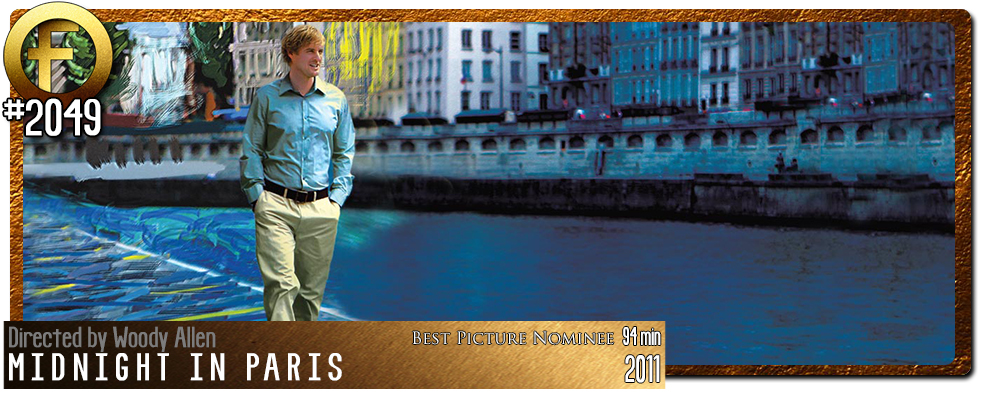

Movie Review – Midnight in Paris

Principal Cast : Owen Wilson, Rachel McAdams, Marion Cotillard, Tom Hiddleston, Alison Pill, Corey Stoll, Adrien Brody, Kathy Bates, Michael Sheen, Nina Arianda, Carla Bruni, Kurt Fuller, Mimi Kennedy, Lea Seydoux.

Synopsis: While on a trip to Paris with his fiancée’s family, a nostalgic screenwriter finds himself mysteriously going back to the 1920s every day at midnight.

********

Whimsical, infatuated love-letters to Paris don’t come along often enough, in my opinion. Woody Allen’s last truly great film, Midnight In Paris is exactly the kind of lightweight, easy-going fare I’ve come to expect from a director known for his verbose characters and esoteric scenarios, rightly nominated for Best Picture despite the breezy, nostalgic glow pervading almost every frame of this simplistic, delightful movie. Led by an always-engaging Owen Wilson being magically transported back to 1920’s Paris each evening, the film’s adoration of period pop-culture figures and zeitgeist intellectualism is an unfettered cultural delight, with a soupy and at times soft-focused romanticism enveloping a troupe of surprising cameos and guest stars that – as is always the case with Woody Allen’s films – feel somewhat analogous to the director’s own anxiety-ridden sensibilities.

Successful Hollywood screenwriter Gil Pender (Wilson) is on a trip to Paris with his materialistic fiancée Inez (Rachel McAdams) and her disapproving parents, John (Kurt Fuller) and Helen (Mimi Kennedy). Whilst there, they bump into one of Inez’ old friends, the arrogant and egotistical Paul (Michael Sheen) and his wife Carol (Nina Arianda), who accompany them on various sightseeing trips through the city. Late one evening, Gil is alone in the winding streets of the city, when he is whisked away to a party attended by none other than famous 20th Century novelist F Scott Fitzgerald (Tom Hiddleston) and his socialite wife Zelda (Alison Pill); he has such a grand time he finds it difficult to believe he has been transported back to 1920’s Paris in its heydey, meeting a variety of popular artists, novelists, playwrights and musicians each evening, but falls for the mistress of painter Pablo Picasso, Adriana (Marion Cotillard), with whom he finds a bond of affection. Through his visits to the past, Gil also meets American novelist Ernest Hemmingway (Corey Stoll), painter Salvador Dali (Adrien Brody) and fellow cultural titan Gertrude Stein (Kathy Bates), while in the present he also finds a kindship with street-vendor Gabrielle (Lea Seydoux), over old Cole Porter records.

Woody Allen is a director who typically writes what he knows, and as with the majority of his output he knows himself all too well, injecting his specific insecurities into his scripts and often turning his main character into a proxy version of himself, or at least aspects of himself as he presents to the public. At times charming, sometimes aggravating, with every Woody Allen film you can kinda see the cogs turning as the writer-director auteur briskly adapts his feelings towards further understanding the human experience. Midnight In Paris works as a weird evocation of historic nostalgia, a ruminative elicitation of a bygone era thought to be a “better time” by Wilson’s pensive Gil Pender, and for whom this time stands as the pinnacle of artistic freedom and expression. Allen throws in a buffet of notable figures of the period, often in Google-worthy cameos so very brief you might almost miss them – composer Cole Porter, acclaimed Spanish filmmaker Luis Bunuel, surrealist artist Man Ray, and TS Eliot make for a sprawling accoutrement of famous names, although Allen does sprinkle in some lesser known lights just to spice up your Wiki search, and it adds intrigue to the tableau presented for the fantasy.

Paris has such a romantic aesthetic it’s easy to see how one might become enamoured with it to such a degree – Gil’s absorbing strolls through the tree lined boulevards on both banks of the Seine come with inbuilt affection for the City of Love, for anyone who’s ever visited it. Rachel McAdams’ Inez, who finds the city’s sprawling cabal of cafes, bohemia and historical significance a high class bore, is less circumspect about Gil’s lustrous feelings to Paris, finding his romanticised notions of living there in an attic to write his troublesome first novel problematic for their relationship. The angst and troubled partnership between them is always destined for disaster – and it is – with Gil’s trips to the past putting into perspective his life in the present. I’ll be honest, the how of the film’s magical transportive narrative isn’t as important as is the who, notably the magnetic screen presence of Marion Cotillard, who portrays Adriana with an aloof, almost aristocratic indifference until she meets and gets to know Gil, a far more affable man than those she typically affiliates with.

The rapport between Owen Wilson and Cotillard is the soul of the film, and Allen does his best work keeping them together on screen as long as humanly possible. Wilson’s gibbering Gil Pender is a typical mess of insecurities and feelings of missed opportunities, but the actor’s easy-going charm and straw-chewing affability maintain a romantic interest alongside Cotillard’s sensual elitism. McAdams’ role is far more ephemeral than I expected her to be – a blasé mix of selfishness and narcissism create a character easy to find repulsive and, to a lesser degree, befuddlement as to how a successful writer like Gil has ended up with such a pontificate bitch. Michael Sheen’s equally egocentric character, with whom Gil has multiple problems of personality, is architecturally the film’s chief villain, despite not being an outright “bad” person in the sense that he does things with premeditated evil in mind, and the actor carries the role well. Tom Hiddleston and Corey Stoll make for terrific avatars of the real-life people they portray, and Kathy Bates is an blast every minute she’s on the screen (which, I’ll lament, isn’t often enough!). Lea Seydoux, whilst having a relatively minor role, is a luminous beauty and augments a key moment late in the film in which Gil’s love-affair with bohemian-era Paris seems to climax in reminiscence.

Midnight In Paris never explains itself. It doesn’t have to; much like the Parisian hoi poloi depicted in the film, it exists as an exemplar of art for art’s sake, a nostalgic poetry as evocative as any creation delivered by the characters depicted within. The cobbled streets of a time-worn city are shrouded in the opulence and the decadence of the early 20th Century (as well as France’s Belle Èpoque, a notable period of liberal thinking and great innovation prior to World War I) and Allen’s keen observational humour fits neatly into that Bohemian sense of intellectual exploration; never has a film felt more attuned to its writer’s motivations and in directing this, Allen once more affirmed himself as a tragic artiste writ large. One suspects the mournful stories of many of the artists he writes into his film here feel somewhat to his own real-world tribulations, in the sense that out of human sadness comes great art – whether you agree with him or not. Midnight In Paris is a fabulously quiet film of simple ideas, a great premise and Owen Wilson’s most engaging, enigmatic performance to-date, and if nothing else reminds us all why we fell in love with Paris in the first place.