Movie Review – Rebecca (2020)

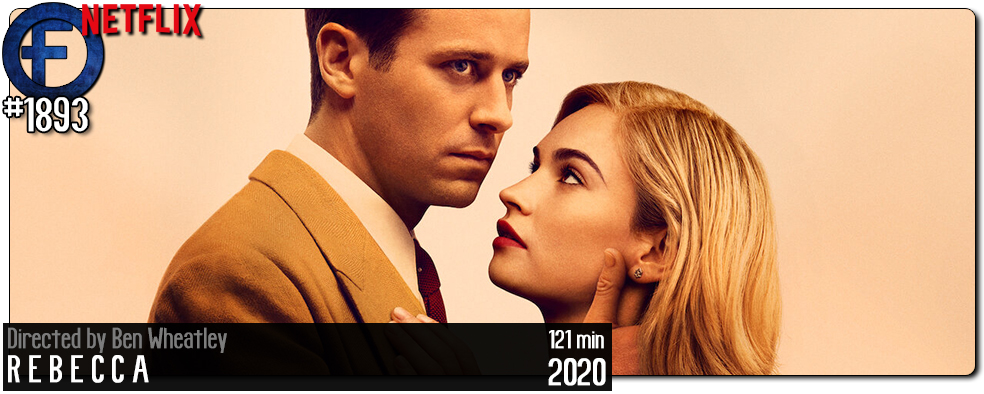

Principal Cast : Lily James, Armie Hammer, Kristen Scott Thomas, Keeley Hawes, Ann Dowd, Sam Riley, Tom Goodman-Hill, Mark Lewis Jones, John Hollingworth, Bill Paterson, Ben Crompton.

Synopsis: A young newlywed arrives at her husband’s imposing family estate on a windswept English coast and finds herself battling the shadow of his first wife, Rebecca, whose legacy lives on in the house long after her death.

********

English director Ben Wheatley turns his considerably stylish attention to Daphne du Maurier’s classic literary horror Rebecca – popularly blessed with cinematic greatness prior to this version thanks to the masterful direction of Alfred Hitchcock – and delivers a stately, visually sumptuous but emotionally empty film that trades on the beauty of Lily James and the pre-cannibal (alleged) hunkiness of Armie Hammer without summoning the psychological torment the novel delivered so astutely. It’s not that Wheatley doesn’t treat the material with reverence, because he does with a sense of operatic camerawork and captivating production value, and neither does his cast deliver performances unworthy of the status of such a literary icon, for they are all absolutely excellent, but there’s a blandness, a distance between viewer and film that forces Rebecca’s 2020 iteration to succumb to mediocrity in such an intangible way it’s hard to put to words.

A young twenty-something unnamed woman (James – The Dig, The Guernsey Literary & Potato Peel Pie Society) is wooed by recently widowed aristocrat Maxim De Winter (Hammer – Call Me By Your Name, Mine) whilst on holiday in France, with the woman a dutiful aide to the dowager Mrs Van Hopper (Ann Dowd in superb form). After a whirlwind romance Maxim takes his new bride to his palatial British estate, Manderley, to live. The new Mrs De Winter’s life isn’t all cozy, however, for Maxim harbours a deep grief over the tragic passing of the previous Mrs De Winter, and is prone to outbursts and fits of rage, abetted by the sinister Mrs Danvers (Kristen Scott Thomas – Gosford Park, Darkest Hour), the housekeeper who continually reminds the new Mrs De Winter that the previous holder of that title was a woman of infinite beauty, staggering grace and astounding social import. When clues to the previous Mrs De Winter’s death start to resurface, however, Maxim’s new wife must hold her nerve against the omnipresent shadow of isolation to protect her new husband and her new way of life.

At first blush, Ben Wheatley’s Rebecca is a sumptuous, faithful retelling of the original text. It’s impeccably cast, produced superbly (the Manderley mansion depicted in the film was shot over no fewer than five British estates doubling for various portions of the De Winter home) and has some scathing, witty and incredible dialogue. By all accounts, it should have been a slam dunk knockout. That it isn’t is a puzzle; it’s one of those rare films in which all the parts work superbly, all the elements are in sublime concert, and yet the film feels decidedly average, a lesser movie than what you might expect. Wheatley, who has directed some absolutely bizarre films in his career – A Field In England, High-Rise and Free Fire are each bonkers in their own unique ways – takes a swing at the psychological horror subgenre and ever so quietly misses the mark, although not for lack of trying. Elements of the genre are present, including frantic nightmare-dream sequences and moments of exquisitely nail-shredding tension, but the film never really clicks.

The plot is predicated on the dynamic between the unnamed woman (the Narrator of du Maurier’s novel) and the scabrous Mrs Danvers, here essayed sublimely by the always-terrific Kristen Scott Thomas, glowering and wither-gazing her way through a performance directly inside her wheelhouse. For me the film works less well when it’s focusing on the relationship between Maxim and his new bride, which is where I think a lot of this Rebecca’s performative ambivalence originates. Hammer and James have a nice on-screen chemistry but their characters’ respective emotional states doesn’t generate audience empathy enough to solidify their appeal when things turn to shit in the third act. Deliberate obfuscation of Maxim De Winter’s motivations and his impenetrable grief are intended to frustrate the audience via the gradual mental breakdown the new Mrs De Winter undergoes as her self-doubt and feelings of isolation and inadequacy grow, but this frustration doesn’t pay off as well as it needs to to satisfy an audience clamouring for understanding. Lily James’ role of honouring that inadequacy is well handled by the actress but with limited success by Wheatley. Had the film spent more time dealing with the interplay between Mrs De Winter and Mrs Danvers as the latter continually tried to belittle and diminish the former, through the shadow of the dearly departed first Mrs De Winter looming over all, Rebecca could have worked a lot better as a psychological thriller. Wheatley’s decision to equalise the three main lead roles perhaps didn’t service the story’s inherent sinister tones as well as intended.

As I mentioned, the cast are all very solid here. Hammer and James are excellent with their material, Kristen Scott Thomas is malevolence personified, doing more with a glint in her eye than most actors can do contorting themselves into a pretzel, and the great Ann Dowd, Sam Riley and Mark Lewis Jones, the latter playing the local prosecutor charged with the case of the recovered body of the former Mrs De Winter in the film’s second half, are all commendable and thoroughly enjoyable supporting players. Even the more minor roles, such as Keeley Hawes as Maxim’s sister, John Hollingworth as Maxim’s brother-in-law Giles, and the briefly seen but thoroughly memorable Jane Lapotaire, as Maxim’s embittered grandmother, give the film width of character and a little more canvas to paint its story upon, regardless of how insufficient that painting is. You never feel that there’s any stunt-casting going on; everyone suits their respective roles and deliver largely flawless performances of the material.

In terms of its behind-the-camera proficiency Rebecca wants for little. Wheatley’s cinematographer-du-jour Laurie Rose, who has shot all of the director’s films to-date, as well as Overlord, Stan & Ollie, and the recent Pet Semetary remake, gives Rebecca a lustrous, well-conditioned-hair look, awash in brown and golden tones for the early French-set sequence before transitioning to the shadowy, gloomy Manderley narrative with a crisp, realistic flavour. The widescreen aspect ratio is used to considerable effect in key moments of the film, notably when Maxim and the Narrator are driving through France in his car, and also when the Narrator begins to have her mental state fracture under constant strain, while one of the most tension-filled moments comes as Lily James’ character has to try and hide from the police’s impending arrival as she’s sneaking through a doctor’s rooms in the third act. There’s a loveliness to the film’s photography, personifying the heady early days of first love and romance before descending into the spiral of madness Rebecca’s concave plot elicits. Clint Mansell’s accompanying score is also excellent, a moody, brooding work underscored by the associated visuals but never overt or overpowering. Among the film’s most impressive feats is the stunning costume design, throughout which a lot of the film’s subliminal subtleties entangle the viewer. Maxim’s business-like sports coat and debonair holiday dressings give way to a more formal attire once back in Manderley, whilst Lily James has the pleasure of being robed in the film’s luxurious gilded dresses and sensual, innocently provocative outfits. Kirsten Scott Thomas cuts a formidable figure in her monochromatic clothing choices and it entirely suits her character.

I think whilst Rebecca remains an on-the-surface faithful retelling of the original text, a lot of the subtext du Maurier inserted is befuddled, or absent. One of the story’s more salacious allusions was that Mrs Danvers was secretly in love with the former Mrs De Winter, her rage and grief personified in the film’s potentially shocking climax, which isn’t really delivered with the same proximity as that afforded in Hitchcock’s version. The reason Mrs Danvers is so grief-stricken over Rebecca De Winter’s tragic demise seems more to do with their deep, lifelong friendship than anything more promiscuous, which (in my opinion) robs the emotional gravitas of the flaming finale of an added prickle of sorrow. Subtext is everything in these early literary works – could you imagine had du Maurier uttered the word “lesbian” in her novel that it would have ever seen print? Nope. Rebecca feels empty of subtext, despite Wheatley’s attempts to sauce things up by pretending there is any.

Look, I’m not going to pretend Rebecca was some great classic or even a gigantic misfire, because in many, many aspects it’s a delightful, if taciturn, work of mystery and psyche-horror. Wheatley does miss the mark more often than he hits, sadly, which leaves the film meandering through amiableness instead of the potent mind-games shenanigans I was hoping for. With all the elements of Hollywood working in its favour – great story, terrific cast, equally wonderful production and technical values – it’s frustrating to see how little Rebecca actually affects the viewer with this bland, mediocre result. Not awful, certainly not amazing; Rebecca is worth a look for completists but it won’t be one you’ll rush back to time after time.