Movie Review – All The King’s Men (1949)

Principal Cast : Broderick Crawford, John Ireland, Mercedes McCambridge, John Derek, Joanne Dru, Walter Burke, Anne Seymour, Shepperd Strudwick, Ralph Dumke, Katharine Warren, Raymond Greenleaf, Will Wright.

Synopsis: The rise and fall of a corrupt politician, who makes his friends richer and retains power by dint of a populist appeal.

********

Of the four films to bear this title, three (including this one) are based on Robert Penn Warren’s 1946 novel of the same name, and only one has won Best Picture at the Academy Awards. Robert Rossen’s incendiary adaptation of Warren’s novel is less pleasing as an ensemble piece and most assuredly a career-defining one for star Broderick Crawford, who rightly snagged the Best Actor Oscar for his turn as Willie Stark, a rural politician who makes it big in the state legislature before corruption and graft threaten to tear him down. It’s a story that rings as powerfully true today as it did back in 1949, with seemingly nothing having changed if you cast your eyes over the current crop of United States political aspirants. While some of the acting and dialogue is a little stodgy, and poorly dated, the underpinning human narrative is as overwhelmingly tragic as it has ever been, mirroring not only political life at the time – the central character was reportedly analogous to one-time Louisiana Governor Huey Long, who was assassinated barely a decade prior in 1935 – but also today, showcasing the corrosive power of, well, power corrupting even the most pure-hearted and aspirational individuals.

Willie Stark (Broderick Crawford) is charismatic and populist political aspirant in America’s Depression Era Deep South; entering politics with the intention of seeing off the corrupt structure of governance of the day, Stark initially fails in his attempt to court the people’s vote. He is followed by journalist Jack Burden (John Ireland), himself from a wealthy family, and acidic secretary Sadie Burke (Mercedes McCambridge in her Oscar-winning Supporting Actress role) and Jack’s girlfriend Anne Stanton (Joanne Dru). After studying law, Stark eventually succeeds in winning office, portraying himself as a virtuous man of impeccable honour and loyalty. However, as the years wear on, Stark soon becomes beholden to his own power, desperate to retain the offices he believes are rightfully his, even to the detriment of his own family – his wife Lucy (Katharine Warren) and son Tom (John Derek) soon come to resent him – and it’s not until he is impeached for his crimes that the moral arc of the universe, while long, bends towards justice.

In an era where every political figure is eventually mired in scandal and corruption, All The King’s Men gives off quite a dispiriting tone. It’s the kind of story that works as a cautionary tale, if only more people heeded the film’s advice. Either don’t go into politics, or if you do, expect to be scrutinized every second of the day. Sadly, in the near-century since Robert Warren’s novel was published, very few political figures appear to have taken notice of the story’s prescient ability to strip away ostentation and deliver a simple message to all who hope to cling to authority: absolute power corrupts, absolutely. Willie Stark is a fictional character but whose journey to politics and eventual death by assassin’s bullet are incredibly similar to the life story of Huey Long, in what I would have to suggest is a very similar modus operandi to Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941), which was reputedly a knife-stab to real-life media magnate William Randolph Hearst, as truth being stranger than fiction. Rossen’s screenplay adaptation is filled with pickpocketed moments of Warren’s novel and he has ably captured the zealotry of pre-war American political life and crafted a well-acted, deftly directed piece of not-quite-fictional fiction that will sit uncomfortably with many inside the political spectrum.

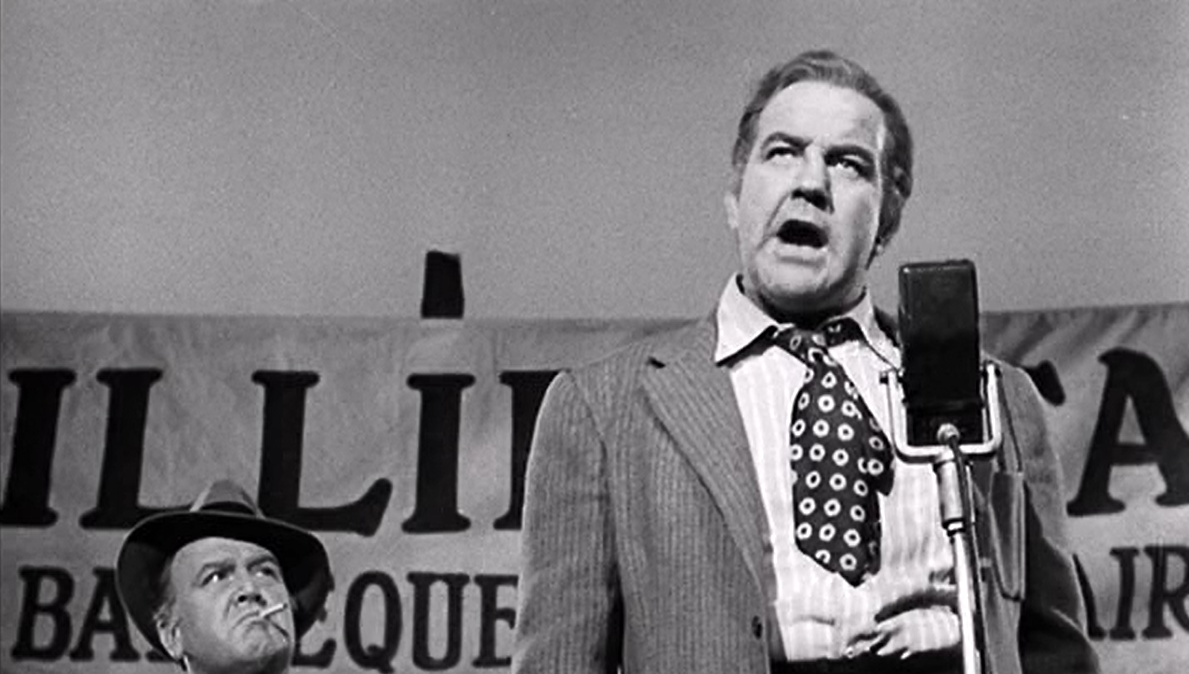

While All The King’s Men plays as an ensemble piece, and the entire cast are all eminently good in the film, this is undeniably a film shouldered by Broderick Crawford’s magnetic, larger-than-life performance as Willie Stark. Crawford described his looks as that of “a retired pugilist” and it’s fair to say that his half-bashed face and squinty eyes lent themselves to a kind of shifty egomaniacal visage as the film’s dark second half overshadows any of Willie Stark’s early good intentions. Crawford is a powerhouse here, a bludgeoning, bullish, bullying, braggadocio character of ill-temper and virtuosic slipperiness, as he slides deeper and deeper into the graft and sleaze of political life. It’s the kind of performance that literally fills the screen, towering over his co-stars with subliminal physicality as much as his thuggish jowls and piercing gaze tear strips off of anyone inside his proximity. There’s a ragged honesty to Crawford’s ability to switch between Good and Bad in Willie Stark, and the sad fact that modern politicians still use this kind of passive-aggressive approach to their careers will forever haunt this film’s legacy.

The rest of the cast are all uniformly good. John Ireland is excellent as the Jiminy Cricket of the film’s moral compass, Jack Burden, who recognises how far Stark is (or has) fallen but seems powerless to prevent it. Joanne Dru makes a solid fist of Burden’s girl, Anne Stanton, who eventually has an off-screen affair with Stark to the detriment of her relationships. As the tight-lipped and effortlessly sarcastic Sadie Burke, Mercedes McCambridge absolutely slays in her supporting role, a role I would have wished to see expanded such is her chemistry with the rest of the cast and her rapport with the material. Bit parts to Walter Burke, as Stark’s chief henchman Sugar Boy, John Derek as the tragic son of a gun, Tom Stark, and Raymond Greenleaf as a local judge only add quality to the already stuffed eloquence of the ensemble. It should be noted, however, that All The King’s Men feels a little anaemic with its use of the wider ensemble, however, with all bar McCambridge feeling a lot like they’re simply propping up Crawford’s bombastic lead role without really revelling in their own agency. In fact, nobody else has much of an arc beyond encircling the Willie Stark trajectory, which I found disappointing. Having said that, the film is still a gold class production across the board, and I think my issues with it stem more from a dated production aesthetic than anything specific to the casting.

Although filmed on various local Californian locations, there’s something insular about the film’s production value. At times, the dusty landscapes and period architecture look positively brilliant in Rossen’s camera, but equally so the film’s interior sets leave a lot to be desired, looking decidedly “studio soundstage” instead of realistic. I don’t know if that’s just me but this jarring effects of big-budget exteriors and cheaply-made interiors was a little discombobulating, and made for quite the whiplash viewing experience. Costume design was generally excellent (although in one scene, in which John Ireland and Joanne Dru are walking alongside a dock, Ireland is sporting a black and white cross-hatched coat that looks like it was just collected from a bargain big and thrown onto the actor without an iron ever making it to set) and the film’s cinematography is nothing if not complementary to the darker themes of the story. DP Burnett Guffey, who would go on to snag an Oscar for Bonnie And Clyde in 1967, uses light and shadow to initially illuminate and then cast into darkness Willie Stark and his ascent and descent into malfeasance, and his framing of many of the film’s sequences are jaw-droppingly beautiful.

Although written in 1946 and filmed here in 1948, All The King’s Men remains as modern and up-to-the-minute as any story can be, given the predilection of many public figures to gain authority and power and then do the absolute worst with it. While it may have dated poorly in some technical aspects, the performances and themes are as white-hot potent today as they have ever been, maybe even moreso for modern audiences jaded with political skewering by late night hosts and skit shows. Robert Rossen’s direction is excellent (he would lose the Best Director Oscar to Joseph L Mankiewicz for A Letter To Three Wives, one of only a few times Best Picture and Best Director haven’t gone together), as is the cinematography and costume design, and if nothing else is yet another torn-from-the-headlines story of power and corruption that warrants considerable re-evaluation.