Movie Review – Escape From Alcatraz

Principal Cast : Clint Eastwood, Patrick McGoohan, Fred Ward, Jack Thibeau, Larry Hankin, Frank Ronzio, Roberts Blossom, Paul Benjamin, Bruce M Fischer, Madison Arnold, Danny Glover.

Synopsis: Alcatraz is the most secure prison of its time. It is believed that no one can ever escape from it, until three daring men make a possible successful attempt at escaping from one of the most infamous prisons in the world.

********

Hard-bitten gritty American icon Clint Eastwood takes on another hard-bitten, gritty icon in the infamous San Francisco-based penitentiary known as Alcatraz, and we, the audience, come out as winners. One of few definitive prison films (alongside Papillon, The Great Escape, and more recently The Shawshank Redemption) to tackle the genre as a serious dramatic piece, Eastwood’s final film alongside director Don Siegel is a razor-wire thriller that will set your pulse pounding as a great escape is undertaken, a masterful human drama mixed with what have become shorthand cliches in today’s modern context.

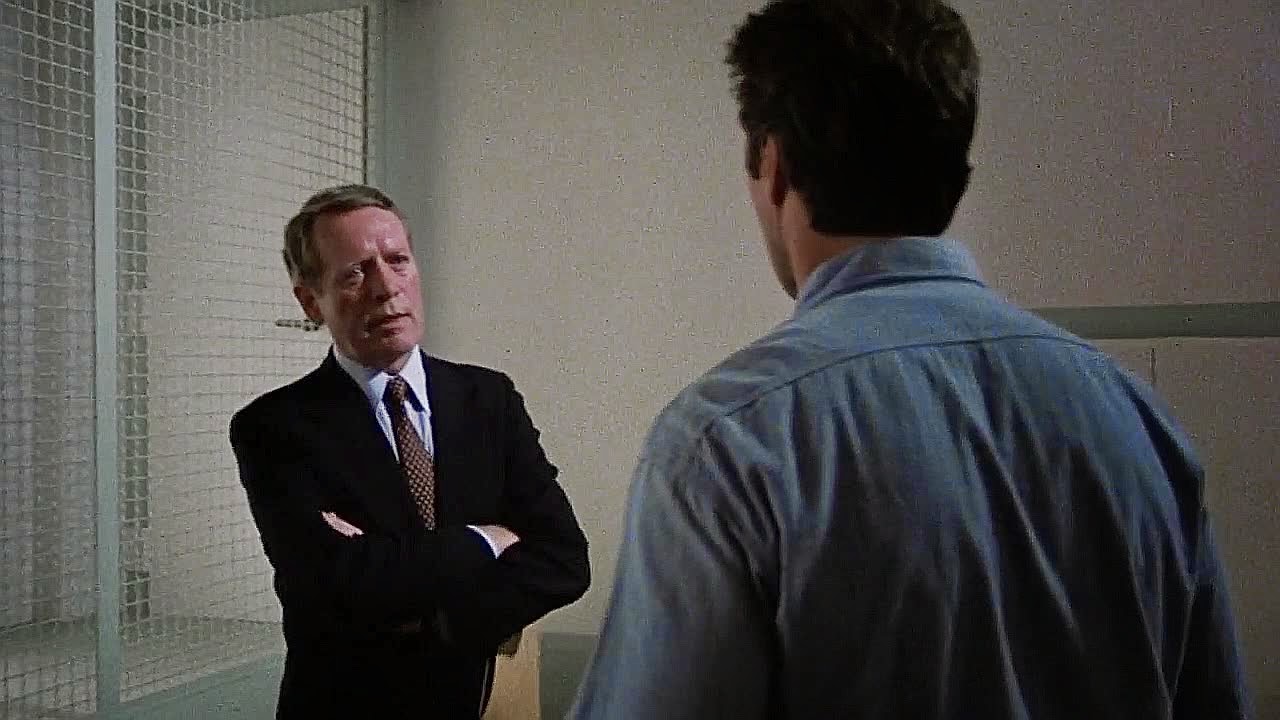

In the early 1960’s, Frank Morris (Eastwood) is sent up to the maximum security prison on Alcatraz Island, in the bay of San Francisco, after continually escaping from other facilities. He is warned by the prison’s Warden (Patrick McGoohan) that escape is impossible, and that the only way of leaving is by being dead. As he makes acquaintances with other inmates, Morris is accosted by prison rapist Wolf (Bruce M Fischer), and spends some time in solitary, where he concocts a plan of escape. He recruits new prisoner Charlie Butts (Larry Hankin) and brothers John and Clarence Anglin (Fred Ward and Jack Thibeau respectively) to help him in his escape, secretly excavating part of the crumbling prison wall and manufacturing paper mache heads to fool the guards patrolling the cellblocks, and eventually makes a break for it following the treatment of one of their fellow prisoners turns nasty.

Quietly contemplative, yet resolutely thrilling, Escape From Alcatraz is a pulse-pounding escape film like few others. Although, as my wife kept pointing out, it is alarmingly similar in many respects to The Shawshank Redemption – from the black inmate who befriends the white lead, to the elderly prisoner who eventually succumbs to the pressure and hopelessness of prison life, to the omnipresent threat of shower rape from an oversized bully, Siegel’s film has a lot of similarities to the Stephen King story; however, where they differ greatly is tone, and that counts for a lot. One has to expect that prison films by-and-large contain fairly similar themes of loss, masculine bonding and redemptive underpinnings to generate their human interest; heck, the aforementioned Great Escape, the Paul Newman classic Cool Hand Luke, and even the original The Longest Yard all contain similar archetypes and stereotypes mirrored in Siegel’s production. It’s to be expected, given the harsh and dehumanising nature of people being incarcerated in the most inhospitable establishments possible. There are remarkably few variations on the theme that extricate anything new within the genre: even modern takes on the premise contain some form of the classic tropes on display here.

What Siegel does brilliantly, however, is restrain the brutality significantly enough that he draws out the threat of violence, and/or failure, in order to sell his story. Sure, Eastwood’s Frank Morris undergoes some pretty torturous punishment within the walls of Alcatraz during his stay there, but these are flashes of despair amidst the softly-softly build up of suspense Siegel generates through his film. It’s startling to realise that Escape From Alcatraz is based on a true story (although exactly which parts are true and which are pure fabrication remain elusive even to this day) and the screenplay, by Richard Tuggle, is derived from the true-crime non-fiction 1963 book by J Campbell Bruce, who researched the story quite studiously enough to want to shop it around to multiple studios before Eastwood and Siegel grabbed hold of it. The script doesn’t build up Morris’ character so much as it interweaves his relationship with the various characters on the island prison, some of whom are immediately relatable (Roberts Blossom’s tragic Doc Dalton, who is forced to give up painting with awful results, is easily the one who pulls on the heartstrings) and some, like Paul Benjamin’s racially unambiguous English (it should be noted that the film does contain several contextually triggering uses of the N-word), who are not. It’s a slow build, a ticking clock screenplay that preys upon expectation and flips anticipation on its head at key crucial moments.

Siegel directs the film with precise ferocity. The film’s escapist narrative inherently builds tension but there’s a restraint and luxury of time within Siegel’s editing and camerawork that really ratchets up the electricity. Eastwood, as silent and stoic and brooding as he always is, commands the screen in every inch, alongside the rag-tag ensemble of supporting players (blink quick for a minor cameo from future Lethal Weapon star Danny Glover) who all deliver convincing and evocative performances on characters that often fall foul of cliche. Patrick McGoohan’s eponymous Warden, the antithesis of Eastwood’s inbuilt charm and anti-hero machismo (remember, Morris is in prison, and isn’t somebody we ought to be rooting for, although by the end of the film we’re wholeheartedly behind his escape attempt); the Warden provides the role of gatekeeper and forms the prototypical replication of Ananke, the ancient Greek goddess of bonds in mythological terms, against whom the more noble Morris rails. Siegel’s unflinching gaze solidifies his status as one of the 70’s great directors – he made five other films with Eastwood, including Dirty Harry, Coogan’s Bluff and Two Mules For Sister Sara – and it’s through this carefully constructed sense of claustrophobia that he engenders so much potency.

Adding to the credible truthfulness of the film is Jerry Fielding’s quiet, nearly invisible score, which surfaces ever so infrequently to inhabit such subtlety as to be almost impossible to remember. If a score could be so deeply embedded within the construct of a film that you don’t actually notice it when it arrives, Fielding’s work here would be just that. Escape From Alcatraz has a lot of quiet moments, a lot of lengthy montages and “time passing” segues, but it also has a lot of close-quarter terror as our quartet of escapees nearly, sometimes, almost get caught. It’s these moments that make you realise how insidiously nuanced Fielding’s score is, almost background to the on-screen action and yet so attuned to the frisson of heartbeating humanity you can’t imagine one without the other. Bruce Surtees’ cinematography, by contrast, is like a blistered finger; raw, murky focus and gritty photography make for a very documentary-like feel to the movie, perhaps more a holdover from classic 1970’s techniques and technology than any specific creative choice, and yet given Escape From Alcatraz surfaced the same year Alien came along I expected perhaps a modicum more proficiency behind the camera.

Escape From Alcatraz is a prison-break movie that works superbly well: from the dynamite scripting, the on-point acting (only Eastwood could pull of this kind of square-jawed, sullen role so well) and terrific direction from Don Siegel, every facet of the film combines to produce a sweaty, hopeful masterpiece. Although time hasn’t been kind to the genre in which Alcatraz squarely sits, retroactively condemning it for producing such archetypal tropes is hitting well below the belt. Taking it as a product of its time, the film’s dirt-stained griminess enthuses the audience with an immediacy of tension, of inhumanity against a backdrop of concrete, hopelessness and brotherhood. It’s a terrific dramatic thriller, and a remarkably capable genre flick that holds up to this day.