Movie Review – High Noon (1952)

Principal Cast : Gary Cooper, Thomas Mitchell, Lloyd Bridges, Katy Jurado, Grace Kelly, Otto Kruger, Lon Chaney Jr, Ian MacDonald, Eve McVeaugh, Harry Morgan, Morgan Farley, Harry Shannon, Lee Van Cleef, Robert J Wilke, Sheb Wooley.

Synopsis: A town marshal, despite the disagreements of his newlywed bride and the townspeople around him, must face a gang of deadly killers alone at high noon when the gang leader, an outlaw he sent up years ago, arrives on the noon train.

*****

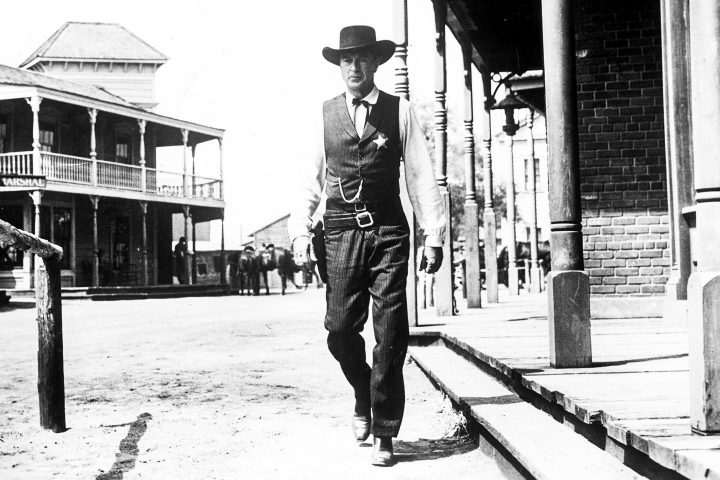

Supercharged American Western High Noon manages to remain scathing in its allegorical stance on McCarthyism of the 1950’s despite the best efforts of time to thwart its power. Gary Cooper is sublime as eponymous town Marshall Will Kane, alongside the fascinating direction of Fred Zinnemann, with its tinderhot politically charged narrative and Oscar-winning score (and original song) among the high points of the film’s lasting legacy. High Noon is also a fantastic example of a film told in “real time”, that is the hour and a half running time plays out the story in a blisteringly taut 90 minutes of Cooper’s pleading with his townsfolk to aide him in his time of need. While it might lack in the “action” department (the final sequence shoot-out notwithstanding) the drama and character byplay here is electric, with co-starring roles to Thomas Mitchell, a young Lloyd Bridges, and Grace Kelly in her big-screen debut, widening the magnifying-glass story with depth and dramatic heft.

Plot synopsis courtesy IMDb: On the day he gets married and hangs up his badge, lawman Will Kane (Cooper) is told that a man he sent to prison years before, Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald), is returning on the noon train to exact his revenge. Having initially decided to leave with his new spouse Amy (Grace Kelly), Will decides he must go back and face Miller. However, when he seeks the help of the townspeople he has protected for so long, they turn their backs on him. It seems Kane may have to face Miller alone, as well as the rest of Miller’s gang, who are waiting for him at the station…

In many respects, High Noon is something of an anti-Western, a progenitor of Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven, in that it depicts a flawed hero beset with a suicide mission while former friends turn their backs on him like dominos falling to fear. Cooper, himself a veteran of the screen by the time High Noon arrived in 1952, essays the grim-jawed, proud and resolutely stoic Will Kane with strength and soulfulness that translates across the years between then and now – it’s an indelible, iconic performance that showcased his ability to create heroic, everyman characters of depth and fault, something I think had been missing from cinema of the day. Kane’s flaws go against the upright men of Western-genre cinema who never flinched in the face of danger or evil, with Cooper’s character resigned to probable death at the hands of Miller and his gang (Lee Van Cleef, Sheb Wooley and Robert Wilke, who spend a vast portion of the film waiting at the town’s nearby train station for Miller to arrive… at noon) and almost coming off as a bit of a coward. Notably for a film of this vintage, Kane’s flaws and estranged relationship with some in the town mark him as a character who just possibly might not be likeable (don’t worry, he is) and I daresay few audiences would have expected this kind of character in a typical Western.

In High Noon, we also see several templates established in films to come later; markedly, some of Fred Zinnemann’s direction here is echoed by the likes of Sergio Leone and Eastwood himself, with elements of Once Upon A Time In The West (with its train-station opening sequence) and The Good The Bad & The Ugly all appearing in embryonic form here. Zinnemann understands tension implicitly, his crafty direction and the script’s electrifying examination of justice, fear, cowardice and heroism eliciting an astonishing amount of potency even today. The manner in which Kane is all but abandoned by his fellow townsfolk, people he’s spent years protecting, is excruciating to watch and exceptional in its execution – a sequence with Cooper and former town Marshall Howe (Lon Chaney Jr in a small cameo) in which the latter exhorts the former to recognise when he should turn and run rather than face almost certain doom is crucial to the film’s sense of fatalism – and I think it’s this sense of impending self-destruction that magnifies the film’s incendiary power.

Cooper, as mentioned, is excellent here. Personifying strength and fragility and fear, he represents a deep-rooted sense of identity and righteousness, only without coming off as arrogant. Little wonder he snagged the Oscar for Best Actor, in one of the film’s four wins. Past hurts with fellow townsfolk, notably Lloyd Bridges’ Deputy Marshall Harvey Pell and the Ramirez Hotel receptionist, played by Howland Chamberlain, rear their heads up and add spice to Miller’s return as something of a deserved comeuppance or obscene revenge, while Golden Globe winner Katy Jurado, as a Mexican businesswoman with an obvious sexual history on both Kane and Miller who sells up and flees, as well as a young Grace Kelly (the film’s token damsel in distress), are solid performances indeed. Thomas Mitchell’s role as the town’s mayor is accorded high billing but never really deserves it, while Get Smart’s Chief, Harry Morgan, appears in a minor role as a cowardly member of the community.

Strangely discordant and yet wonderfully appropriately mixed into all this is the film’s indelibly memorable theme tune, classic Country-Western melody “Do Not Forsake Me, My Darling” a constant motif for the character’s gradual forsaken nature within the context of this story. The tune’s percussive underbelly assists in ratcheting up the tension of the film alongside the “ticking clock” mandate of the real-time plot, and although if you’d suggested to me externally of viewing this movie whether that was a good idea I would have strongly disagreed, the song, and indeed the entirety of Dimitri Tiomkin’s Oscar-winning score, works brilliantly. So too is Floyd Crosby’s brilliant cinematography and framing, all of which is just achingly beautiful and redolent of the Western genre’s best moments. Crosby’s use of focus, lighting and low-angles is keenly felt in keeping suspense at the forefront; despite zero explosions and only a few shortish sequences of actual violence, the film is sensationally tense and almost assaults the viewer with its aggressively strong dramatic weight. Mention should also be made of the Oscar-winning editing of Elmo Williams and Harry Gersland, who provide the real-time narrative tricks with dexterity and fluency that starts slow, and ends with a calamitous bang.

A sidebar: according to the internet, High Noon was a production rife with difficulty and personality clashes, notably between screenwriter Carl Foreman and producer Stanley Kramer and the effects of the House Un-American Activities Committee which was active at the time, where Foreman was labelled as an “uncooperative witness” and effectively blacklisted by Hollywood. His partnership with Kramer and rift with former colleagues forced him to flee to Britain. So too potential star John Wayne, whose conservative background led him to consider the film too obvious an allegory to blacklisting and decided against participating in the role of Kane. In an ironic twist, Wayne would eventually accept the Oscar for the role in place of an absent Cooper on Oscar night.

High Noon is white-hot film-making of the highest magnitude. It encapsulates so many genre elements and balances its heroism and fatalism with panache and flair. Zinnemann’s direction was met with an Oscar nomination, and the film too for Best Picture, although it would lose in both categories. Finely tuned, often electrifying and simply beautiful to look at visually, High Noon’s chipped heroes and ethically diverse supporting characters, not to mention the constant motif of “me against the world” being a touchstone for many, ensure the film’s strength and legacy remain undiminished all these years later. A classic American film, a definitive Hollywood Western, and an astutely powerful statement about many recurring evils in the world today.

Great write-up. This one definitely deserves the high marks. It’s my stack of movies that I’ve been hungry to rewatch. Hopefully soon.

This was always one of my dad’s favourite films, I must have seen it a dozen times as a young kid but not since I grew up. Def worth a look!

It’s been some years since I’ve seen this, so I’d have to watch it again to see how it deals with McCarthyism. I’m probably more interested in seeing how Leone and Eastwood borrowed from it as you mention since I saw this before Once Upon a Time in the West and years after Unforgiven. I love both of those, but failed to make the connection. Thanks for tipping me off. One thing I clearly remember is the tension it generated and that was fantastic. And of course Cooper, so good.

Oh boy, this film is tense. Surprising to note it plays out in real time too, a little like that Johnny Depp “Nick Of Time” from years back, although this one several decades before that even! I always thought that conceit was a modern one, but it’s actually a vintage film trick!