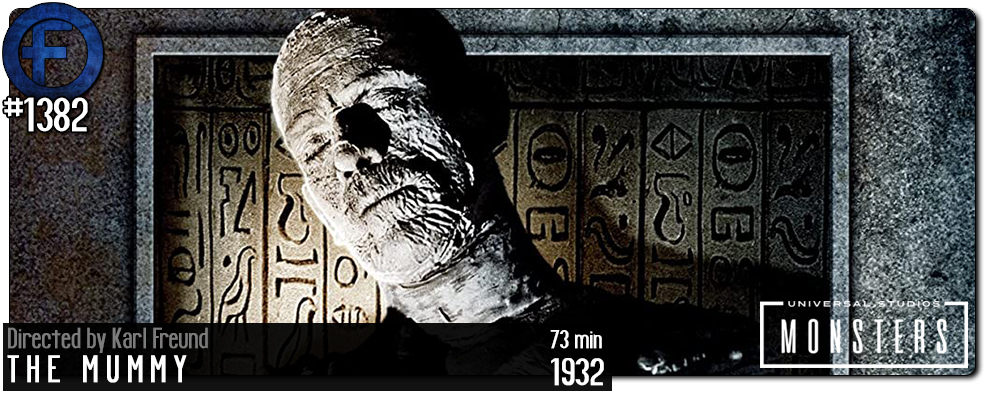

Movie Review – Mummy, The (1932)

Principal Cast : Boris Karloff, Zita Johann, David Manners, Arthur Byron, Edward Van Sloan, Bramwell Fletcher, Noble Johnson, Katheryn Byron, Leonard Mudie.

Synopsis: A living mummy stalks the beautiful woman he believes is the reincarnation of his lover.

******

Basically, when something warns you not to open it on pain of eternal damnation, you better obey. 1932’s The Mummy cemented Universal as a cinematic horror powerhouse, following the smashing success of Frankenstein and Dracula the previous year. It also catapulted star Boris Karloff, responsible for bringing the monster of Frankenstein to life and appearing as Ardeth Bay and the Mummy, into a full-fledged Hollywood icon. Eminently atmospheric, creepy and imaginative, director Karl Freund (who had worked as cinematographer on Dracula, as well as Fritz Lang’s Metropolis) gives the film an understated feel of decrepit ageing – suitable to its star’s dusty history – and the story of supernatural history works its well as a slow-burn chiller.

Karloff plays ancient Egyptian priest Imhotep, brought back to life following his tomb’s exhumation during a British expedition to the region in 1921. Led by Sir Joseph Whemple (Arthur Byron) and Dr Muller (Edward van Sloan), a mysterious box opened by the expedition’s associate Ralph Norton (Bramwell Fletcher) unleashes a curse upon him, returning the long-dead mummy to life, and searching for his one true love, Princess Ankh-es-en-Amon, who he believes has been reincarnated in the form of Helen Grosvenor (Zita Johann). Whemple’s son, Frank (David Manners), assists in protecting Helen from the clutches of Imhotep, now disguised as elderly Egyptian seer Ardath Bay.

In almost every way, The Mummy is at its heart a tragic love story. Imhotep, whose love for Ankh-as-en-Amon known not even the boundary of death, will stop at nothing to bring his dead lover back to life, even if it means the lives of innocents around him. It’s this inherent sadness about the character than endears him as a truly remarkable villain: Karloff, who spends more time in the aged make-up of sinister Ardeth Bay than he does as the enwrapped corpse of the poster, brings a quiet gravitas to the role, his eerie British accent and magnificent make-up (thanks to resident Universal make-up artist Jack Pierce) affording the film an underplayed creepiness that no amount of modern technology has adequately replicated. The story dabbles in the supernatural, Egyptian mythology and stiff-upper-lip British superiority, combining to develop the spooky sense of danger from Imhotep’s insistent desires. The film doesn’t dwell on salacious violence or sexuality, as established in Frankenstein and Dracula, but rather an intellectual horror drawn from the audience’s imagination instead of anything specifically visual.

While Karloff himself makes a compelling leading actor, with his deep baritone, gaunt set-back eyes and towering frame, he’s ably assisted by a roster of supporting actors including David Manners, as the film’s romantic third-wheel, and Universal regular Arthur Byron as Frank’s father (and instigator of the whole thing), who understand the supernatural elements enough to provide the film’s exposition. Leading lady Zita Johann is utterly luminous as Helen, the apparent reincarnation of Imhotep’s long-dead lover – the film cavorts with glimpses of skin in its final act scenes, as Johann is garbed in “traditional” Hollywood-ised Egyptian costuming including a rather flimsy bikini top. The characters aren’t particularly well developed, but offer enough depth to justify enjoying their arcs throughout the movie, as shallow as they are. The romance between Manners’ Frank and Johann’s Helen is as brisk as cinema would allow back then – at one point, Frank utters the line “I will make you love me” so you know when this film was made – and the softly-spoken malevolence of Karloff’s Imhotep lures her to almost certain doom.

The film’s potency is derived largely from its atmospheric visuals, crisp black and white photography of the period and some stunning lighting. Technically, the film is superbly directed, from its cinematography (by DOP Charles Stumar) to costuming and editing, as well as a haunting musical accompaniment. The use of lighting to cast shadows deep into the film’s frame, as well as highlighting Karloff’s pronounced visage and co-star Johann’s glorious radiance, is an achievement in and of itself, whilst the studio-bound sets are cavernous and gorgeous.

As an early horror film, The Mummy is a masterclass in filmmaking. Resoundingly iconic, deservedly so, The Mummy’s frightening lure is derived from a lack of understanding about Egyptian lore by casual audiences who find the embalming and interment of corpses during ancient times to be subliminally horrific anyway, which makes the character’s return from the dead even more sinister. Gratifyingly stylish and refreshingly restrained, The Mummy’s dusty motif and degenerative title character stand the test of time as an outright cinematic classic and the benchmark for films bearing its appellation.