Movie Review – Triple Trouble (1918)

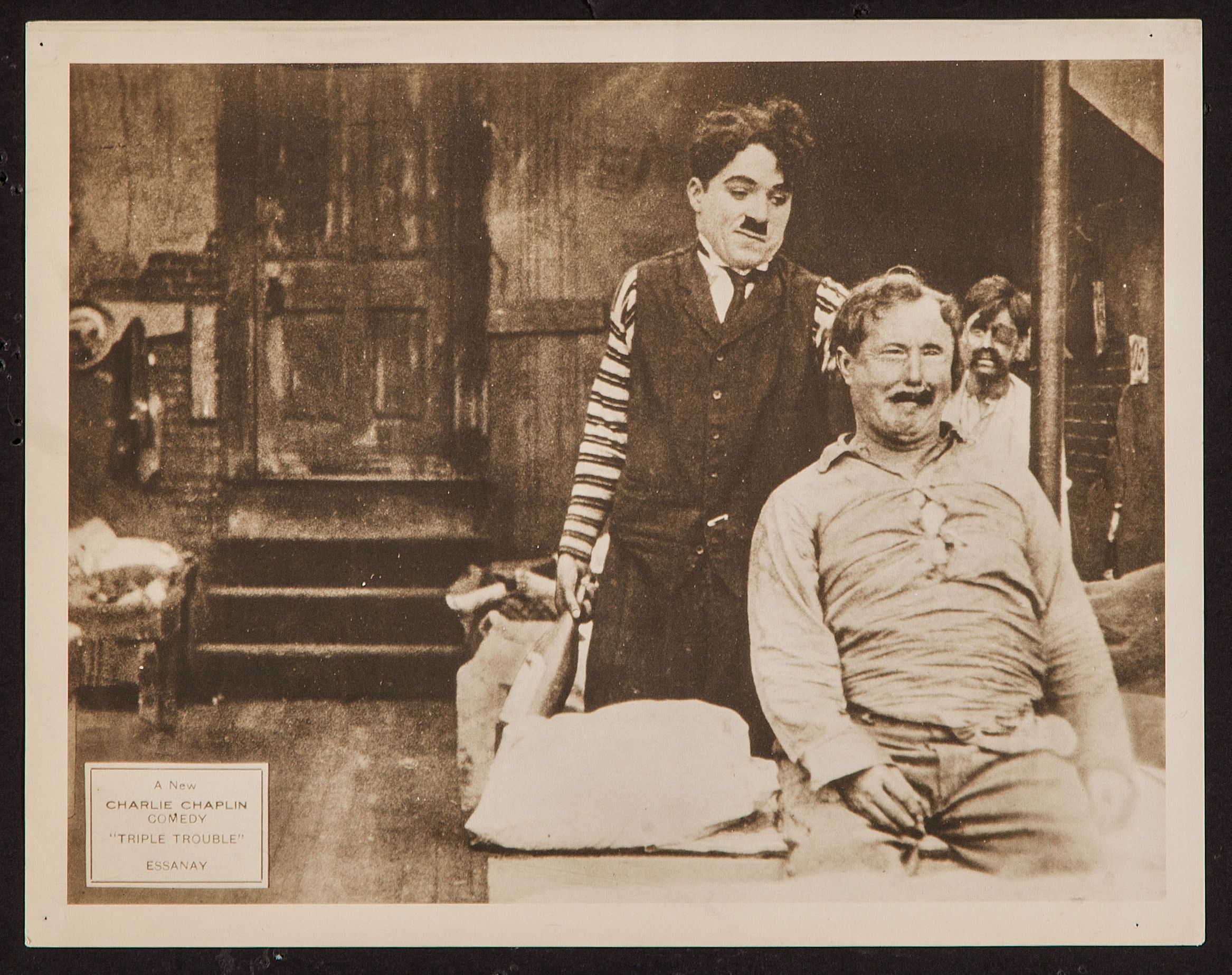

Principal Cast : Charlie Chaplin, Edna Purviance, Leo White, Billy Armstrong, James T Kelley, Bud Jamison, Wesley Ruggles, Albert Austin, ‘Snub’ Pollard.

Synopsis: As Colonel Nutt is experimenting with explosives, a new janitor is joining his household. The inept janitor proceeds to make life difficult for the rest of staff. Meanwhile, a foreign agent arrives at the house in hopes of getting Col. Nutt’s latest invention. The inventor throws him out, so the agent then employs a thug to get the formula. When police head to the Nutt home to start an investigation, a complicated fracas ensues.

********

Triple Trouble has a contentious history for Chaplin fans. Cobbled together from a variety of sources, loosely slapped together by producing studio Essanay at the end of the director’s tenure with them, and advertised without Chaplin’s approval, Triple Trouble represents the pinnacle of corporate malfeasance during the silent era. With Chaplin leaving the studio to go to Mutual, Essanay held back releasing some of Chaplin’s final reels, attempting to capitalise on them later with a release of “new” material that, whilst not authorised by the director, could bring them in some easy money even though he was no longer working for them. Parts of Triple Trouble come from outtakes of Chaplin’s 1916 film Police, other parts from an unfinished film entitled Life, and a reparsing of the ending of Work (1915), Triple Trouble is a literal cinematic Frankenstein’s Monster running around 20 minutes long and failing utterly to remain either coherent or accessible as a narrative short film.

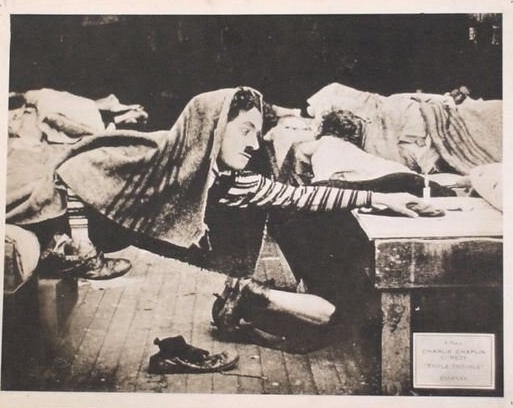

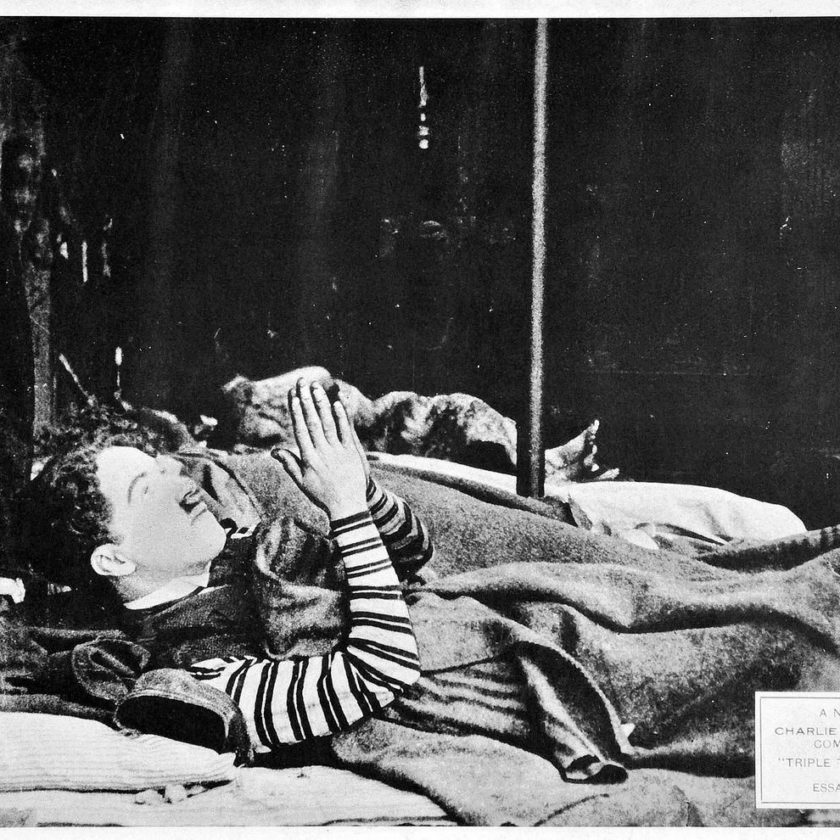

Charlie (Chaplin) takes a job as a janitor in the home of Colonel A Nutt, who is developing a wireless explosive that proves to be impossibly enticing for a variety of greedy thieves and criminals. After meeting Nutt’s daughter (Edna Purviance), for some reason the film takes an extended sojourn into a nearby flophouse, where Charlie battles a variety of sleep-depriving vagrants and characters of ill repute, before somehow evading capture by a gaggle of impossibly insane policemen.

Nothing about Triple Trouble makes sense, when you stand back an observe the overall released film. In it’s disparate parts, there are elements that are quite amusing – the five coppers cartooning it through the Nutt house (gettit, nut house?) proved to elicit a minor guffaw, an echo of the Keystone Kopps perhaps… – but there are long stretches of this brief comedic short that simply don’t work at all. The entire sequence inside the flophouse, which takes up a significant portion of the film’s middle section, is mainly unfunny, as if the comedy prolapsed from the segments that came before and never recovered. Chaplin is his usual gregarious self, mugging for the camera and offering his typically fidgety mannerisms to mild effect, but without a competently told story the film’s scattershot narrative brings it totally undone. Edna Purviance appears for about a minute of screen time before disappearing completely, the subplot involving Colonel Nutt’s explosives expires far too early on, and the bumbling editorial work on what few “action” sequences there are within mitigate a lot of the potential Triple Trouble may have had.

The film’s direction is unofficially credited to both Chaplin and co-star Leo White, the latter of whom was reputedly strongarmed into shooting several bridging scenes and reshooting others entirely; that the film was released at all speaks not only of the desperation of Essanay to recoup any earnings they could from their former star, but the voracity with which Chaplin’s output was swallowed up by audiences of the day. Demand for new Chaplin shorts far outstripped the director’s ability to deliver, and so any material directed by the famed comic would have generated significant income for whoever held the rights. Triple Trouble wasn’t a failure commercially (although modern reviewers have largely decried it as one of Chaplin’s “worst” films, despite him having no control over its eventual form and release) but it represents the nadir of studio-mandated tinkering, especially when a quick buck could be made off somebody else’s hard work.

Trying to look for a positive: Triple Trouble’s minor humour is derived from the brief moments of slapstick farce Chaplin was obviously dabbling with elsewhere. The aforementioned half-dozen policemen who storm through Colonel Nutt’s house looking for criminals (after being seen a scene previously playing craps in an empty lot for some unknown reason) are played purely for laughs, a veritable die-cast comedic cliche of sped-up motion and cavalier personal space invaders, whilst a triptych room sequence involving a wet facecloth is archetypal silent comedy gold. But an ongoing flophouse sequence, a protracted example of things going wrong for Chaplin as director, grinds the formerly freewheeling film to an absolute stop – exactly why the sequence is included within the overall context of the film isn’t clear, and it’s obvious the footage was brought in from another project Chaplin had been working on and shoehorned into place by meddling studio suits – and makes no sense whatsoever.

Sadly, there’s little to enthuse about Triple Trouble when it’s so obviously designed to capitalise on Chaplin’s popularity instead of displaying any artistic or creative endeavour. This isn’t Chaplin’s fault, and his disavowment of the finished film is borne out in just how belaboured the gluing together of the film’s seams are, but as a curiosity alone I guess it’s worth one look. The lack of quality Purviance, the ludicrous editing and the baffling differences in tone between one segment and the next, make Triple Trouble a genuine Chaplin Chore to get through. Little wonder it’s so poorly regarded. As a short film, it’s about twenty minutes too long.