Movie Review – Shawshank Redemption, The

Director : Frank Darabont

Year Of Release : 1994

Principal Cast : Tim Robbins, Morgan Freeman, Bob Gunton, William Sadler, Clancy Brown, Gil Bellows, James Whitmore, Mark Rolston, Jeffrey DeMunn.

Approx Running Time : 142 Minutes

Synopsis: Two imprisoned men bond over a number of years, finding solace and eventual redemption through acts of common decency.

*******

Few films have found near mythical endurance since their theatrical debut as that afforded The Shawshank Redemption. The first of what would become a Stephen King adaption one-two punch by Frank Darabont (he would follow this film with The Green Mile), The Shawshank Redemption was surprisingly met with tepid commercial box-office and a lethargic Oscar campaign before it would go on to become regarded as one of the greatest films of all time (according to IMDb), hailed as a masterpiece and a touchstone for 90’s cinema in a manner many films could never hope. Revisiting Shawshank many years later, one finds a film of poetic humanity and heart beneath a veneer of depravity and animalistic dehumanisation, ably captured by Darabont’s sterling direction and a breakout role in Morgan Freeman.

After being found guilty of the murder of his cheating wife and her lover, banker Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins) is sent to Shawshank Prison where he’s to serve out two consecutive life sentences. There he meets fellow inmate Ellis “Red” Redding (Morgan Freeman), with whom he forms a friendship as the years wear on. While he continues to protest his innocence, Andy also encounters young rebel Tommy Williams (Gil Bellows) who can prove Andy’s story, while the cruel prison Warden, Norton (Bob Gunton) maltreats his inmates with a firm and unjust hand. Eventually, the prison comes to realise that Andy can assist them with their taxes (which he does) in return for donations to the prison in the form of books and maintenance and building materials. As the years turn into decades, the poster of Rita Hayworth hanging on Andy’s cell wall turns to that of other famous actresses, including Rachel Welch; it is also around this time that Andy’s thoughts turned to that of escape.

I don’t really recall the first time I ever saw Shawshank. It’s the kind of film that feels like it’s always existed, a modern equivalent to the Golden Age masterpieces of Hollywood’s silent era or the late-30’s pre-war creative height. Revisiting the film on an almost annual basis ever since, the warm nostalgic tones Darabont’s film is infused with wash over me as I take in both the violence and subtle brotherly love between the inmates of the titular prison, and although you could say the film bathes its dreamlike tones with a heady mixture of soft-focused contemplation among the moments of abject violence, never once does the film really feel unreal. Shawshank is the story that could have happened – maybe it did, somewhere, sometime – and Darabont makes us believe in its sense of justification and freedom. While I never really got the themes of humanism and breaking of men’s spirit in King’s original story (I really must re-read it sometime), in the craftsman hands of Darabont’s writing the characters come alive on the screen in a way they simply can’t on the page.

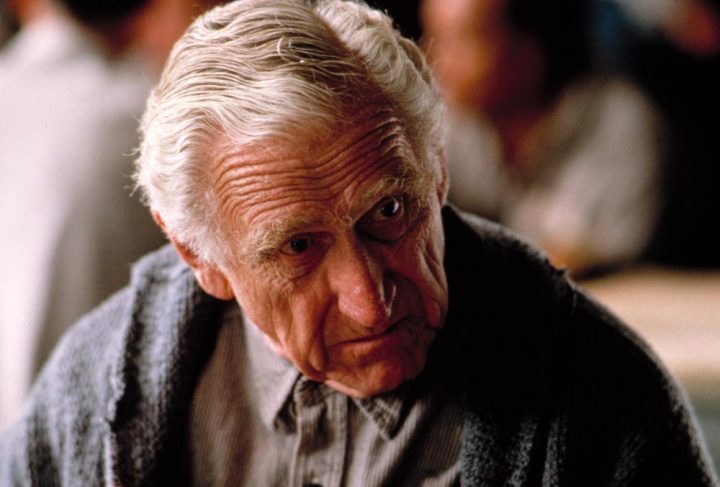

Part of Shawshank’s appeal to me is that it’s a film of simplicity. There’s some twists and turns (the subplot involving Gil Bellows’ and his knowledge of Andy’s innocence is a good one) and several moments of pure joy (the rooftop beer drinking scene, as well as Andy’s playing of a record to inmates across the prison, are two that stick in the mind) which marinate the story of two men seeking redemption (of all things) inside a prison, while among the most memorable side characters is James Whitmore’s tragic Brooks Hatlen, a lifer suddenly freed who cannot handle how the world “went and got itself in a big damn hurry”. Carefully layered into the central tale, Shawshank’s idealised theme of hope, and how prison robs men of that very thing, strikes a chord harder now in this Trump-era American breakdown, as the indifference authority has to those perceived to have broken the law is mirrored in the film’s timeless ideals. Had this film been made fifty or sixty years prior, one might see James Stewart and Sidney Poitier in the leading roles.

Casting plays a crucial role in any film, and Shawshank struck cinematic gold with the choice of Morgan Freeman as Red. Alongside Tim Robbins, Freeman excels in the role, honing his quiet philosophising screen persona with that drawling, dulcet voice. Freeman was coming off a couple of Oscar-nominated performances before he took up Shawshank (Street Smart and Driving Miss Daisy) and as he waxes poetic through Darabont’s sonorous dialogue, he brings a weighty gravitas to the film that few other actors might have achieved. Robbins, for his part, feels uneasy in the role, as if he’s uncertain of his arc, and in recent years I come to consider the actors’ performance here as among the film’s weakest elements – which is saying something considering the esteem in which it’s held. I just don’t think Robbins gives the part enough sass or driven focus to make it work.

Supporting roles to Mark Rolston, as the prison Bull Queer leader, Boggs, as well as Clancy Brown as a vindictive guard and William Sadler as an illiterate, stammering fellow inmate, provide interesting sidebar characters around which Andy congregates, while Bob Gunston’s steely-eyed prison warden remains among the better screen villains of the period. The aforementioned James Whitmore’s performance as Brooks is legitimately one of those moments men are allowed to cry at the movies (damnit, I tear up just thinking about it now), while Gil Bellows’ fresh-faced enthusiasm generates minor interest.

The film captures prison life exceptionally well, albeit with that soft-focused glow. Filmed at a then-working prison in Ohio, the film’s stately grandeur and strong visuals, coupled with exquisite editorial choices and the cast’s brave on-screen performances, make Shawshank as much as visual treat as it is an intellectual one. The film’s cinematographer is the legendary Roger Deakins (True Grit, Skyfall, Sicario) and the use of actual locations where possible added a sense of authenticity to the film it wouldn’t have had on a soundstage. Deakins bathes his actors in soft light and graded shadows, his keen eye nailing the tone of Darabont’s period film and offering one of the most astonishingly beautiful prison films ever captured. Little wonder he snagged an Oscar nomination here. Thomas Newman’s aching score is appropriately thematic, flush with light and shade and the perfect musical accompaniment to the on-screen action.

It might sound like Shawshank is a perfect film; in reality, with the exception of Tim Robbins’ indifferent performance, it is the perfect film. Faultless direction, nearly faultless acting, and production value that clicks together and makes it impossible to consider any alternatives, The Shawshank Redemption’s strength as a story is amplified by Darabont’s strengths as a director. Few film are held in such esteem among the critical fraternity as this one, and even fewer films deserve to be. The Shawshank Redemption is a masterclass in cinema storytelling and one of the great American movies of all time.

You can read our previous article about this film here.