The Big Reveal: Do Modern Film Trailers Show Too Much?

Studios spend hundreds of millions of dollars every year letting us know about their upcoming film projects. Every year they try to lure us into the darkened cineplexes to watch their latest stuff, with everything from major tentpole blockbusters to low-budget indie dramas finding themselves the subject of the one thing nobody can resist watching: the film trailer. Sure, posters and cast interviews and weird websites can offer interest and intrigue as to the quality of a film, but by far the most finely tuned and well honed artform in Hollywood is the release of a film’s trailer.

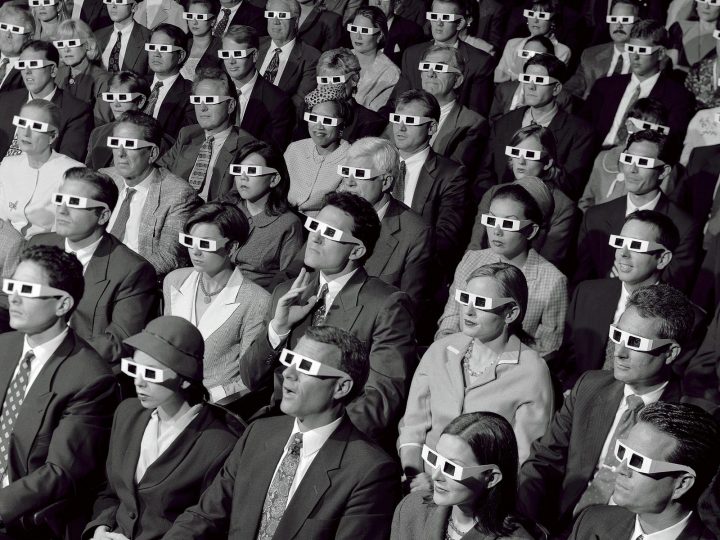

Trailers have been around since cinema was born. Used as a way of marketing upcoming films to audiences, trailers began their lives at the end of a feature presentation, until cinema managers realised most people up and left before they ever saw them. The obvious solution: stick a trailer at the start of the film presentation and maximise eyeballs. As entertainment has expended and our society has shifted into a time-sensitive consumer-driven age, there are increasingly fewer eyes catching the lower budgeted films being made, mainly because marketing budgets are swallowed whole by the saturation-level push of the Big Films like an Avengers, Star Wars, Transformers or Fast & Furious instalment. A film’s trailer is usually the audience’s gateway into a film, a glimpse of a film’s tone, story and characters, a hook for willing viewers to suggest that this film might be worth your time.

Film trailers have become incredibly well honed at giving audiences that hook, yet having to maintain some level of secrecy in order to avoid the dreaded “spoiler”. Some, like the infamous trailer for Robert Zemeckis’ What Lies Beneath, actually reveal a film’s twist to the audience before the film even comes out. Others are more careful about what they show; the marketing for the pre-release of Warner Bros’ Justice League, for example, never so much as gave us a glimpse of Superman, despite foreknowledge that he would return after his apparent death in Batman V Superman. Some films even have specially shot trailers that contain no footage from the finished film whatsoever: Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man had a trailer that showed the film’s hero capturing a helicopter full of criminals between the towers of New York’s World Trade Center, before it was pulled from screens following 9/11. Roland Emmerich’s Godzilla, all the way back in 1996 (a full year before release), had a trailer involving the titular creature’s enormous foot coming down through the roof of New York’s Natural History Museum – a scene nowhere to be found in the film itself.

Today, trailers are an event in and of themselves. Studio’s hype up even trailer releases days and weeks beforehand – Marvel’s anticipated Avengers: Infinity War trailer, which debuted at this year’s ComicCon, eventually screened (in a different edit) online and via terrestrial US Network television last week to enormous fanfare and reception, while each new Star Wars trailer is greeted with the awe and wonder of the second coming of Christ. Studios know these trailers breed enthusiasm for a property which may still be months away – it’s a tap on the shoulder to say “hey, our film is coming out next year, here’s a taste for y’all”.

Most studios are keen to show off the money they’re spending on a film. Trailers often showcase one or two specific scenes that contain a lot of visual effects (if it’s an effects film) or a key dramatic moment to whet an audience’s appetite. You want to see something before you plonk down your hard-earned cash to see a film, knowing that the bigger the budget, the less a film’s script is up to standard. That said, you don’t want to have the film experience spoiled for you by an unrelenting marketing campaign designed to basically grab your pubic hairs and drag you by the groin into the cinema. It makes sense to keep something for the paying audience, a twist or reveal or something special to make actually going to the cinema more valuable than simply waiting for the iTunes version.

This week, the trailer for the latest Jurassic Park sequel, Fallen Kingdom, released to a wave of mediocre reviews. Obviously, the film looks stupidly illogical, but it affords us yet another romp with the genetically reborn dinosaurs we hope will thrill us once again. One of the film’s chief criticism is that it gave away at least one of the film’s major set-pieces: the eruption of a volcano and the flight of not only our heroes but the film’s animal cast into an apparent watery death. Universal aren’t silly: there’s no way they’d blow their film’s climactic moment in the first trailer they release. Director JA Bayona came out and stated that all the footage from the trailer comes from the film’s first hour, obliquely suggesting that “we ain’t seen nothin’ yet”. The argument, however, is that Fallen Kingdom’s debut trailer went too hard too early with showcasing its visual effects and cleverness, tapping into our waning memory of Spielberg’s original classic as we make way for the drab, monochromatic modern style employed by the colour-grading set.

The balance between showing us something worth seeing and keeping the good stuff hidden is a paradox in film marketing. Don’t show enough, and audiences won’t go see your film on the critical opening weekend. Show too much, and audiences leaving the cinema will spread the word that “if you’ve seen the trailer, you’ve seen the film”, which can cause a dramatic downfall in audience numbers among those who follow cinema. With the boom in social media, a tweetstorm or facebook post can be both a wonderful or a terrible thing. And mostly, it begins with a trailer. The current marketing campaigns seem to base themselves on a formula for success: the first trailer is usually just a hint, a glimpse of initial footage (often with minimal effects, showing character and settings), the second trailer might offer us the story hook, expanding on the first trailer, while the third trailer is usually an orgy of the best stuff a studio can bear to show to the audience. Often, it’s these third trailers (and the glut of television spots that follow) that film fans find problematic, because these are usually the ones that give away the most.

For the most part, modern film trailers seem to err on the side of giving away too much (with a few exceptions) and not keeping things from the audience. It’s to be expected: demographics are key to a film’s success and marketing to kids is different than marketing to adults. The trailer for the recent Transformers turd, The Last Knight, showcased the appearance of young Isabela Moner, a child actress who seemed to be a major component of the finished film. Hint, she wasn’t, and director Michael Bay explained that Paramount wanted to market the film to younger audiences as well, and that was their “in”. Demographic pandering at the expense of a film’s quality? Guess it makes financial sense even though it makes little for the story. This kind of bait-and-switch is expected, but thankfully fewer examples of this are found today. Audiences are smarter (I think) than years gone buy, and can smell a turkey coming a mile off. Consequently, studios have to be a lot cleverer than average audiences.

Sometimes, however, they give away the film before anyone’s actually seen it.

What do you think? Do too many trailers ruin the eventual film experience? Are there too many spoilers? Or do you spend you time avoiding trailers so you don’t see any footage? Let us know in the comments below!

Too true! When I see a film now, I have my headphones on and watch Netflix during the trailers because I want to go in as blind as possible.

You know, my mother always told me you could achieve blindness through masturbation. Maybe you should try that instead. 🙂 🙂

Yeah, they definitely reveal way too much and that’s the reason I haven’t watched them for years… Rather go in knowing as little as possible.

Seems to be a common opinion! I’m not averse to a film’s trailer initially, as I’m usually excited to see what a filmmaker has done (particularly to a franchise film) but after the first one I generally avoid them. I’m not, however, afraid of putting them on my site! LOL