Movie Review – Blade Runner (The Final Cut)

Director : Ridley Scott

Year Of Release : 1982

Principal Cast : Harrison Ford, Sean Young, Rutger Hauer, Edward James Olmos, M Emmett Walsh, Daryl Hannah, William Sanderson, Brion James, Joe Turkel, Joanna Cassidy, James Hong, Morgan Paull.

Approx Running Time : 117 Minutes

Synopsis: A blade runner must pursue and try to terminate four replicants who stole a ship in space and have returned to Earth to find their creator.

******

Next to Alien, Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner remains an enduring icon of American sci-fi cinema, perhaps the greatest exponent of “real” sci-fi to ever grace our screens and certainly one of the most discussed. With its multiple iterations both directorial and studio mandated, a charismatic leading performance from Harrison Ford, and a sense of a wider world unexplored off the edges of the frame, Blade Runner’s mystique and mythic nature both as a film and as a story continues to command blogger inches and demand attention from its audience. The film’s premise, based loosely off Philip K Dick’s seminal “Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep?”, is one that permeates deep into the human condition: that is, what makes us human? Our soul, our memories, or something else? And if we were actually machines programmed to think like a human, would we essentially be human?

In Los Angeles of the year 2019 (the future), a sullen former police officer, Deckard (Ford) works as a “blade runner”, locating bioengineered beings known as “replicants” and killing them. He’s brought in to investigate a murderous example (Brion James) whilst at the same time, also testing a unique replicant given human feelings (Sean Young), as well as pursuing the last of a band of escaped replicants by the name of Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) and his associate Pris (Daryl Hannah).

If I’m honest, Blade Runner never struck me as a particularly great piece of dramatic storytelling. The characters (including Ford’s Deckard) are largely indecipherable, the plot a relatively thin juxtaposition of artificial intelligence and humanity and identity, with the only real selling points being the astonishingly detailed production design and Vangelis’ equally astonishing musical score. In short, Blade Runner (to me) has always been a great deal of style over very little actual substance. I never “got” the film, throughout my childhood and into my early film critiquing career. Approaching such a monolithic touchstone for countless fans always gives one pause, lest I somehow get it “wrong”, but I think if anything Blade Runner isn’t a film one paints with a brush of “right” or “wrong” any more than one approaches a work of great renaissance art.

Blade Runner is meant to be an experience of emotional connection on a plane of thought far above simple cinema; I contrast Blade Runner with the similarities to Terrence Malick’s recent films such as Tree Of Life or Voyage of Time, films that defy conventional narrative structure and feel more like visual poems (whether you like them or not isn’t the point, the point is that you have some reaction to it), and to that end if you approach Ridley Scott’s evocative neo-noir opus as if it’s a feeling manipulator rather than an intellectual stimulator (although many fans have drawn a large number of motifs and dialogues from Dick’s underpinning thematic material) you may find yourself engaged with it a lot more.

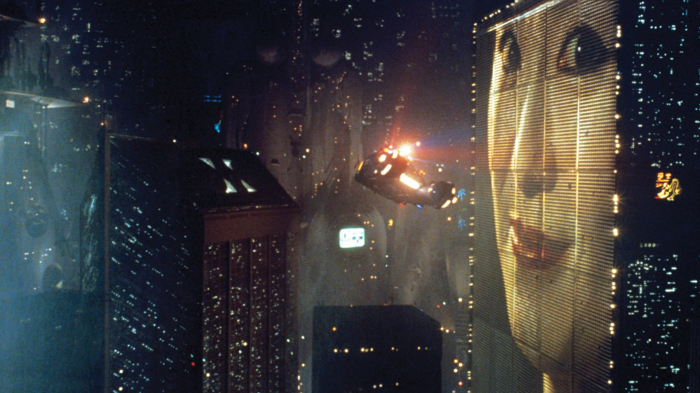

As mentioned, Blade Runner’s chief success is its visual design, both in the hellish nighmarescape of Los Angeles of the “future” and of humanity’s gradual decay approximating Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (a film noted for its depiction of the wealthy elite in the skyscrapers above a seedy, degenerate and violent lower-class population at street-level), as solid a notation on our fixation on class and wealth and luxury as there has ever been. The film feels scorched, almost post-apocalyptic (or at least heading there), with Harrison Ford’s irascible Deckard, who views his existence as meaningless by the time the film opens, transitioning into a figure of hope against the grey prior to the closing credits. Vangelis’ themes and electronic score, pulsating and sonorous and texturally prickling the senses, brings with it a feeling of hopelessness amidst the black, grey and blue of this world.

The script by Hampton Fancher (The Mighty Quinn) and David Peoples (Unforgiven, 12 Monkeys) is largely infused with a pulp sensibility and machismo-laden sexuality. Deckard’s resigned despondence and the laced mystery through the story, as well as his relationship with Sean Young’s Rachel (a progenitor of The Matrix‘s Trinity, in many ways) is never overt, but rather layered on with deft lines of dialogue and plenty of development in costuming and lighting to establish personality. So too, Rutger Hauer’s Roy Batty, a nutball crazy replicant who at one point delivers one of cinema’s most memorable soliloquies about memory and his legacy; Hauer’s eccentricity shines within the character, wild-eyed and prone to fits of violence that, much like his existence, mean nothing to him, and this extreme version of “tech gone bad” makes for a compelling screen villain who has few moral standards. Putting it into a more modern context, Roy Batty is to Blade Runner what Heath Ledger’s Joker was to Nolan’s The Dark Knight: a mechanism of anarchy.

Fans of comic mainstays such as Heavy Metal or Judge Dredd will see a lot of similarities to what Scott and his production team accomplished here. That ubiquitous urban decay, so prominent in science fiction post-Star Wars, is never more omnipresent or oppressive than it is in Blade Runner. The level of detail in Scott’s world-building is mind-boggling, every inch of Jordan Cronenweth’s sublime cinematography filled with things to look at. This isn’t a superficially artificial world, it’s a breathing, functioning organism of shadow, steel and neon, a nightmare version of Tokyo or Hong Kong complete with massive electronic advertising displays and rain-soaked depression. Everything, from set design to costume and effects feels like it exists somewhere, as if Scott stepped into a parallel universe and shot a documentary, it’s that good. Unlike modern films, in which the settings for the film are well lit so you can “see how much work went into making it” at every moment, here the sets and locations bleed off into darkness and sweltering mood, never fully revealing themselves and ensuring the film’s evocative aesthetic is subtle rather than overt. From a technical perspective there’s so much to enjoy here it’s utterly satisfying on so many levels.

Blade Runner is a film you don’t just watch. It’s a film you experience, hopefully on the largest screen with the biggest sound system you can find. It’s also okay not to “get” this film in the fanboy way many do, because it’s not a film made to please everyone, or even be understood by everyone. It’s a film running its own course, a film deep with thematic ideas and philosophies and built primarily on a visual motif of human ruin. It’s also a film that (depending on your version) won’t give you all (or even any) of the answers, because it doesn’t have to. Those expecting a traditional conclusion will find themselves disappointed, and that’s okay. Everyone experiences Blade Runner differently. As I’ve grown more mature in my appreciation of cinema, I’ve come to understand that what Ridley Scott did with this film wasn’t an easy sell to a studio (which is likely why there are so many versions, because if you’re confused imagine how the bean counters and studio executives at Warner Bros felt about it!) and even less of an easy sell to the viewer. Often divisive, always seeking interpretation and analysing, Blade Runner is a film that asks much of the viewer and rewards those open to searching for their own answers.

this is the movie I like the most I’ve ever seen in the 80.

It’s a great film from the 80’s. Have you seen the sequel yet?

I first saw this early on in my time as a full blown movie buff. I didn’t like it. For me, it’s biggest sin was not that I didn’t get it, but that it was paced so poorly it didn’t make me want to get it. It is absolutely gorgeous to look at, no doubt about it. It was just insanely boring. Like you, I’ve become a more mature viewer since then. However, I haven’t gone back to it just yet. I will before I get to 2049. Hopefully, that will be soon. Great write-up, made me more eager to give it another try.

See, I didn’t find the pacing that bad, but i can see how others would. I think it’s a film that grows on you over the years, and it’s definitely not a film you can appraise adequately (or accurately) after a single watch; I urge you to give it another shot and consider it more an exercise in eye candy than a purely dramatic narrative one.