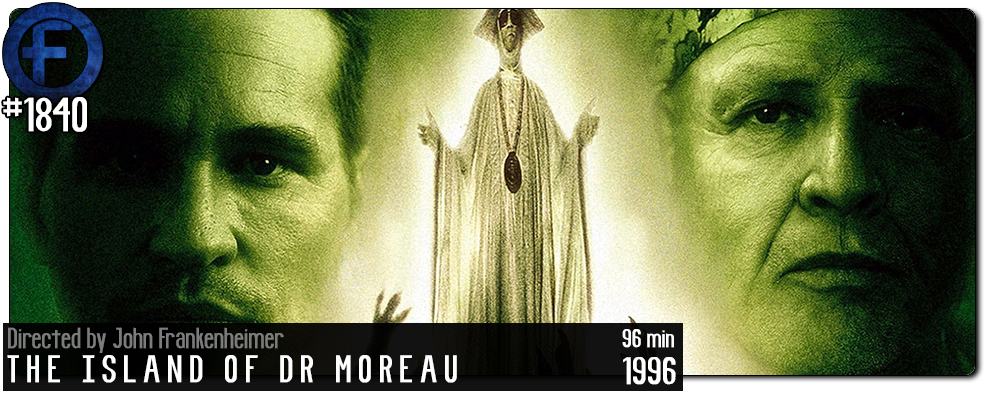

Movie Review – Island of Dr Moreau, The (1996)

Principal Cast : David Thewlis, Val Kilmer, Marlon Brando, Fairuza Balk, Daniel Rigney, Temuera Morrison, Nelson de la Rosa, Peter Elliot, Mark Dacascos, Ron Perlman, Marco Hofschneider, Miguel Lopez, William Hootkins.

Synopsis: After being rescued and brought to an island, a man discovers that its inhabitants are experimental animals being turned into strange-looking humans, all of it the work of a visionary doctor.

********

Mired in production problems, not the least was the suicide of star Marlon Brando’s daughter, and Val Kilmer’s enormous ego eventually forcing out the film’s original director, the 1996 adaptation of HG Wells’ The Island Of Dr Moreau is a film experience of puzzling proportions and eccentric missed opportunity. It’s also an absolute shambles, perhaps the second film in which Brando was associated to have so much behind-the-scenes issues (the first being Apocalypse Now, regarded as the granddaddy of “production woes” legend); it’s a film I initially saw in cinemas and came away thinking I’d just seen some misunderstood nightmare, and revisited on DVD back in the day with similar thoughts. To push this legendary film back under the microscope with its recent re-release in HD is just too temping a gamble for my far more discerning tastes, so I gave it a whirl to see if the fuss at the time was justified.

Boy, was it.

Plane-crash survivor Edward Douglas (David Thewlis, then cresting a wave of big projects off the back of Divorcing Jack and DragonHeart) arrives by chance on a mysterious tropical island located somewhere near Java, thanks to his rescue by one-time neurosurgeon Dr Montgomery (Val Kilmer), where he is introduced to the equally mysterious and far more eccentric Doctor Moreau (Marlon Brando), who has spend the past twenty-odd years performing genetic experiments on animals, creating a society of deformed hybrid “freaks” who exist in squalor and unequal footing with the malignant scientist. Douglas meets Moreau’s “daughter”, Aissa (Fairuza Balk), as well as a vagary of denizens of the island including Azazello (Temeura Morrison), a dog-like creature who serves at Moreau’s pleasure, a violent hyena-pig deformity (Daniel Rigney) who lusts after power and escape from Moreau’s brutal regime, and Lo-Mai (Mark Dacascos), a humanoid leopard creature who has broken several of the island’s many “rules” and is therefore due to be punished. As Douglas attempts to escape the nightmarish island and its inhabitants, he is drawn into the class struggle of the creatures and those who control them, in a weird meshing of Lord Of The Flies meets The Wolfman.

The problems associated with The Island Of Dr Moreau’s production have become the stuff of Hollywood legend – the film was labelled by many as cursed, an abortion project perhaps best left on the studio shelf: well before they produced Peter Jackson’s Lord Of The Rings, New Line Cinema (and founder Robert Shaye) plumbed the depths of how terribly a movie’s production can go wrong to produce a film so egregiously awful it almost transcends the appellation. The problems began early on in pre-production, with several big-name actors cast in the leading roles (including Bruce Willis), and South African director Richard Stanley (Hardware, Color Out Of Space)attached to helm. For Stanley, this was an absolute passion project, and he had pitched the original idea from HG Wells’ novel to New Line, and planned to film in a Far North Queensland location. Stanley had also snagged Hollywood titan Marlon Brando to star, which gave him significant clout against ongoing studio interference.

As filming began, lead actor Val Kilmer’s behaviour started to become a problem, ostensibly due to his impending relationship breakup with wife, actress Joanne Whalley, and his treatment of both Stanley and his fellow castmembers took quite the toll. The original actor cast to play Edward Douglas, Rob Morrow, dropped out on only the second day of shooting, and bad weather in the region had halted filming for a protracted period. New Line abruptly fired Stanley and replaced him with a far more aggressive director in John Frankenheimer, who would not suffer the likes of Kilmer gladly. This was all on top of Marlon Brando suffering a personal tragedy prior to filming; his daughter Cheyenne took her own life, resulting in the actor almost completely withdrawing in grief.

The film also suffered from a considerably schizophrenic script: following the director-switch, Richard Stanley’s original script was plundered and altered almost daily by incoming screenwriter Ron Hutchinson and various members of the cast (particularly Kilmer and Brando, neither of whom were on speaking terms for most of their time on the project, to the point they almost derailed the film entirely) while Frankenheimer attempted to cobble together a workable story and performances from his often inhospitably costumed cast. A lot of the actors involved had to wear enormously hot costumes (in the tropical North Queensland weather, this would have been intolerable) and highly complex prosthesis on their faces, and tension mounted on-set each day as Frankenheimer worked to salvage what he could from this potentially ruinous experience.

Much like many of the deformed, hideous creatures depicted in The Island Of Dr Moreau, the film itself is a tortured, fractured cinematic abomination. There’s a galling sense of what might have been had Stanley not been replaced, or had Val Kilmer swallowed his pride and actually wanted to be involved, or if a hundred other things hadn’t gone wrong here. That the film is as coherent as it ends up being is a minor miracle, for the characters, overarching story points and central premise remain quite strong. It’s a film in search of itself: sodden studio blockbusterism attempting to exacerbate more intellectual themes of identity, power and social constructs runs this film right off the rails, aided by a bizarre Brando performance and Kilmer’s nonchalant arrogance seeping through every frame. The film favours excess when it could have shown restraint, examining deeper human qualities without the garish, half-baked visual effects extravaganza we are subjected to. It plays as a weird, off-centre horror film, with copious gore, animalism and primitive groupthink terror, but Frankenheimer can’t balance the salaciousness of the visuals with anything close to the literary brilliance of Wells’ original text.

To be honest, the film’s MVP is actor David Thewlis, who makes quite a good showing as Edward Douglas despite lower billing and the film’s complete inability to turn him into somebody we invest in. His introduction is fraught with problems that are never resolved, his character arc is insipid, and the poor guy spends a large portion of the film with the camera far too close to his face, but he’s arguably the best thing about this whole sorry affair and that’s for a film with Fairuza Balk in it. Ahh, Balk. Poor thing, cast to play a weird sexy cat-hybrid creature and going for broke against nonsensical plot points, undercooked secondary characters (mostly of the non-human variety) and looking entirely out of her depth, Balk is amenable to the eye but ultimately underutilised in many ways here. Putting an actor of the calibre of Temuera Morrison, who had snagged critical praise for his turn in Once Were Warriors, under such heavy makeup and expecting to get something decent out of him was always heading for failure, while Daniel Rigney’s turn as the “Hyena-Swine”, the film’s central antagonist aside from Kilmer, is both laughably stupid and credibly memorable for just how evil he is. Mark Dacascos is unrecognisable as a leopard creature, and Ron Perlman’s blind goat-creature soothsayer character suits the hulking actor down to the ground.

I’m loathe to mention Val Kilmer, if only because his sour, dullard performance here reeks of spectacular overachievement. At one point he don’s Moreau’s astoundingly impractical costume and white paint and mimic’s Brando’s delivery and mannerisms – you have to wonder if Brando signed off on that – and it’s cringeworthy for nothing but sheer showboating. I generally find Kilmer to be an actor who seems to actively hate acting, unaware maybe that he gives off the vibe of somebody who’d rather be elsewhere entirely, and it’s never been so acutely present on screen than it is in this movie. Montgomery is arguably the least interesting character in the film and Kilmer tries to overplay his role with a generally terrible performance.

The film blends the practical costumes and live-action film techniques with a really low-grade level of then nascent CGI, often with laughable results. When some of the animal hybrid characters have to move in distinguishably non-human ways, the CG takes over and it’s ropey as hell – of all things wrong in the film, the computer graphics haven’t aged well in the slightest. But the practical effects, from the costumes and stunts to the enormous sets within the Queensland rainforest, are superb, particularly those around Dacascos’ Lo-Mai and Rigney’s Hyena-Swine, which generate a weird primal fear inside the viewer as they utterly and completely inhabit their roles. The costuming on Brando is laughable, at one point wearing what looks like an enormous thimble on his head whilst pontificating around a piano with a disfigured dwarf by his side (Nelson de la Rosa), but you’d give it a pass because, well, it’s Marlon Brando.

Most of HG Wells’ writing is cast adrift in this adaptation, a stunning cinematic ablution trying to dissect the human condition – ie, what makes us human? – and energise an audience after cheap, schlock thrills. In terms of the latter, The Island Of Dr Moreau succeeds (about the only thing it gets right), but when it comes to a cogent, understandable premise and/or characters to care about, the film owes more to Lord Of The Flies, Waterworld, and Mad Max than it does to HG Wells. Awful writing and some terrible performances perplex and overwhelm alongside some admittedly gorgeous photography and genuinely gratifying creature designs and costumes, but this whole movie is a shambolic clusterfuck of actor ego and studio interference, and should be avoided where possible. If you must, sit back and enjoy the green-hued depravity of it all, and consider what might have been had Richard Stanley remained in charge (a feature documentary about this movie’s production is available if you look carefully); everyone else can skip it.

I’ve heard lots of crazy stories about what went on with this, too, but I’ve never watched it. I have thought about it, and told myself that I would someday. However, when I got to the phrase “shambolic clusterfuck,” I knew I had to make this movie a priority. I’m not sure your intent was to steer me toward the film rather than away from it, but dammit, that’s what happened.

You shall not be disappointed. It’s rare you can see a film literally fall apart as it goes along but this trip to the island will not sell you short, my friend.