, with the enormous demands of both space and cost – and it remained a niche market. Yet the idea of super-wide films became popularised during the 50’s and 60’s, continuing into the modern day with Quentin Tarantino’s use of the the 70mm ultra-wide format for The Hateful Eight, among others. The first theatrical presentation was This Is Cinerama, however the most enduring example of the format was the lengthy How The West Was Won, which is now available in HD formats.

However, the technological limitations of Cinerama were apparent – often prohibitively expensive to shoot, given three cameras affixed to a special rig were needed (basically, tripling the budget of film stock, cameramen, and all the flow-on effects) and limited to very few cinema houses able to display the films themselves, with the enormous demands of both space and cost – and it remained a niche market. Yet the idea of super-wide films became popularised during the 50’s and 60’s, continuing into the modern day with Quentin Tarantino’s use of the the 70mm ultra-wide format for The Hateful Eight, among others. The first theatrical presentation was This Is Cinerama, however the most enduring example of the format was the lengthy How The West Was Won, which is now available in HD formats.

Also in 1952: Major films to release this year include Singin’ In The Rain, arguably the greatest musical ever made, Danny Kaye’s Hans Christian Anderson, Aussie expat Robert Taylor’s Ivanhoe, and ultimate multi-Academy Award winner High Noon, probably one of the most famous Westerns made during the 50’s, if not ever. Charlie Chaplin’s final US-produced film, Limelight, arrived, before Chaplin had a falling-out with the US Immigration Department (Chaplin was a British national residing in the US) and spent the rest of his life living in Switzerland, where he died in 1977. 1952 also saw the passing of screen legends John Garfield (aged 47, following a heart attack attributed to the stress of appearing at the House UnAmerican Activites Committee), the Three Stooges Curly, and Gone With The Wind’s Hattie McDaniel, while John Goodman, Robert Zemeckis, Christopher Reeve and Jeff Goldblum were all born in this year. Cecil B DeMille’s circus epic The Greatest Show On Earth would scoop Best Picture at the Oscars, as well as being the top box-office earner of the year, while John Ford snagged Best Director for The Quiet Man, and Gary Cooper and Shirley Booth garnered Best Actor and Actress that year.

1953. 3D Horror

Given the prevalence of quality films released in 1953, many of which remain iconic classics that have endured significantly, it was Warner Bros 3D horror film House Of Wax, which jagged my attention. House Of Wax is notable not just for being Warner’s first foray into the format, but it was also the first 3D film to feature a stereo soundtrack, and marked the debut of screen horror icon Vincent Price, who would go on to become a legend aligned with Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing. Although Columbia released the first 3D film, Warner’s release remains the most enduring and has since become a cult classic.

Also in 1953: Look, it’s fair to suggest 1953 ranks alongside 1938 as one of the Hollywood great periods. From Here To Eternity would snag Best Picture and Director at the Oscars, and would become the year’s second-highest earner after the first ever anamorphic widescreen film, The Robe, starring Richard Burton and Jean Simmons. Marilyn Monroe captured the zeitgeist in both How To Marry A Millionaire and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (from which we get “Diamonds Are A Girl’s Best Friend”), while Shane became a classic of the Western genre, and Disney bowed what would become the definitive version of Peter Pan, to great acclaim. Marlon Brando’s popular biker movie, The Wild One, arrived in cinemas, while William Holden would win his only Best Actor Oscar following his performance in Billy Wilder’s thrilling Stalag 17.

1954. Gojira

Arguably the most famous of all big-screen monsters, Gojira (aka Godzilla) debuted in Japan and with it came countless sequels and spin-offs, a gaggle of similarly themed monster creations including Mothra (a giant moth), Ghidorah and robotic arch-nemesis MechaGodzilla. Godzilla came along partially as an answer to Hollywood’s King Kong (which had recently gained attention following re-release) and similarly-plotted American film The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, released in 1953. Godzilla’s arrival was popularised as analogous to the frightening nuclear scenarios the Japanese people were fearful of, and has become somewhat synonymous with Japanese culture through its ubiquity in modern cinema. The franchise was coerced by Sony Pictures in their disappointing 1997 attempt to American-ise the brand, with Toyo Pictures (the Japanese owners of the franchise) famously refusing to allow Hollywood to have another shot – until 2014’s better-received effort came along. It has since become the metonym for giant-monster films, and remains the longest still-running film series on the planet.

Also in 1954: Kurosawa released The Seven Samurai, arguably the greatest Japanese film ever made, Hitchcock’s Rear Window became the year’s highest earner, while searing drama On The Waterfront would scoop Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor and Best Supporting Actress at the Academy Awards, and legendary credit designer Saul Bass would start his career with Carmen Jones. Dragnet became the first feature film to be derived from a television series (something pretty familiar to us all today!), while ubiquitous seasonal favourite, Big Crosby’s White Christmas, would debut (also marking the first use of Paramount’s VistaVision widescreen process), and The Caine Mutiny, Sabrina (starring Humphrey Bogart and Audrey Hepburn), Vera Cruz and 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea (with Kirk Douglas and James Mason) landed in cinemas. Passing away in 1954 were accomplished British actor Sydney Greenstreet (Casablanca and The Maltese Falcon) and Lionel Barrymore (It’s A Wonderful Life, Key Largo and Grand Hotel), while we saw the debuts of Jack Lemmon (in It Should Happen To You) and Paul Newman (The Silver Chalice).

1955. A Rebel Dies

Hollywood is littered with the tragedy of stars passing well before their time (case in point, Heath Ledger), but none have reached the hallowed status of that of James Dean’s 1955 death in a car accident. Having only three films to his credit – one of which, Giant, would be released posthumously – Dean’s death at aged only 25 captured the imagination of fans thanks to his rebellious, often insolent teenage archetype portrayals in his only other films, East of Eden and the one for which he’s most closely identified, Rebel Without A Cause. Directed by Nicholas Ray, Rebel Without A Cause was a controversial look at the widening gap between generations, with the rebellious youth portrayed by Dean butting heads with the authoritarian, somewhat puritanical adults of the movie. Although somewhat tame by today’s standards, the film epitomised everything the post-war generation was feeling about modern America and became something of a touchstone for audiences keen to associate with its messages and themes. Released a month after Dean’s death, Rebel Without A Cause became a piece of iconic Americana, making stars of Dean, Natalie Wood and Sal Mineo, and forever cementing its aesthetic into the pop-culture zeitgeist.

Hollywood is littered with the tragedy of stars passing well before their time (case in point, Heath Ledger), but none have reached the hallowed status of that of James Dean’s 1955 death in a car accident. Having only three films to his credit – one of which, Giant, would be released posthumously – Dean’s death at aged only 25 captured the imagination of fans thanks to his rebellious, often insolent teenage archetype portrayals in his only other films, East of Eden and the one for which he’s most closely identified, Rebel Without A Cause. Directed by Nicholas Ray, Rebel Without A Cause was a controversial look at the widening gap between generations, with the rebellious youth portrayed by Dean butting heads with the authoritarian, somewhat puritanical adults of the movie. Although somewhat tame by today’s standards, the film epitomised everything the post-war generation was feeling about modern America and became something of a touchstone for audiences keen to associate with its messages and themes. Released a month after Dean’s death, Rebel Without A Cause became a piece of iconic Americana, making stars of Dean, Natalie Wood and Sal Mineo, and forever cementing its aesthetic into the pop-culture zeitgeist.

Also in 1955: Marty would win Best Picture, Best Director (Delbert Mann) and Best Actor (Ernest Borgnine) at the Academy Awards, while East of Eden picked up the major gong at the Golden Globes. Marilyn Monroe’s iconic pose above the New York subway grating would enter pop-culture folklore in The Seven Year Itch, directed by Billy Wilder, Disney released Lady & The Tramp, while memorable films Ain’t Misbehavin’, John Wayne’s Blood Alley, The Dambusters, Les Diaboliques (aka The Devils), It Came From Beneath The Sea, Otto Preminger’s searing drug film The Man With The Golden Arm (starring Frank Sinatra as a heroin addict), The Quatermass Xperiment and Clark Gable’s The Tall Men all arrived this year. Chuck Jones’ acclaimed Warner Bros short, One Froggy Evening, debuted, while Mighty Mouse’s original theatrical run concluded after 13 years. In technical news, the new widescreen 70mm format Todd-AO debuted in Rogers & Hammersteins Oklahoma!, directed by Fred Zimmerman. Clint Eastwood fans will also note 1955 marked the actor’s big screen arrival in a bit-role in low-budget horror flick Revenge of The Creature.

1956. The King arrives.

In the late 50’s and sixties, there was no greater star on planet Earth than Elvis Presley. Launching into the stratosphere with his physicality, sexuality and raw screen presence, Elvis’s humble origins gave way to a monolithic juggernaut of touring, film and television appearances, and recording. One of the highest selling recording artists of all time, and continually referenced as a legitimate pop-culture icon, Elvis’s first film – Love Me Tender – debuted in 1956. It’s notable for two distinct reasons; it was the only time Elvis wouldn’t have top billing (his co-stars, Richard Egan and Debra Paget came in above him) and it was the only film in which his character in the story died. Elvis Presley appeared in no fewer than 30 dramatic films – all but a handful being musicals – between 1956 and 1969, when his star began to fade, but Love Me Tender remains among his most low-key and most approachable. As a combination threat of singing, dancing and acting (although some have said that Presley’s acting was the weakest part of his game) there’s little doubt his success was derived solely due to his singing ability and looks, and little else. His films are by-and-large forgettable fluff, cookie-cutter productions designed to showcase the singer’s latest hit singles, and dangle a pretty young starlet off his arm, but they made enormous bank in their day and for that it’s hard to look past the singer-as-an-actor screen dynamism that was the King of Rock And Roll.

In the late 50’s and sixties, there was no greater star on planet Earth than Elvis Presley. Launching into the stratosphere with his physicality, sexuality and raw screen presence, Elvis’s humble origins gave way to a monolithic juggernaut of touring, film and television appearances, and recording. One of the highest selling recording artists of all time, and continually referenced as a legitimate pop-culture icon, Elvis’s first film – Love Me Tender – debuted in 1956. It’s notable for two distinct reasons; it was the only time Elvis wouldn’t have top billing (his co-stars, Richard Egan and Debra Paget came in above him) and it was the only film in which his character in the story died. Elvis Presley appeared in no fewer than 30 dramatic films – all but a handful being musicals – between 1956 and 1969, when his star began to fade, but Love Me Tender remains among his most low-key and most approachable. As a combination threat of singing, dancing and acting (although some have said that Presley’s acting was the weakest part of his game) there’s little doubt his success was derived solely due to his singing ability and looks, and little else. His films are by-and-large forgettable fluff, cookie-cutter productions designed to showcase the singer’s latest hit singles, and dangle a pretty young starlet off his arm, but they made enormous bank in their day and for that it’s hard to look past the singer-as-an-actor screen dynamism that was the King of Rock And Roll.

Also in 1956: Epic films became the order of the day for cinema patrons in the mid 50’s, with the year’s highest box-office earners being DeMille’s The Ten Commandments, Michael Anderson’s Around The World In 80 Days, and James Dean’s final film appearance, Giant. Audrey Hepburn would star in War & Peace, Deborah Kerr and Yul Brynner burned up the screen in The King and I, and John Wayne cemented his cinematic legacy with one of his best films, The Searchers. Incidentally, Around The World in 80 Days would snag Best Picture at the Oscars and Golden Globes, while Yul Brynner would grab Best Actor, and Ingrid Bergman the gong for Best Actress (in Anastasia) for that year. The Americanized version of Gojira (retitled Godzilla), starring Raymond Burr in a haphazardly edited and re-shot edition, launched in America (to what acclaim, I’m unsure), while the beautiful Grace Kelly, star of such films as High Noon, To Catch A Thief and Rear Window, married Prince Ranier of Monaco and promptly retired from acting. Two classic sci-fi films arrived: Forbidden Planet (a personal favourite) and Invasion Of The Body Snatchers, while The Wizard Of Oz debuted on US network television in a blaze of publicity – and has remained so for generations. Other notable films released in 1956 include The Court Jester, starring Danny Kaye, High Society, starring Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra and Grace Kelly in her final film role, one of the great French films The Red Balloon, while we mourned the passing of Bela Lugosi in August aged 73, Robert Newton and George Bancroft.

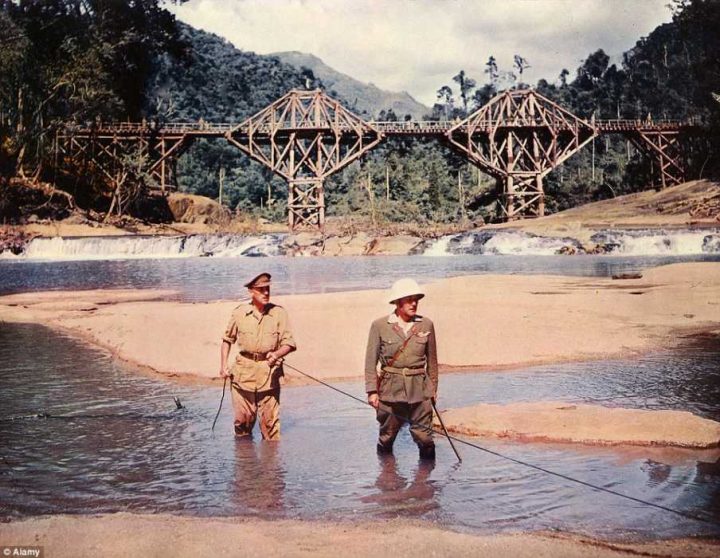

1957. That Damned Bridge

Dominating the film landscape in 1957 was one of Hollywood’s greatest war films, The Bridge On The River Kwai. Boasting an exceptional cast, including eventual Best Actor Oscar winner Alec Guinness, William Holden, Jack Hawkins and James Donald, and directed by the legendary David Lean, The Bridge On The River Kwai swept all before it at the major award ceremonies and became the highest box-office earner of the year. Shot in ultra-wide Cinemascope on location in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), the film is a remarkable piece of filmed entertainment and dramatic narrative set during World War II and depicting Japanese POW camps at their height. On a budget of $US2m, the film recouped some $30m in ticket sales, and is now regarded by many as one of the great films of all time.

Dominating the film landscape in 1957 was one of Hollywood’s greatest war films, The Bridge On The River Kwai. Boasting an exceptional cast, including eventual Best Actor Oscar winner Alec Guinness, William Holden, Jack Hawkins and James Donald, and directed by the legendary David Lean, The Bridge On The River Kwai swept all before it at the major award ceremonies and became the highest box-office earner of the year. Shot in ultra-wide Cinemascope on location in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), the film is a remarkable piece of filmed entertainment and dramatic narrative set during World War II and depicting Japanese POW camps at their height. On a budget of $US2m, the film recouped some $30m in ticket sales, and is now regarded by many as one of the great films of all time.

Also in 1957: RKO Studios, the name behind Hollywood icons King Kong and Citizen Kane, is sold off by owner Howard Hughes with debts totalling some $20m. With the film library sold to Universal Pictures to distribute, and the rest of the company purchased by General Tire and Rubber Corporation, RKO ceased to exist in 1957. Following their breakup the previous year, Jerry Lewis’ first solo film without Dean Martin, 1957’s The Delicate Delinquent, saw a changing of the comedian’s fortunes away from his long-time double act. Humphrey Bogart, considered one of the industry’s biggest stars, died of throat cancer, aged just 57, while Swedish director Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal arrived in cinemas and polarised audiences everywhere. Hammer Studios released the first colour film featuring Frankenstein (the first in their ongoing horror series starring the legendary monsters), and Island In The Sun courted controversy by depicting several interracial relationships. This year we also saw the passing of Oliver Hardy (of Laurel and Hardy fame) aged 65, The Band Wagon’s Jack Buchanan, and Hollywood studio executive and producer Louis B Mayer.

1958. Musical Twilight.

Movie musicals were waning in popularity by the end of the 50’s, as audiences sought entertainment in more dramatic fare, but the genre wasn’t going down without a fight. Gigi, the last of the MGM Musicals from the Golden Age of Hollywood, broke the record at that year’s Academy Awards, snagging all nine gongs for which is was nominated (notably, not a single acting award among them), including Best Picture, Director (Vincente Minnelli, who had also helmed The Band Wagon starring Fred Astaire), Cinematography (Joseph Ruttenberg), Adapted Screenplay (Alan Lerner) and Original Score (Andre Previn). Although it became the biggest Oscar winner ever, it would hold the record for only a single year, with the mighty Ben Hur arriving the following season. Starring Leslie Caron, Louis Jourdan and Maurice Chevalier, Gigi set the template for a new musical era in which song and dance furthered the narrative rather than interrupted it, and prolonged dramatic interludes rather than obfuscating them.

Also in 1958: one of Hitchcock’s greatest films, Vertigo, arrived with a critical thud. Although not noted at the time for much aside from being the first film to use the dolly-rack-zoom effects (to achieve the sense of vertigo, natch), it has since gone on to become considered not only one of Hitch’s best projects, but one of the greatest films ever made, period. South Pacific became the year’s highest domestic earner, Elizabeth Taylor and Paul Newman steamed up the screen with Cat On A Hot Tin Roof, Orson Welles’ technical prowess launched high with Touch of Evil, the World’s Fair in Brussels voted Battleship Potemkin the “greatest film of all time”, while schlock film director-producer William Castle promoted his latest film, Macabre, by offering audience members free funerals via a $1000 insurance policy for people who died watching it. David Niven (Separate Tables) and Susan Hayward (I Want To Live) would snag Best Actor and Actress Oscars, The Defiant Ones won Best Drama Film at the Golden Globes (Gigi won Best Musical), while Hollywood mourned the passing of Robert Donat (Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps), Tyrone Power (The Mark of Zorro) and producer Mike Todd (Around The World In 80 Days). Also of note: the one and only Bugs Bunny cartoon to ever win an Oscar, Knighty Knight Bugs, debuted in 1958.

1959. None Bigger Than Ben.

They truly don’t come much bigger than 1959. While many consider 1939 one of the greatest years in Hollywood’s history, I’m inclined to hold up 1959 as an equal to that in terms of sheer spectacle and output. None moreso than eventual 11-Oscar-winning Ben Hur, the staggeringly mounted Charlton Heston biblical epic that became the yardstick by which all films are measured. Ben Hur’s achievements in both production, writing and acting are legendary, and rightly so, with the film’s superlative achievements remaining immediately iconic to this very day. The film boasted one of the widest aspect ratios ever used in a single-camera film (approximately a 2.77:1 ratio), and one of the most exciting action sequences ever filmed to that point: the almighty chariot race, a ten minute sequence that gave rise to several legends of the film’s longevity and prominence in Hollywood’s mythology. Heston’s performance is career-best, William Wyler’s direction handsome, energetic and borderline perfection, and the film’s box-office toppling all but Gone With The Wind in terms of ticket sales to that point, Ben Hur is the very pinnacle of one of Hollywood’s golden years of production.

They truly don’t come much bigger than 1959. While many consider 1939 one of the greatest years in Hollywood’s history, I’m inclined to hold up 1959 as an equal to that in terms of sheer spectacle and output. None moreso than eventual 11-Oscar-winning Ben Hur, the staggeringly mounted Charlton Heston biblical epic that became the yardstick by which all films are measured. Ben Hur’s achievements in both production, writing and acting are legendary, and rightly so, with the film’s superlative achievements remaining immediately iconic to this very day. The film boasted one of the widest aspect ratios ever used in a single-camera film (approximately a 2.77:1 ratio), and one of the most exciting action sequences ever filmed to that point: the almighty chariot race, a ten minute sequence that gave rise to several legends of the film’s longevity and prominence in Hollywood’s mythology. Heston’s performance is career-best, William Wyler’s direction handsome, energetic and borderline perfection, and the film’s box-office toppling all but Gone With The Wind in terms of ticket sales to that point, Ben Hur is the very pinnacle of one of Hollywood’s golden years of production.

Also in 1959: Hmm, let’s see. Hitchcock’s North by Northwest. Billy Wilder’s Some Like It Hot (starring Marilyn Monroe). Howard Hawk’s John Wayne epic Rio Bravo. Otto Preminger’s Anatomy Of A Murder. Stanley Kramer’s post-apocalyptic drama On The Beach (starring Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner and Fred Astaire). George Stevens’ The Diary of Anne Frank. Hammer horror The Mummy, starring Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee. The roll-call of superb films continues 1959’s run as one of the great dramatic years in cinema. Hollywood mourned Cecil B DeMille, Lou Costello (of Abbott and Costello), Raymond Chandler, Errol Flynn and director Edmund Goulding (Grand Hotel), while we note the screen debuts of James Couburn, Martin Landau and George C Scott, among others. A young Stanley Kubrick would be called up to complete directing Spartacus (released in 1960) after producer and star Kirk Douglas fired original helmer Anthony Mann, William Castle again produced a bizarre promotional idea for a film – his thriller The Tingler had auditorium seats outfitted with tiny motors beneath the base that buzzed audiences at moments during the film – and Walt Disney released Sleeping Beauty to considerable acclaim. Rounding out the decade, the comedy troupe The Three Stooges made their 190th and final short film, entitled Sappy Bull Fighters, and Marlon Brando became the first actor to score a $1m payday for a single role, in The Fugitive Kind.

LOL what's wrong with bloody Hollywood musicals tho? he he he.

I think the 50's represented a glacial change in cinema (in America, not the rest of the world) and it wasn't until the 60's, and things like the sexual revolution, civil rights and Vietnam came along and ruptured the Good Old America trope to prevalent in the day. This is a generalisation, though, and hardly specific. The style of film between, say 1951 and 1959 tended to remain fixed in a steady, workmanlike style without offering anything game-changing, at least overall. Sure, some films came along and captured lightning in a bottle here and there (check out Sinatra in The Man With The Golden Arm, a film so on-topic about drug use it's actually shocking, as an example) but the overall rigidity and inability of 50's Hollywood to really explore their potential is a bit of a let-down.

Admittedly, films like Ben Hur and Cleopatra and Kwai and Godzilla became classics due to their scope or size or visual dynamism, but to my mind they were the exceptions that proved my point. Without giving things away, easily the most profound shifts in cinema of the post-war era (again, in my opinion) were the 60's and the 90's. I'm not that knowledgeable on 50's cinema, though, so take that with a grain of salt. 😉

A wonderful series continues. Detailed and informative read, Rodney. It seemed like such a transformation in style and content in the 1950s. It must have been a great time to experience cinema and its its progression during the period. When I think of the 1950s I think of Hitchcock's heyday rather than the historical epics (it would also appear than many of my favourite arrived in 1959). If I had been around back then I would have certainly welcomed the decrease in those bloody Hollywood musicals though.

My recent post “Suicide Squad”: The World Of The Antihero Has Rarely Been This Much Fun

So much information. I think my head exploded while reading this…in a good way, of course. These posts are fantastic. I especially loved the write-up on Gojira, which I don't think I've seen. Well, I have seen the American version, just can't remember if I saw the original Japanese version. Side note: The Day the Earth Stood Still was born out of much the same fear with what happened in Hiroshima pretty fresh on everyone's minds, not just the Japanese. By the way, you were far too kind to its remake. The remake is so far below average, it's not even funny.

I got to watch a movie (a really dry doc on the universe) in a planetarium today with the picture taking up the entire inside of the dome. I imagine seeing a film in cinerama must have been a similar experience. The whole time I was watching it, I kept remarking to myself how great it must be to watch a good movie on that thing. Said all that to say I would love to have seen something in cinerama with today's technology. Could be a couple steps ahead of IMAX.

The tidbit on William Castle offering free funerals might be the greatest thing I've ever learned. This dude is PT Barnum to the nth power.

And I still need to see a James Dean flick. Sigh.

Looking forward to the next one of these.

My recent post Thursday Movie Picks: Gambling

I think many modern directors could learn a thing or two from William Castle – offering free funerals to people bored to death during their films might be the way to go! LOL

I saw the original Gojira on Blu a few weeks back (Criterion offer a stellar HD version) and was amazed at what the Japanese were allowed to get away with in terms of narrative and spectacle. I have not seen the US-version of this film (with Raymond Burr) but I hear tell it's abysmal, so I guess I'll have to see it for shitz-n-giggles!

Glad you're enjoying these, mate! They've been really great putting together!

Another fantastic post, Rodney. I really enjoy reading these. I have to say that, so far, the 1950s is the most disappointing in terms of industry output. The only truly great film on the list is Seven Samurai. The rest of them might be OK or even downright bland. I think the 50s were more gimmicky than anything else.

Oh, and Bridge on the River Kwai "as one of the great films of all time," was a hilarious line. You crack me up sometimes.

LOL thanks man. I recalled your (less enthusiastic) review on BOTRK and I had to smile as I wrote this. I haven't officially review the film here, but I think it's a terrific piece of propagandist heroism (whether it's cliched or outdated, I guess is subjective) and stands the test of time – at the very least, it's a showcase for Alec Guinness's fantastic work.

The 50's films are tough nuts to crack, I guess. Many of them conform to that regimented, oft-rigid American social uprightness that comes with the suit-n-hat brigade depicted in the dramatic films of the era. They can be impenetrable to a degree, I agree, but I think closer retrospective inspection and examination can lead to an appreciation of thematic material that seems visually staid and boring but stimulates the intellect with terrific effect.

Phenomenal post. Personally I still maintain that the best decade for cinema was the 50s. The sheer number of great movies, budding stars, and bold new film movements. And the sheer variety that popped up during those years. Amazing.

As I've researched these posts it's become obvious to me that each year/decade is stuffed full of cinematic gems (and a fair amount of turkeys, it must also be said). It's hard to really get a handle on which period of Hollywood's history has produced the most creatively successful output – the silent era films arguably had the toughest job because the actors had to emote *without* dialogue to aide them, while the more recent eras had the benefit of bigger and better technology and visual effect capabilities to draw on, in order to tell the story. I think for a sheer explosion of different forms of cinema, it's hard to go past the post-war 40's and 50's, with the exposure of European films and subcontinent Bollywood stuff just going gangbusters in what we might call "mainstream" box-office, as well as different styles and genre's being introduced.

It's been interesting thus far, at least.