Movie Review – Hamlet (1996)

Principal Cast : Kenneth Branagh, Derek Jacobi, Julie Christie, Richard Briers, Kate Winslet, Nicholas Farrell, Michael Maloney, Rufus Sewell, Robin Williams, Gerard Depardieu, Timothy Spall, Reece Dinsdale, Jack Lemmon, Ian McElhinney, Far Fearon, Brian Blessed, Billy Crystal, Simon Russell Beale, Don Warrington, Ravil Isyanov, Charlton Heston, Rosemary Harris, Richard Attenborough, John Gielgud, Judi Dench, John Mills, Ken Dodd.

Synopsis: Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, returns home to find his father murdered and his mother remarrying the murderer, his uncle. Meanwhile, war is brewing.

********

Few films hold a special place in my heart as Kenneth Branagh’s 1996 masterpiece, Hamlet. It’s a legendary thing: one of the last films shot entirely on 70mm film for almost two decades (until Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master in 2012), a bladder-bursting running time of a tick over four hours, and an all-star transcontinental cast of acting royalty, all led by Branagh himself in the title role, Hamlet was one of the first films I would own as a “special edition” VHS version back in the day, the full unabridged text brought to life in vivid widescreen technicolor. It’s a breathtaking achievement indeed, not only for the fact that it remains a towering cinematic treat but a great film regardless of its length. The film was shown in an abridged 2-hour version in some markets, but the full four hour epic is what you really need to see to appreciate the full scope of Branagh’s vision.

Hamlet (Branagh) is the Prince of Denmark; his father, the late King (Brian Blessed) has been murdered via poison, and his mother, Gertrude (Julie Christie) has married the King’s brother, Claudius (Derek Jacobi) far too quickly for Hamlet’s liking, taking the throne. Beset by visions of his later father haunting him, Hamlet rejects the advances of the adoring Ophelia (pre-Titanic Kate Winslet) and the advice of his numerous aides, notably Horatio (Nicholas Farrell), whilst Claudius’ belligerent attitude towards Polonius (Richard Briers), father of Ophelia and Laertes (Michael Maloney) sets his monarchy on course for almost certain destruction.

There are remarkably few films that can be described as “prestige”, and even fewer than can actually claim it with any legitimacy. Branagh’s version of the classic Shakespeare play, the one we all hated reading in high-school, is a masterwork of visual design and performance, a mind-blowing cast of Hollywood luminaries in even the smallest of roles, and is a riveting, nay hypnotic luxury experience unlike any other. I haven’t seen every adaption of Shakespeare’s work ever made but of those I have, this stands head and shoulders above them all. It’s not just the production value and the plethora of quality thespians on the screen, but the sheer brilliance of Branagh’s direction of dialogue and plotting that otherwise would be as confusing and nonsensical as all get out. Don’t be put off by Hamlet’s inordinate length (and it is extraordinarily long!), the sumptuous design and evocative imagery used to bring this literary masterpiece to life.

Anyone who’s ever studied Shakespeare at school or in their adult life will be familiar with the story, a story of murder, madness and war. Branagh leads the cast as Hamlet himself, the mad Prince of Denmark driven to insanity by the death of his father and the incestuous marriage of his mother to his uncle. As a performance, Branagh’s is a commanding, palpably tangible essay of madness and he handles the complexity of the character’s motives and emotional arc with specificity and grace. His wild-eyed mania, coupled with his command of Shakespeare’s poetic text to make it feel believable is one of the film’s chief selling points to Shakespeare newbies: while it takes a bit to get your head around the flowery language – in which the simplest idea is given three minutes of forsooths and whereforeartthous – there’s a sense and meaning to it that honestly used to lose me in other films like this.

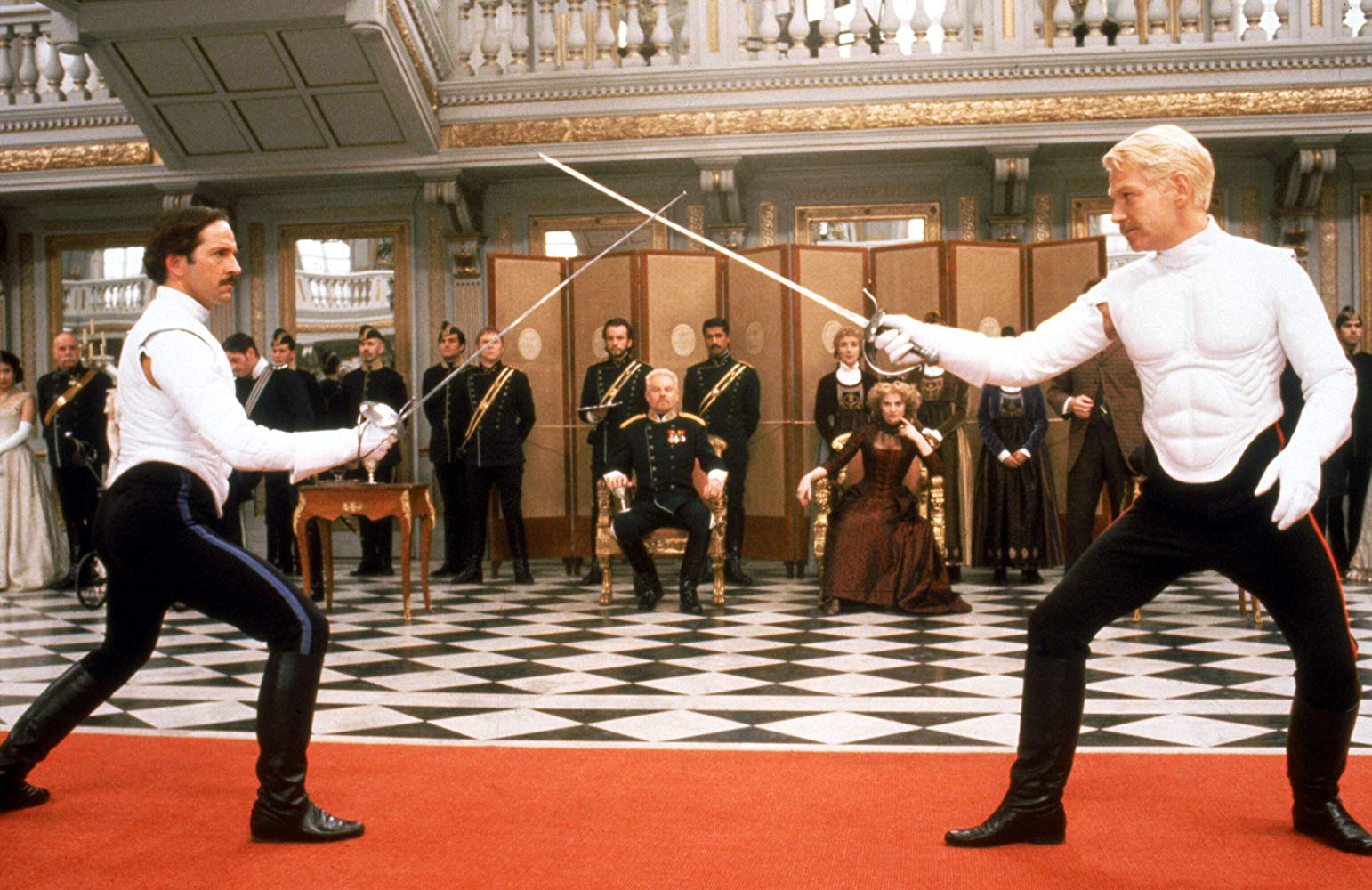

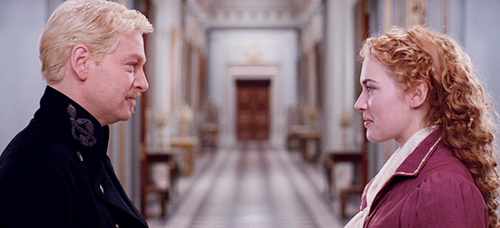

Alongside Branagh, the likes of Derek Jacobi and Julie Christie, together with a young Kate Winslet and terrific Michael Farrell, all deliver superb turns in their respective roles of Hamlet’s extended family and associates. Ophelia’s transition from beautiful young ingenue into straightjacketed banshee is brilliantly done by Winslet, in a heartbreaking turn, and Jacobi has never been better than he is as Cornelius. Julie Christie is radiant as Gertrude, whilst an underrated Richard Briers, as the ill-fated Polonius, holds the early part of the film together like glue. The film also features Rufus Sewell (Dark City) as the Norwegian Prince Faltinbrass, whom Shakespeare only mentioned and referenced occasionally, now fleshed out in a non-speaking extended supporting role. A lot of Hamlet’s world-building of based upon speculative licence from Branagh, utilising classically trained British talent to flesh out the backstory – Judy Dench, John Mills, and Sir John Gielgud appear as historical figures of Hamlet’s backstory – that adds texture to the luscious exposition. They aren’t the only ones: an orgy of screen talent permeates the screen, from the likes of Charlton Heston and Rosemary Harris as leaders of an acting troupe who arrive to entertain the new King, Jack Lemmon as a palace guard, Timothy Spall as Guildenstern, Billy Crystal as a gravedigger for the “alas poor Yorick, I knew him well” scene, and even a vastly out-of-place Robin Williams as Osric, a courtier who oversees the climactic fencing duel between Laertes and Hamlet.

But it’s the directorial flourish behind the camera that is of particular interest to me. Branagh has a masterful command of the cinematic language here, delivering a luxurious widescreen frame filled with terrific big-screen framing and wonderfully technicolor photography. Alex Thompson’s cinematography using the 65mm film stock allows for a detailed, crisply vibrant image that maximises every square inch of the 2.35 aspect ratio, the central set-piece being the cavernous Danish throne room. Branagh uses a lot of mirrors throughout the throne room’s decals, allowing a surprisingly effective reflectivity within the space that subtly warps the perception of the leading players. The lavish set design and Thompson’s lighting techniques are dynamite, a brilliant tapestry of costume and set design working in concert to deliver a resounding visual triumph that trumps any epic film beside it. From the nightmarish dankness of the Danish forests, the saturated blue of Ghost King arriving periodically throughout, to the primary-coloured costuming of the various courtiers, and even Hamlet’s dark brooding black suit, Alexandra Byrne’s Oscar-nominated costume design remains one of the film’s greatest achievements.

I don’t know how easy it will be to recommend a four hour Shakespeare film to all but the hardest of hardcore Shakespeare fanboys. It’s a tough sell to casual viewers anyway, especially one that’s “unabridged” in every sense of the word: this isn’t a two hour trimmed-down take on Hamlet, this is the full thing. But Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet is a masterpiece, a truly remarkable cinematic (or home theatre) experience that needs to be seen on the largest possible screen. Very few films come along that elevate their genre in such a way, but Hamlet does just that. A monumental film in both time and experience, Hamlet is a gargantuan work of art that should be far more appreciated in the annals of Shakespearean cinema than it is; worthy of Olivier, maybe Branagh achieves something similar with far more, but the film world is the richer for it.