Movie Review – Gangs Of New York (2002)

Principal Cast : Leonardo DiCaprio, Daniel Day-Lewis, Cameron Diaz, Jim Broadbent, John C Reilly, Henry Thomas, Liam Neeson, Brendan Gleeson, Gary Lewis, Stephen Graham, Eddie Marsan, Alec McCowen, David Hemmings, Lawrence Gilliard Jr, Cara Seymour, Roger Ashton-Griffiths, Barbara Bouchet, Michael Byrne, John Sessions, Richard Graham, Giovanni Lombardo Radice.

Synopsis: In 1862, Amsterdam Vallon returns to the Five Points area of New York City seeking revenge against Bill the Butcher, his father’s killer.

********

Boasting a legitimate all-star cast, Martin Scorsese’s violent, breathtaking depiction of mid-19th Century New York City is a scabrous, delectable, vicious canvas of debauchery and wantonness underpinning the then-nascent infant democracy in its birth pangs. Gangs of New York is led by the remarkable Daniel Day-Lewis (Lincoln) in the central role of the heinous gang leader Bill The Butcher, whilst Leonardo DiCaprio (Titanic) aligns himself with the tragic hero role of the film in Amsterdam Vallon, the young son of one of Bill’s former rivals. Set in the squalor and poverty of an area known as the Five Points – what is primarily now Chinatown and bisected by Mulberry Street – within New York City’s lower East side, Scorsese’s film is a tale of prejudice and social inequality, of a powderkeg society rife with corruption and vice, and makes for compelling viewing in almost every regard.

New York City, the mid-1800’s, and the crime-ridden slums of Lower Manhattan have given rise to various gangs controlling districts of the newfound metropolis. Among them, the “Natives”, led by the vicious Bill The Butcher (Daniel Day-Lewis), and the Irish immigrant Dead Rabbits, led by Priest Vallon (Liam Neeson – Taken), fight for control of the territory – the Dead Rabbits are vanquished, however the young son of the slain Priest, who watches his father’s murder at the hands of Bill, survives and is taken to an orphanage on Blackwell’s Island. Returning many years later, Amsterdam Vallon (Leonardo DiCaprio) ingratiates himself into Bill’s gang through the friendship of Jimmy Sirocco (Henry Thomas – ET: The Extra-terrestrial), in order to carry out a long-held dream of revenge against the gangster, however his burgeoning romance with pickpocket Jenny Everdene (Cameron Diaz – Charlie’s Angels), and having to navigate the various corruptions within the local constabulary (John C Reilly – Talladega Nights) and political factions (Jim Broadbent alongside Eddie Marsan) and the blithering influence of the high society types from Midtown (David Hemmings – Gladiator), make exacting his vengeance a tricky proposition indeed.

Director Martin Scorsese has perhaps done more for New York City’s image within the global consciousness than any filmmaker before or since; iconic movies such as Taxi Driver, Mean Streets, Bringing Out The Dead, Goodfellas, and more recently The Wolf Of Wall Street, have become so synonymous with the Big Apple through various generations there’s no denying the director isn’t intimately associated with the city’s pastiche of history and criminality. 2002’s Gangs Of New York is arguably Scorsese’s most corpulent film about the famous metropolitan settlement, a staggering ensemble essaying an epic, political, social and demographical examination of New York’s early days as both a hotpot of democratic birth pangs and a funnel for immigrant tensions, writ large on the eponymous Five Points conclave in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Violent, scattershot, occasionally emotionally engaging, with some terrific (and one terrible) lead performances alongside a solid supporting roster of British and American talent, Gangs Of New York is “prestige” Scorsese at his best, a tale of real people fantasised within the master director’s historical landscapes and worshipfulness of America’s blood-soaked past.

Written by Jay Cocks, Stephen Zaillian and Kenneth Lonergan, Gangs Of New York partitions an intimate story of revenge against the backdrop of a violent New York City, a potted history lesson given expensive production values at the hands of a cinematic maestro. The film explains the political landscape of the time, the various social mores and hypocrisies of such a varied populace living in such close proximity to one another that violence and intrusion are a matter of course, whilst the sullied and sordid mud-soaked streets of the Five Points form the central pivot around which much of Bill The Butcher’s reign of terror hinges. Tribalism and a sense of fascistic nationalism were (and still are, really) rampant in New York of the time, as Irish settlers fleeing the extreme famine in their homeland seek greener pastures and more opportunity in the land of the free. Most of the problems stem primarily from religious differences, with Roman Catholics, Irish Protestants, and innumerable secondary belief structures forming the basis for a lot of the violence depicted therein; you kinda have to hand it to mankind, we really are a stubborn, oafish bunch when you consider that a lot of the tribalism of today is rooted in the exceptionalism of the past.

The first thing that strikes you about Gangs Of New York is its stunning production design and visual extravagance. Obviously Scorsese has no ability to travel back in time and shoot in the real New York of the 1850’s, so the filmmakers replicated an enormous section of the city’s streetscapes and portside vistas at Cinecitta Studios in Rome, to opulent effect. The destitute alleyways and “streets” – little more than gaps between effluent-stained slums – come to life thanks to Michael Ballhaus’ stellar cinematography, lush colours and lurid textures really popping with vibrancy against the grime and grit of life in America at the time, and coupled with superb costume design really drag the viewer into this violent, hyperbolic world. There are a few CG effects layered onto some parts of the striking visuals to add immediacy to specific shots (some fire effects in the film’s climactic mass riot sequence leave little to be desired) but from what I could tell the vast majority of the film eschews the digital realm and strives for realism through practical photography and doing everything in-camera. Depending on your viewing ability – the film is available on a terrible Netflix stream, or on the far superior BluRay format – Gangs of New York looks truly sumptuous, a no-expense-spared film endeavour that picks the scab of New York’s history and lets it bleed.

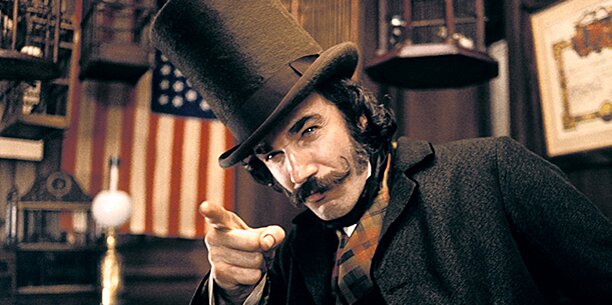

Stepping up to deliver magnetic performance inside this rousing acting spectacle is, of course, Daniel Day-Lewis. As Bill the Butcher, a character based loosely on the real-life William Poole, it’s an on-screen fireball that again solidifies my belief that Daniel Day-Lewis is perhaps the greatest actor alive today – at least of his generation. The malignancy of the Butcher’s presence in New York’s streets is omnipresent, there’s no tendril of influence that cannot be traced back to this powerful gang leader, and it’s Day-Lewis’ frenzied, belligerent, withering turn that keeps the audience hooked. If there’s ever an example of an actor truly inhabiting a role, look no further than Daniel Day-Lewis’ take on Bill The Butcher in Gangs Of New York, it’s that good. How he lost the Oscar for Best Actor to Adrian Brody that year still baffles me.

Stepping up alongside Day-Lewis is DiCaprio, who plays the older Amsterdam Vallon with a sense of hidden heartache and stirring, white-hot anger. Although DiCaprio looks far too pretty to be a dirt-smeared gang member with redemptive qualities, the actor delivers a meaningful and captivating performance even though he’s occasionally outshone be even the supporting cast Scorsese dots around him. Amsterdam Vallon is an intriguing Count of Monte Cristo type character, playing the long revenge game, and DiCaprio’s committed performance is arguably one of his best. Supporting roles to Henry Thomas, Jim Broadbent (as Tammany Hall boss William Tweed), John C Reilly as a corrupt local policeman, and Brendan Gleeson as mercenary for hire Monk McGinn, flesh out the various wax-and-wane narrative complexity of the film’s bulging extravagance, while bit-parts to David Hemmings, Stephen Graham, Liam Neeson (as Amsterdam’s ill-fated father and catalyst for the story’s violent trajectory), Michael Byrne and Eddie Marsan are nice little “hey it’s that guy” moments that feel organic and realistic within the aesthetic of the film.

The film’s biggest failing – about its only one, really – is Cameron Diaz as Jenny Everdene. Miscast badly, Diaz looks completely at sea against her far better acting peers, lost within her terrible accent and lacking a shred of chemistry with on-screen romantic interest in DiCaprio. She tries to bring her A-game to the role of a local pickpocket and is weirdly beholden to the Butcher’s charms, but the actress never looks comfortably suited to the role at any stage, despite all her considerable effort. Similarly to DiCaprio, maybe she is just too pretty for the hard-bitten, tragic Everdene, and at this point in her career the actress lacked the screen presence to truthfully present as dirty, downtrodden and salacious without looking like she was trying too hard. Every time she’s on screen, save for one momentary sequence towards the end of the second act, the film grinds to a halt and the viewer is brought out of the film simply because she’s not believable. Her scenes with DiCaprio, of which there are many, are risibly clumsy, with not even Scorsese’s mighty hand behind the scenes able to create a silk purse out of a sow’s ear.

Gangs of New York is a terrific, if heavily fictionalized, film, a masterclass in period storytelling and an example of near across-the-board perfection in casting. Daniel Day-Lewis’ scorching performance as Bill the Butcher, serviced superbly by DiCaprio’s beautiful looks and committed acting style, as well as gutsy supporting work from Henry Thomas, Brendan Gleeson and Jim Broadbent, almost hobbled by Cameron Diaz in a woeful turn, leave nothing on the table with this tragic, violent, historically fantastical fable about New York’s birthing process. While the film doesn’t appear to take sides in political, demographic or religious ideas other than presenting them as human failings simply and ingloriously, Gangs Of New York’s violence and depravity, its sense of hopelessness amid the mud and blood that soak the streets, the desolate human misery adjacent to pompous luxury, offer a glimpse into an America not to dissimilar to the one we see today.

To me, however, it’s the films final sequence that bears the most emotional fruit: the gradually deteriorating graves of both Bill the Butcher and his arch-nemesis, Priest Vallon, in a Brooklyn graveyard, overlooking Manhattan through the decades as the city grows and changes (a wonderful montage set to U2’s “Hands That Built America”), as if to suggest that all their toil, all their energy spent hating and fighting for power, is for naught against the inexorable grind of time and historical amnesia. Gangs of New York is a wonderful Scorsese film that remains as potent and emotionally gravitating now as it did in the aftermath of 9/11, which delayed the film’s release by almost a year.