Movie Review – Godfather, The

Principal Cast : Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, James Caan, Richard Castellano, Robert Duvall, Sterling Hayden, John Marley, Richard Conte, Al Lettieri, Diane Keaton, Abe Vigoda, Talia Shire, Gianni Russo, John Cazale, Rudy Bond, Al Martino, Morgana King, Lenny Montana, Johnny Martino, Salvatore Corsitto, Richard Bright, Alex Rocco, Simonetta Stefanelli, Tony Giorgio, Angelo Infanti, Franco Citti, Joe Spinell, Corrado Gaipa.

Synopsis: The aging patriarch of an organized crime dynasty in postwar New York City transfers control of his clandestine empire to his reluctant youngest son.

********

A towering landmark of American cinema, Francis Ford Coppola’s Best Picture Oscar-winning film The Godfather remains an enduring classic, nostalgically sitting alongside Citizen Kane as arguably the greatest film ever made. Its legacy is impossibly wide, its scope and breadth of characters impeccably cast and written, and the production value for a film made in 1972 sumptuous and hypnotic. It is regarded by the most astute cinema lovers as a masterpiece, and yet fewer and fewer people have found their way into its charms some fifty years hence; modern reviews continue to propose the question of its quality resonating in today’s more cynical age, a question not without merit but one which, when viewing The Godfather even now, remain preposterously antiquated considering the indelible struggle of loyalty, family and the rise of power within the halls of the reputable Corleone crime family.

In Post-war New York city, 1945, Italian crime boss Don Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando) runs his criminal organisation from his sprawling estate in upstate New York City, assisted by eldest son Sonny (James Caan) and consigliere Tom Hagen (Robert Duvall), as well as long-time loyal associates Clemenza (Richard Castellano) and Tessio (Abe Vigoda). Sonny is a hot-headed, hungry leader who wants to take on the mantle of his father, that of Godfather, whilst Vito’s middle son, Fredo (John Cazale) is less reliable and sent to run a casino in Las Vegas. Returning from the War, the youngest of the Corleone brothers, Michael (Al Pacino) arrives at the family estate with his girlfriend Kay (Diane Keaton) in tow, and is thrust into the seedy underworld of the mob when rival families attempt to assassinate Vito whilst he is out shopping. With corrupt cops (Sterling Hayden) and vicious enemies (Al Lettieri and Richard Conte) all around, and Sonny threatening to shoot anyone who comes close, Michael finds himself back in Sicily, in hiding, as the heat from his shocking revenge bubbles up. Eventually, with Don Vito returned home to recuperate, Michael Returns and takes his tragic place at the head of the powerful, ruthless Corleone family.

It’s impossible to critique The Godfather and its legacy in Hollywood’s echelon of success without recognising first both the Mario Puzo novel from which it’s Oscar-winning screenplay (by author Mario Puzo and director Francis Ford Coppola) is derived, but also the long, storied, instantly mythological mafia crime families that ran rampant throughout America during the late 19th and early 20th Century, particularly along the Northern and Eastern borders – although the mob was prevalent throughout most populated urban landscapes, including Chicago, Los Angeles and Las Vegas, nowhere personified the ruination and legend of the Sicilian Mob moreso than its influence on New York City, bolstered by increasing numbers of Italian immigrants relocating to the Big Apple. Puzo tapped into the prevailing love-affair America had with the mafioso with his hugely successful book (like the film, spawning a series of sequels), and delivered upon the world arguably the most defining iconography the mob underworld had ever seen on the big screen. Themes of family loyalty, of corruption and a multitude of memorable lines of dialogue would course through the film, a violent, operatic dramatic liturgy of responses by the various underworld figures in the story; rarely has a film so encapsulated an entire legendarium of criminality and made it so astoundingly sexy and terrifying all at once.

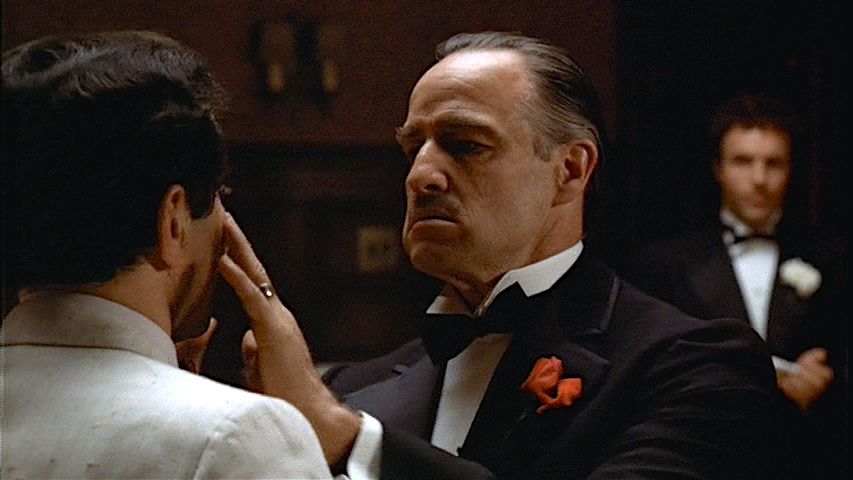

Nominated for eleven Academy Awards, including three Supporting Actor turns for James Caan, Robert Duvall and Al Pacino in their respective roles, and eventually winning three, The Godfather appears to have elevated itself into the Hollywood firmament by remaining well within the conversation for Greatest Of All Time for the entirety of its fifty years of existence. Aside from the superb screenplay, which balances delicate character beats, brutal and swift bloody violence, and a mournful, almost melancholy refrain for a lost sense of gentlemanly criminality, The Godfather is led by some powerhouse performances from its stellar, white-hot cast. Brando, who would snag the Best Actor gong (before refusing the accept it, in one of the Academy’s more controversial moments), is sublime as Vito Corleone, the ageing Don who leads with wisdom and cunning as he engages in the politics of mob life, from dispensing justice through bribery or scandal, or even ordering people be killed in order to further his family’s gain. Brando’s monologues, particularly his distinct delivery of Coppola’s engorged dialogue, are effortless for the actor, reminding us (yet again) why he was one of the preeminent screen talents of his generation.

He ain’t alone here, however: Al Pacino embodies quiet menace as he gradually assumes power once his brother, the equally memorable James Caan, is removed from the picture. Caan, who is basically angry for the entire film, embodies the hot-blooded Italian temper with supreme nuance, turning his initially fractious simmering temper into a tragic, almost fatefully Shakespearean symbol of despair. Quietly inhabiting the go-between role betwixt real-world and mafioso lifestyle is Robert Duvall (who would go on to appear in Coppola’s Vietnam epic Apocalypse Now a few years later), and while he may exhibit a degree of restrain as to the actions surrounding him, is the film’s “in” for the casual viewer. While Tom Hagen may not be a blood member of the Corleone family, Vito (and Michael) treat him as an adopted child and his role as consigliere, the family’s lawyer and “fixer”, is a significant player in the game. Pacino, Caan and Duvall deserved their Supporting Actor nominations (I would even go as far as to suggest Pacino deserved a Lead Actor gong alongside Brando) and it’s legitimately shocking none of them won. The rest of the supporting cast is a who’s who of Italian or mobster character actors – Richard Castellano (Incident On A Dark Street, The Gangster Chronicles) plays a loyal associate of the Corleone family, a violent man who is as cuddly and rotund as he is bloodthirsty. Richard Conte, Al Lettieri, Alex Rocco and Angelo Infanti play a variety of supporting roles that widen the tableau upon which Coppola unspools his story, a mixture of religious iconography, postcard-perfect lifestyles (a lengthy opening sequence involving Vito’s daughter, Connie (a wailing Talia Shire) marrying her non-Italian boyfriend (Gianni Russo) juxtaposes the loving family celebrating whilst Corleone meets with those who seek his advice and assistance in various mobster ways) and a sense of impending collapse of the entire house of cards is a heady mixture.

Enveloping the moral ambiguity of the characters within the story is the fascinating cinematography of the legendary Gordon Willis. Willis’ photography on The Godfather is a wonder, his use of lighting, shadow and a palpable sense of drab dread throughout the US-based footage is intriguing, whilst the sun-drenched hills of the Sicilian countryside are a literal heavenly respite by comparison. New York, from the Corleone estate to the drizzled, dank streets of Manhattan, are almost oppressively presented, an isolating, incomplete characterisation mirroring the tortured violence depicted by the story. Even places of relative warmth, such as a restaurant Michael finds himself invited to by the duplicitous Sollozzo and the corrupt police chief McCluskey (Sterling Hayden), are soaked in sourness, making the habitation of the city almost a tragic act in and of itself. Representations of Vegas and Los Angeles at various points throughout the film are equally as embittered, as if the intrinsic darkness of the mafia follows Michael or Hagen wherever they lurk. Willis’ cinematography skews deftly towards brown and deep yellows a lot, soft darkness creeping into the edges of the film as out characters dwell in their thick-walled mansions and fortress-like estates. The drabness of the film’s visual palette deftly echoes the slowly rotting humanity within the Corleone family, as violence and acts of evil – assumed under the nomenclature of “business” – eats away at their moral and ethical fabric.

Despite clocking it at nearly three hours, at no point does The Godfather ever feel slow or treading water. Coppola, together with Oscar-nominated editors William Reynolds (The Sting, The Day The Earth Stood Still) and Peter Zinner (The Deer Hunter, A Star Is Born), have crafted a film that luxuriates in its characters and settings, and takes its time to develop both them and the ongoing story of betrayal and offers too good to refuse, without allowing them to become boring. It helps that you have a stable of world-class acting talent to work with in the editing bay, with a quintet of Oscar-calibre performances anchoring this sprawling, protracted timeframe mythology, and where the film doesn’t lean as heavily on Brando alone but rather allows each Corleone man an individual arc and time to spare in becoming an iconic character in and of themselves. The film isn’t squeamish with its violent content either: The Godfather has long been the defining mafia crime film due to its honest depictions of death and carnage. From the assassination of James Cann’s Sonny at a tollway, to Pacino’s Michael murdering both Sollozzo and McCluskey in cold blood, to the film’s climactic takedown of all of the Corleone family enemies, Coppola seems to delight in graphic blood and violence in moments of loud brutality. Death isn’t pleasant, somebody once said, so why should it be so on film: The Godfather truthfully indicates how mob justice and turf wars escalate leaving a bloody trail of corpses behind. For what? At no point do you ever feel the time drag, or the film grind to a halt, which is rare in a film of such length when every minute in the presence of these odious yet eminently watchable characters is made to count.

The Godfather absolutely earns the status of one of Hollywood’s all-time great films. It is a legitimate masterpiece, as often as that word is bandied about making it seem inconsequential to suggest as much. With themes of corruption and corpulent luxury pervading every frame, the fascination with the mob remains as strong and alluring as it ever has been, the “honour among thieves” subtext remaining fixated on the tragedy of the death following in the family shadow. Towering performances by Brando, Pacino and Caan, together with a fabulous and often surprising supporting roster of perfectly cast actors in a variety of roles, make for one hell of a strong movie experience that resonates to this day. The Godfather is essential viewing for anyone claiming to be a fan of film, and stands as a moving work of art that deserves all the plaudits and praise it continues to receive.