Movie Review – Hurricane, The (1937)

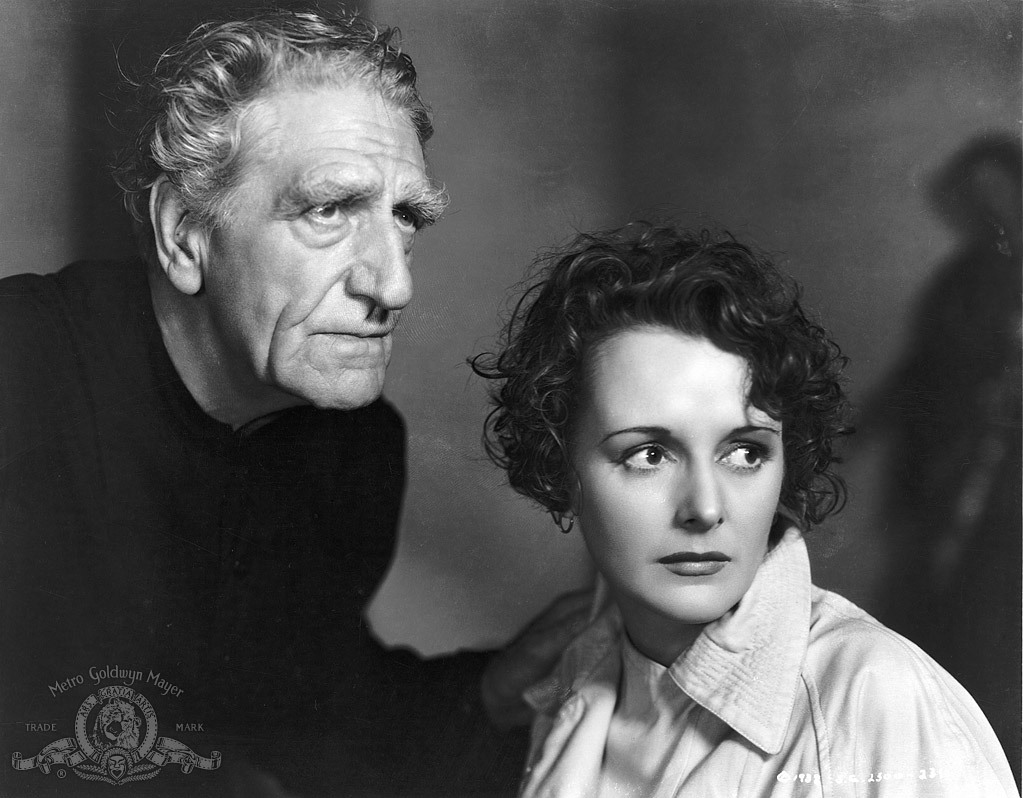

Principal Cast : Dorothy Lamour, Jon Hall, Mary Astor, C Aubrey Smith, Thomas Mitchell, Raymond Massey, John Carradine, Jerome Cowan, Al Kikume, Kuulei De Clercq, Layne Tom Jr.

Synopsis: A Polynesian sailor — unjustly imprisoned after defending himself against a colonial bully — is relentlessly persecuted by his island’s martinet French governor.

********

Few filmmakers are held in the highest of regard quite like Hollywood icon John Ford. The renowned director is considered one of the greatest to step behind a camera, telling both fictional and non-fiction documentary stories during his lengthy career. Before he would snag an Academy Award for Best Director (How Green Was My Valley), Ford helmed a significant number of (now mostly lost) silent films as well as 1937’s The Hurricane, a tremulous little romance-drama masquerading as a visual effects spectacle, a film which scored three Oscar nominations in technical categories and for Thomas Mitchell’s supporting role of an island doctor. Sadly, The Hurricane is merely a trifle, a meandering romance and ethical conflict narrative mixed with the impending onset of one of nature’s most fearsome weather events, the titular hurricane winds which threaten to wipe a small Pacific island nation off the map.

On the tiny fictional Pacific island of Manakura, lovers Terangi (Jon Hall) and Marama (Dorothy Lamour) live in relative peace whilst their nation is under occupation from the French. Terangi works as a First Mate aboard a local schooner with Captain Nagle (Jerome Cowan), whilst Marama lives an idyllic life as a wife and eventual mother to Tarangi’s child. Following a violent encounter with a boozy white man, Terangi is sentenced to six months prison by the governor, Eugene De Laage, against the protestation of all including his wife, Germaine (Mary Astor), the island’s doctor, Kersaint (Thomas Mitchell), and missionary pastor Father Paul (C Aubrey Smith). After several escape attempts lengthen his sentence, Terangi is set upon by the cruel and vindictive warden (John Carradine), until finally making his way to freedom thanks to the help of locals. Just as he is reunited with Marama after years away from his family, Manakura finds itself in the path of a deadly tropical hurricane, with rising tides and incredible winds threatening to sweep the tiny island and all its inhabitants into the sea.

Although I came to The Hurricane appreciating the lustre of John Ford’s typically astute eye overseeing it, the film left me feeling indifferent to its charms. One part romantic interlude, another part prison escape thriller, and backing up the Hollywood Vault of Money to produce a truly eye-opening final hurricane sequence that puts even the expensive tribulations of Dorothy in Kansas to shame, The Hurricane has many plot points to work through, however it does so with a cumbersome, overly sombre tone, and I enjoyed it only a little. It’s also one of those films told from the outsider’s perspective; the Polynesian aesthetic established within the film’s sense of distant romance slants towards the viewpoint of the occupying force of French colonials, who see themselves as intellectual superiors brining order to the relatively savagery of the tiny island nation. Hell, even the two central leads, Terangi and Marama, are portrayed by non-ethnic white actors – Jon Hall and Dorothy Lamour, the latter finding herself in an early “before she was famous” role as the doe-eyed beauty Tarangi spends his time pining for in prison – which causes some contextually appropriate cringe given today’s politically correct climate, but remembering the time in which The Hurricane was produced it’s hardly surprising.

The film’s script is credited to Dudley Nichols and Oliver Garrett and is based on the novel of the same name by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall, more famous for writing the immediately classic Mutiny On The Bounty. Approaching similar subject matter dealing with the law and those who break it, The Hurricane’s approach to its subject matter is a cross between Tarzan and FW Murnau’s similarly oceanic Tabu: A Story of The South Seas, only with a little more White Man Anger in place. While Jon Hall’s Terangi might be the chiselled-abs hero of the piece, a large portion of the film’s antagonism comes from Raymond Massey’s French Governor role, an initially sympathetic De Laage who, through perhaps the pressure of dealing with being governor or the torment of having one prisoner decide to make a break for freedom continually. Massey’s performance is solid, at times truly frightening, although it should be said that the constant refrains and protests from those closest to him, including his wife played by a delightful Mary Astor tend to wear thin quite quickly. Massey is backed up by C Thomas Smith as the elderly yet faithful pastor, Thomas Mitchell as the slightly drunk but equally faithful doctor, and Jerome Cowan as the captain of apparently the only schooner sailing the Tahitian seas.

The refrain purveyed through the film’s first two-thirds is that of “the Law” and “justice” being at odds with Terangi’s rebellious island-life ways; French law is different from Island law and therein lies the rub. This brings into conflict Terangi, who becomes a hero of his people, and De Laage, who becomes a vilified dictator of sorts, and a man whose dark shadow looms large over the back end of the film’s climactic hurricane sequences. Their embittered rivalry is largely one-sided, with Terangi only desiring to return to the arms of his beautiful wife and their young child Tita (Kuulei De Clercq). Their reunion is brief, however, for the film’s final twenty minutes is devoted to one hell of an action-effects sequence: John Ford’s replication of a torrential hurricane is a sight to behold, a violent ruction in island life filled with death and despair amid the prayer of Father Paul and the wailing of the poor Manakura people. Truthfully, The Hurricane spends a large portion of its running time looking at Terangi and De Laage’s conflicted relationship and shatters all that with the gusting winds of nature’s beast, a precursor to today’s disaster epics with big-screen appeal and technical exceptionalism, only the payoff doesn’t quite work. The previous hour of dramatic work doesn’t click, doesn’t sing with the precision of the film’s terrific effects later on, the overall effect being one of a film split in two by compromising narrative trajectory.

While it feels like it takes an eternity to get to, when the hurricane does strike it’s a ferocious, deadly event that likely shocked audiences of the day and boggled the minds of young people who may have seen it. The realization of the physics of a hurricane on a low-lying oceanic island are terrifying, with rising tides and winds capable of uprooting trees and unstable huts tearing across the screen with implacable menace. A mix of practical sets and well filmed model works, coupled with some tragic acting performances from those characters killed or injured in the lengthy sequence make the climax of The Hurricane a truly remarkable assault of cinema’s visual potency, with Ford sparing no viewer the agony of characters they’ve enjoyed in the previous hour or so suddenly meeting their demise with perfunctory cruelty. That Ford managed to make even the supporting roles effective within this deadly consequence as he does is testament to his skill as a filmmaker, and his representation of the picturesque locale as an endearing, bucolic destination is one of remarkable lightness of touch. The contrast between arcadian living and the horror of an apocalyptic weather event has rarely been to profound as it is here.

As great as the film’s final sequence is – the one you’ve all paid to see – it’s quite the ordeal getting there. Terangi’s prison escape escapades run out of steam quickly, as does the continued reflection on lawbreaking by De Laage, and by the time the hurricane does arrive you’re almost kinda glad it does. The dramatic weight of the film isn’t enough to support such strung out angst, although it is sufficient enough to bring moments of sorrow as Manakura is effectively wiped off the Earth. The performances are largely forgettable despite John Ford’s glamorous monochrome cinematography, and the sense of impending doom never arises like it ought early enough to generate the required tension in the latter half of the movie. The Hurricane is a mildly diverting piece of entertainment overall, worth a look for those John Ford completists but few others. Its wind-blown work didn’t do it for me like I’d hoped, and I was left feeling ambivalent to the story.