Movie Review – Island Of Lost Souls (1932)

Principal Cast : Charles Laughton, Richard ArLen, Leila Hyams, Bela Lugosi, Kathleen Burke, Arthur Hohl, Stanley Fields, Paul Hurst, Hans Steinke, Tetsu Komai, George Irving.

Synopsis: A mad doctor conducts ghastly genetic experiments on a remote island in the South Seas, much to the fear and disgust of the shipwrecked sailor who finds himself trapped there.

********

The first English-language film version of HG Wells’ “The Island of Dr Moreau”, Erle Kenton’s 1932 Island of Lost Souls is an early horror film from Paramount that found itself caught up in controversy upon release. Notable for being censored for allusions to religious heresy, Island of Lost Souls is a remarkably effective adaption of the Wells’ story, with strong characterisations – particularly from star Charles Laughton in the Moreau role – and startling makeup creature effects, as evocative and mysterious a version as there ever has been.

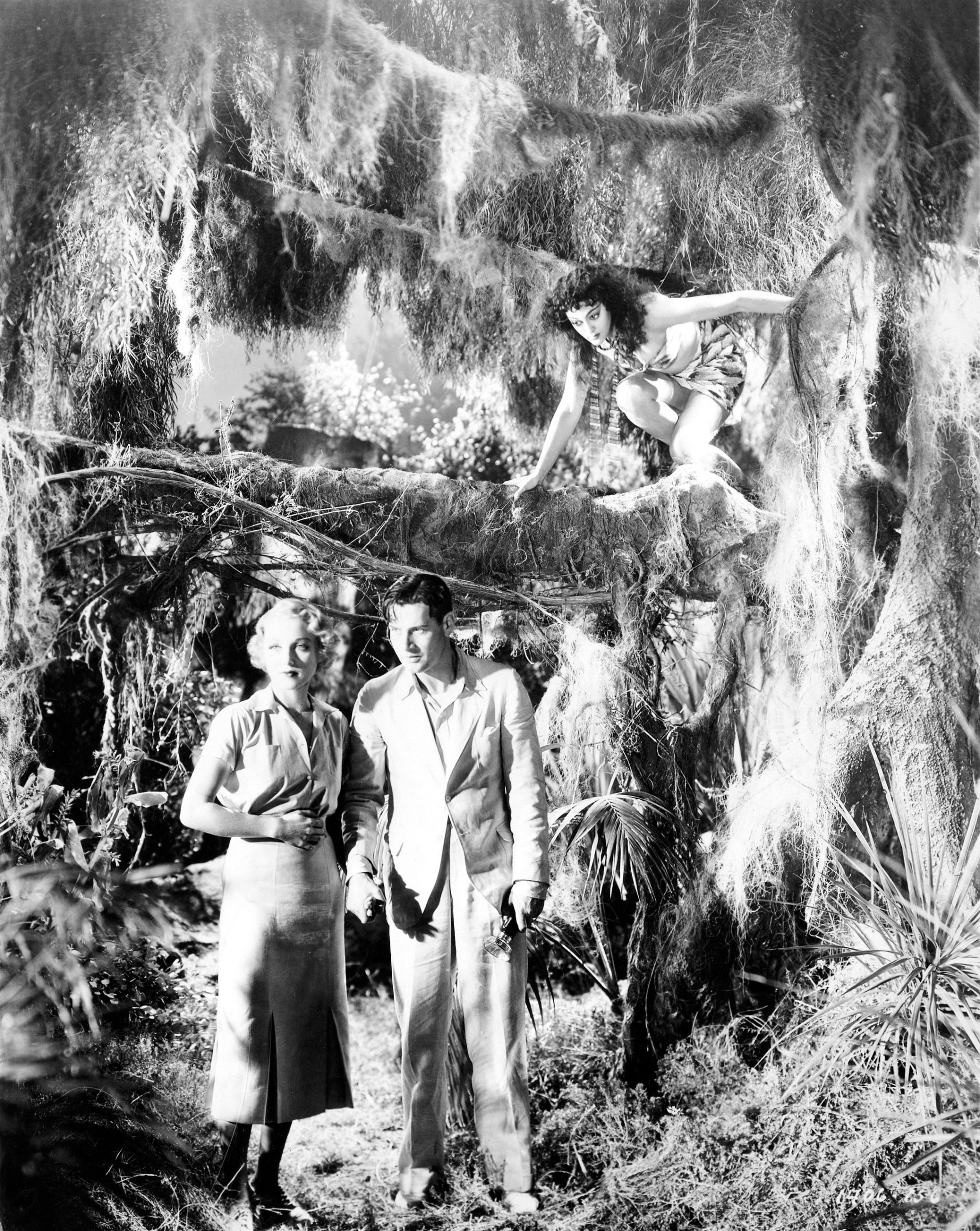

After being rescued from a shipwreck in the South Seas, young Edward Parker (Richard Arlen) is dropped off at a nearby island by the alcoholic captain (Stanley Fields) along with a mysterious Mr Montgomery (Arthur Hohl). They arrive on the island to find it populated by bizarre humanoid hybrid creatures, ostensibly scientific experiments conducted by the prickly expatriate Doctor Moreau (Laughton), who has been ostracised from society for what is deemed a taboo subject. He has been blending human and animal DNA to create a subservient underrace, one of which, the Sayer of the Law (Bela Lugosi) appears the leader. One of his creations, Lota (Kathleen Burke, credited as “the Panther Woman”), finds herself attracted to Parker, despite he having a fiancée (Leila Hyams) who is searching the Pacific for him with American consul Captain Donahue (Paul Hurst).

In the early 1930’s, horror films were all the rage in Hollywood – successful productions of Dracula, Dr Jekyll & Mr Hyde, Freaks, Frankenstein and The Mummy led studios to fast-track any horror property they could buy the rights to, for they were easy and relatively cheap to make. HG Wells’ “Island Of Dr Moreau” was a hitherto untapped property for English-speaking audiences, particularly the American market unfamiliar with both the silent French and German versions of previous years. Paramount, hoping to springboard off the back of Universal’s success, tapped prolific silent-and-sound director Erle C Kenton (who would eventually work for Universal on their horror franchise sequels The Ghost of Frankenstein and House of Dracula) to make Wells’ novel into a big-screen horror outing, with state-of-the-art creature effects and a purely gothic aesthetic.

Wells’ text was distilled down to a screenplay by the writing team of Waldemar Young (1926’s The Blackbird, and the the 1929 Lon Chaney starrer Where East is East, among others) and prolific young author Philip Wylie, who lasered in on the subtextual religious themes and evocative Darwinism layering to craft an effective, truly chilling cinematic gem. The screenplay’s dialogue ran afoul of the relatively liberal censors of the day, who objected to allusions of Moreau believing him to be a parallel or analogous version of God, as well as a rather horrific sequence in which Moreau appears to be vivisecting one of his creations. Consequently, the film suffered a number of cuts to make it more appealing to audiences across America, and it wasn’t until relatively recently the film was restored to its original form. That a pre-code film would find itself embroiled in such controversy was relatively rare (from what I understand) but even now, with modern eyes subjecting it to critique, Island of Lost Souls is quite the potent mix of drama and horror.

British stage actor Charles Laughton had made the transition to a Hollywood screen career soon after crossing the Atlantic, where he debuted in a Boris Karloff project The Old Dark House (1932), the first of six films he would appear in in that year alone, alongside Island Of Lost Souls. It was quite the opening salvo to a much lauded career, and as Moreau Laughton is quite magnetic. Unlike, say, John Frankenheimer’s abortive 90’s version, this film’s Moreau is central to the story rather than tangential, a pivotal axis around which everyone swirls. Richard Arlen’s Edward Parker is the bewildered and increasingly terrified unwitting voyeur to Moreau’s inhuman experiments, and he portrays our disgust and horror at what transpires quiet well, with a square-jawed heroism when things take an ugly turn (as they always do). The performance of Kathleen Burke as Lota, the half-panther, half-human hybrid is also rather good, mixing a sense of muse and virginal innocence with her doe-eyed sweetness. Leila Hyams maximises her comparatively limited screen time in the latter half of the film to work some delicacy into her desperate fiancée character, searching for Parker. And poor Bela Lugosi, buried beneath makeup, is utterly unrecognisable to the point it could quite literally be anyone under there, as the Sayer of The Law; what a waste of his talent.

While everyone is giving great performances in front of the camera, Erle Kenton is doing an equally terrific performance behind it. Island of Lost Souls is eerie, creepy, mysterious and pulsating with malevolence, with several genuinely skin-prickly sequences that work superbly despite the near century of time between then and now. Kenton really evokes the Universal style with this, his command of lighting, editing and design – particularly in the stellar 1930’s makeup effects, which are really quite remarkable – is second to none. In truth I wasn’t expecting Island of Lost Souls to work as well as it did as a horror, mainly because it wasn’t on my radar as a “classic” horror in the commercial sense I’ve come to know, but the film legitimately surprised me, if not occasionally creeped me out. Kenton uses rear projection brilliantly (a cave sequence utilising it early in the movie looks seamless) and his use of framing for crucial genre frights is exemplary. He cuts exposition and conversational dialogue so fluidly it never seems jarring, and his ability to build up tension is maximised even with a film clocking in at just over an hour. Even if the dialogue and characters weren’t so well procured, Island of Lost Souls would still be a markedly great movie purely as a visual exercise.

Island of Lost Souls isn’t a film you immediately think of when you recount old 30’s horror. It probably isn’t even in the top ten choices you might make. That, sadly, would do the film a disservice, for it is quite the effective genre entry. Led by Laughton’s creepy performance, enabled by some brilliant makeup effects and paying off with dynamite horror editing and truly kinetic cinematography (praise be to DP Karl Strauss, whose work on Murnau’s Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans remains the definitive silent film work, ever), Island of Lost Souls is a great entry into the genre and thoroughly deserves re-examination.