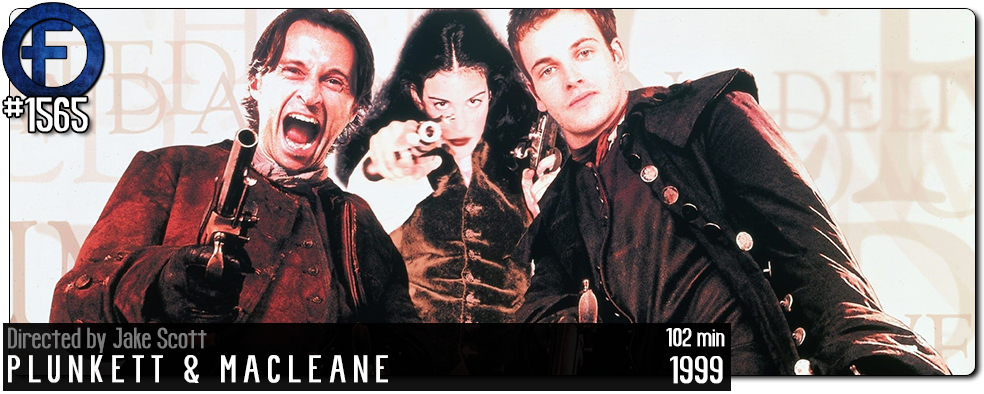

Movie Review – Plunkett & Macleane

Principal Cast : Jonny Lee Miller, Robert Carlyle, Ken Stott, Alan Cumming, Michael Gambon, Tommy Flannagan, David Walliams, Matt Lucas, Ben Miller, Stephen Walters, Alexander Armstrong, Noel Fielding, Nicholas Farrell, Iain Robertson, Claire Rushbrook, Tom Ward, Terence Rigby, Christian Camargo.

Synopsis: Two gentlemen highwaymen attempt to steal a fortune, with one trying win the heart of a young local aristocratic woman.

********

On paper, Plunkett & Macleane would be blockbuster entertainment in any cinema complex around the globe. In front of the camera, the film features a who’s-who of British talent including Trainspotting’s Robert Carlyle (who would also appear in The World Is Not Enough the very same year) and the inestimable Alan Cumming, as well as a archetypal screen villain in Ken Stott, all set against a backdrop of 16th Century England and accompanied by a thunderous score by Aussie composer Craig Armstrong (Moulin Rouge); directed by Jake Scott, the son of British directorial icon Sir Ridley Scott, and a nascent Oscar-nominee cinematographer in John Mathieson (Gladiator, The Phantom Of The Opera, Logan), you have a recipe for a movie that by rights should have delivered a showcase of top-tier entertainment. Unfortunately for distribution studio USA Films, Plunkett & Macleane was a box-office disaster in 1999, despite middling audience appreciation, and there’s little in the film’s place in history to suggest this distaste is unwarranted.

Synopsis courtesy IMDb: Will Plunkett (Robert Carlyle) and Captain James Macleane (Jonny Lee Miller), two men from different ends of the social spectrum in 18th-century England, enter a gentlemen’s agreement: They decide to rid the aristocrats of their belongings. With Plunkett’s criminal know-how and Macleane’s social connections, they team up to be soon known as “The Gentlemen Highwaymen”. But when one day these gentlemen hold up Lord Chief Justice Gibson’s (Michael Gambon) coach, Macleane instantly falls in love with his beautiful and cunning niece, Lady Rebecca Gibson (Liv Tyler). Unfortunately, Thief Taker General Chance (Ken Stott), who also is quite fond of Rebecca, is getting closer and closer to getting both: The Gentlemen Highwaymen and Rebecca, who, needless to say, don’t want to get any closer to him. But Plunkett still has a thing to sort out with Chance, and his impulsiveness gets all of them in a little trouble.

In the interests of full disclosure, at the time I first saw Plunkett & Macleane in cinemas I considered it one of the greatest films I’d seen up to that point. It hit a home run with its bawdy sense of grimy humour and alacritous storytelling, a scurvy-ridden juvenile expedition into a destitute, roguish action sensibility that smacked me right in the fun bits. It engaged me so much, I returned a number of times to bask in its glory on the big screen. Retrospectively, I’m not quite sure what I was thinking; Plunkett & Macleane retains a definite sense of playful post-modern contrast in historical provenance, and the chemistry between Trainspotting co-stars Johnny Lee Miller and Robert Carlyle as the titular characters feels effortless and fun, obnoxiously rubbing the classism and paradoxical social mores of the period together to spark at least a modicum of ribald entertainment. That doesn’t, however, make this a great – or even good – movie.

Making the most of his sub-£10m budget, Jake Scott gives this salacious screenplay all the style and sophistication he can muster, and to a certain degree he succeeds in maximising the scant fun and chuckles between a foreboding and dank setting in English history. While the story flirts dangerously with being utterly preposterous to the point of cringe, Scott’s flashy music-video direction (a genre on which he cut his teeth) imbues the film with a vibrancy strangely at contrast against Mathieson’s stunning cinematography. The film looks stunning, highlights including the amazing costume design and the detailed sets and locales in which our characters cuss and shoot their way through the story. It’s a film riven by style over substance, any element of more interesting story points (such as the embryonic attempts to form a government-funded police force) brushes aside in favour of thunderous sound design and Craig Armstrong’s dance-club soundtrack. Several of Armstrong’s cues from this film remain in heavy rotation on my iTunes playlist even today.

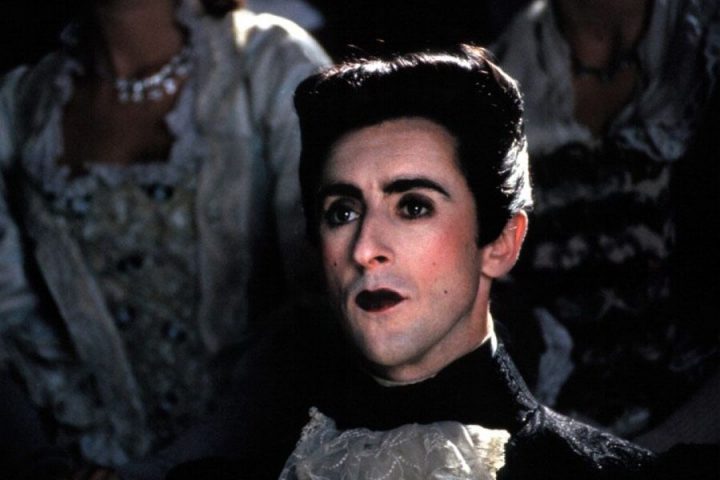

The dialogue is stuffed with innuendo and witticisms of a highly sexual nature, with Carlyle’s Plunkett offering the crassest and most direct observations on the happenings, and Miller’s fanciful Macleane trying desperately to retain a sense of sophistication despite having very little at all. The film’s stand-out character is Alan Cummings’ Lord Rochester, a “how dooo you doooo” type dilettante with a taste for the masculine and a penchant for the subversive, sees the actor achieve the rarest of cinematic feats in improving the film simply by being in it at all. His dialogue is crisply wry and juxtaposes actual class with the pretension of it.

The weakest element of the film is, sadly, Liv Tyler, miscast as Rebecca Gibson against the plethora of rockstar British thespians on show here. Her on-screen father, an obnoxiously direct Michael Gambon in full flight as Justice Gibson, easily outclasses the young actress by sheer screen presence, ably abetted by Ken Stott’s withering, Wormtongue-like performance as Thief Catcher Chance, one of my favourite all-time screen villains. Tyler isn’t strong enough an actress to deliver the cunning sexuality and underpinning stability the role demands, a requirement to be both coquettish and attractive eluding the otherwise ethereal performer. Small roles to luminaries such as perennial screen henchman Tommy Flannagan, comedian Matt Lucas (as a resident of Newgate Prison), Nicholas Farrell (as a politician keen to subvert the elder Gibson’s reign of terror) and Secrets & Lies’ Claire Rushbrook as a pox-ridden bride make for levity and brusque, oafish comedic elements that delight as often as they derail an otherwise intriguing story.

Plunkett & Macleane juggles the balance between dark humour and enthusiastic showmanship with the broad-based credibility of a drunken lumberjack. The laughs come mainly from ancillary characters and non-sequiturs, an innately drab and melancholy premise given life by Jake Scott’s potent direction, and a strange indifference to the central characters’ plight in favour of bigger and braver thrills. The performances can’t shake their modern sensibility, some of the dramatic dialogue doesn’t land as well as it ought, and the film’s about fifteen minutes too long (the middle-section does lag) which detracts somewhat from its punchy visual verbosity.

That said, even though it’s not what you’d consider a “good movie” by traditional standards, Plunkett & Macleane is a subversive, darkly enjoyable dirge of a thing that undercuts true horror with a sharp-witted facade of anarchy. Bolstered by a top-line supporting cast and sumptuous production design, the film remains a definitive cult classic and an enthusiastic effort: despite my more mature outlook finding much of this film’s aesthetic perplexingly discordant, there’s some juicy elements at work here that provide some sustenance for those looking to waste a few hours away.