Movie Review – Touch of Evil

Principal Cast : Charlton Heston, Janet Leigh, Orson Welles, Joseph Calleia, Akim Tamiroff, Joanna Moore, Ray Collins, Dennis Weaver, Valentin de Vargas, More Mills, Lalo Rios, Marlene Dietrich, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Harry Shannon, Mercedes McCambridge, William Tannen.

Synopsis: A stark, perverse story of murder, kidnapping and police corruption in a Mexican border town.

********

This review is based upon the Theatrical Version of Touch of Evil, edited under the supervision of Universal Pictures. A 1976 “Preview” version, and a 1998 “Restoration” cut are both longer and utilise edits dictated by director Orson Welles, but neither of these form part of this critique of the movie.

Director and Hollywood wunderkind Orson Welles’ seminal 50’s noir Touch Of Evil is a film of problematic origins, uncomfortable racism, and controversy, whilst also remaining as one of the best films to come out of America in the 20th Century. Welles, who also co-stars alongside Charlton Heston and a terrific-if-underused Janet Leigh (of eventual Psycho fame), fills this adaption of Whit Masterson’s “Badge of Evil” with energy and pace, some terrific camerawork, and manifests a sublimely entertaining noir film that delivers crisp characters and devilish thrills despite some uncomfortable production choices.

Touch Of Evil is set in an unnamed corrupt US/Mexican border town where a car bombing sparks a tense investigation. The story follows Mexican narcotics officer Mike Vargas (Heston), who, while on his honeymoon with wife Susan (Leigh), becomes embroiled in uncovering the corrupt practices of American police captain Hank Quinlan (Welles). As Vargas digs deeper, he discovers that Quinlan has been manipulating evidence and coercing confessions to maintain his control over the town. The tension escalates as Vargas’s pursuit of justice puts him and his wife in danger, leading to a climactic confrontation that ultimately exposes Quinlan’s corruption and brings about his downfall.

I have always admitted that film noir isn’t among my favourite cinematic genres. Typically, noir presents characters involved in criminal activity who aren’t necessarily your well defined protagonists or antagonists, more comfortable within a moral grey area that contrasts alongside all human failings; my strong preference is for films that present as prototypically binary in their Good Guys and Bad Guys, although this failing of mine notwithstanding, Touch Of Evil is definitely a capital-G Great Movie, if for nothing else than it’s Orson Welles at his most arrogantly Wellesian. Very loosely based on the 1956 novel “Badge of Evil”, the heated tension and simmering undercurrent of explosive confrontation percolate superbly well thanks to Welles’ terrific direction, abled inestimably by Russell Metty’s supreme cinematography. Welles also wrote the screenplay, so it’s no long bow to call this a possible vanity project for the great auteur, what with the obvious award-bait monologues and incendiary plot, characters and subtext generating a real sense of pushing the envelope. Sex, violence and corruption are the prime movers of any good film noir, and Touch Of Evil captures those aspects superbly.

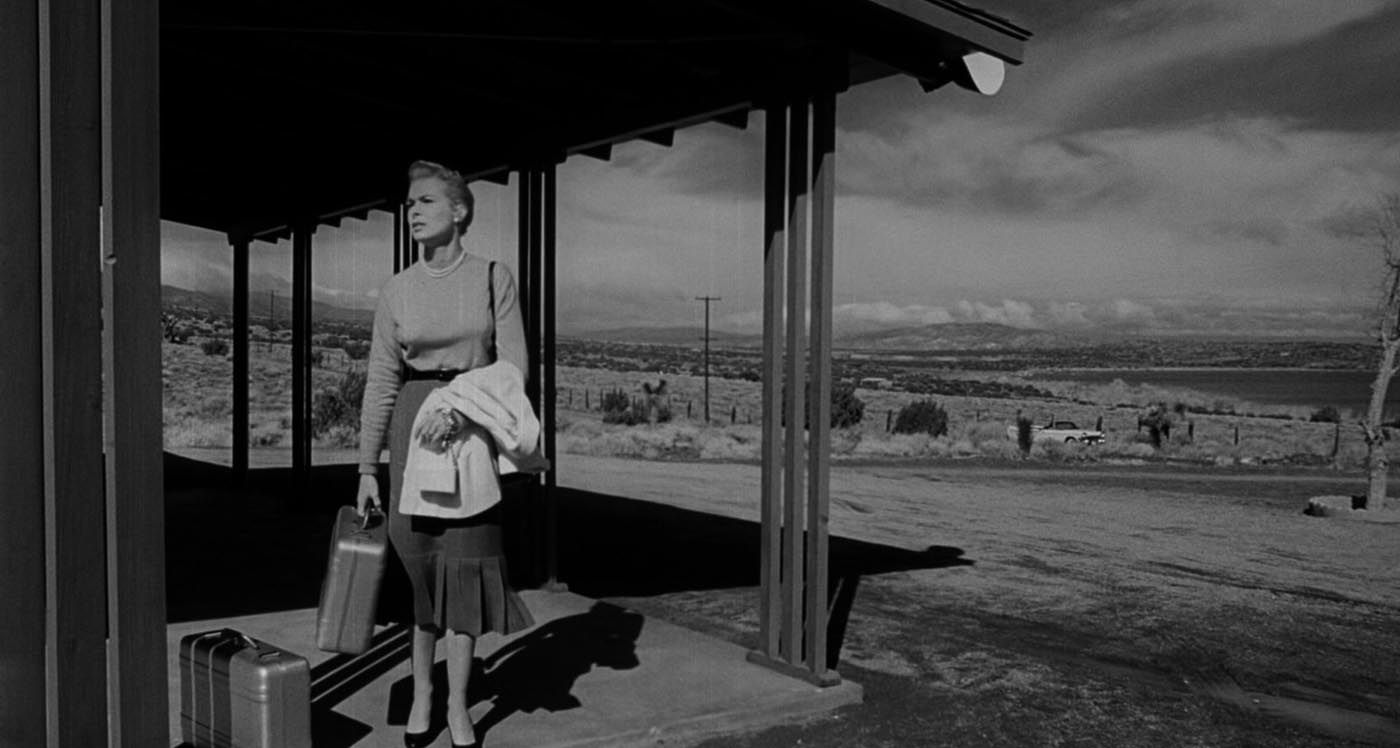

Although I’m unfamiliar with the conflict between the US and Mexico in which Touch of Evil takes its setting, Welles and his script give us just enough exposition to ensure a viewer some seventy years distant from the period can understand, if not entirely appreciate, the scope and subtext of what’s going on here. The racial profiling of American law enforcement has long been a thorn in the side of non-American inhabitants along the border and that – as it always does – forms a thunderous undercurrent of tension within the overall plot, to say nothing of the characters operating within it. Charlton Heston’s ubiquitous and straight-laced Mexican prosecutor Miguel Cargas, the film’s secondary focus despite being the quote-unquote Good Guy, is as provincially motivated and nationally upheld as any screen idol before him, although it should be noted that Heston was, in fact, not of Mexican heritage even the slightest bit. Despite a seriously problematic representation issue for folks of Mexican ethnicity, Heston’s character is arguably the strongest of the film overall, offering a square-jawed hero of non-white screen vintage that crackles with racial tension whenever the story demands his status be demonised. Janet Leigh, as gorgeous as she is, accepts the thankless task of being the un-fatale femme fatale of Touch of Evil, personifying virginal innocence despite not being a virgin, her fair white skin an almost ghostly presence amid the heat, stink and sweat of the town’s border-frontier tableau. While I definitely felt some chemistry between her and Heston as husband-and-wife, Leigh’s role slipped into the background of the films final half and became more a hinderance to my interest than a principal storyline I enjoyed.

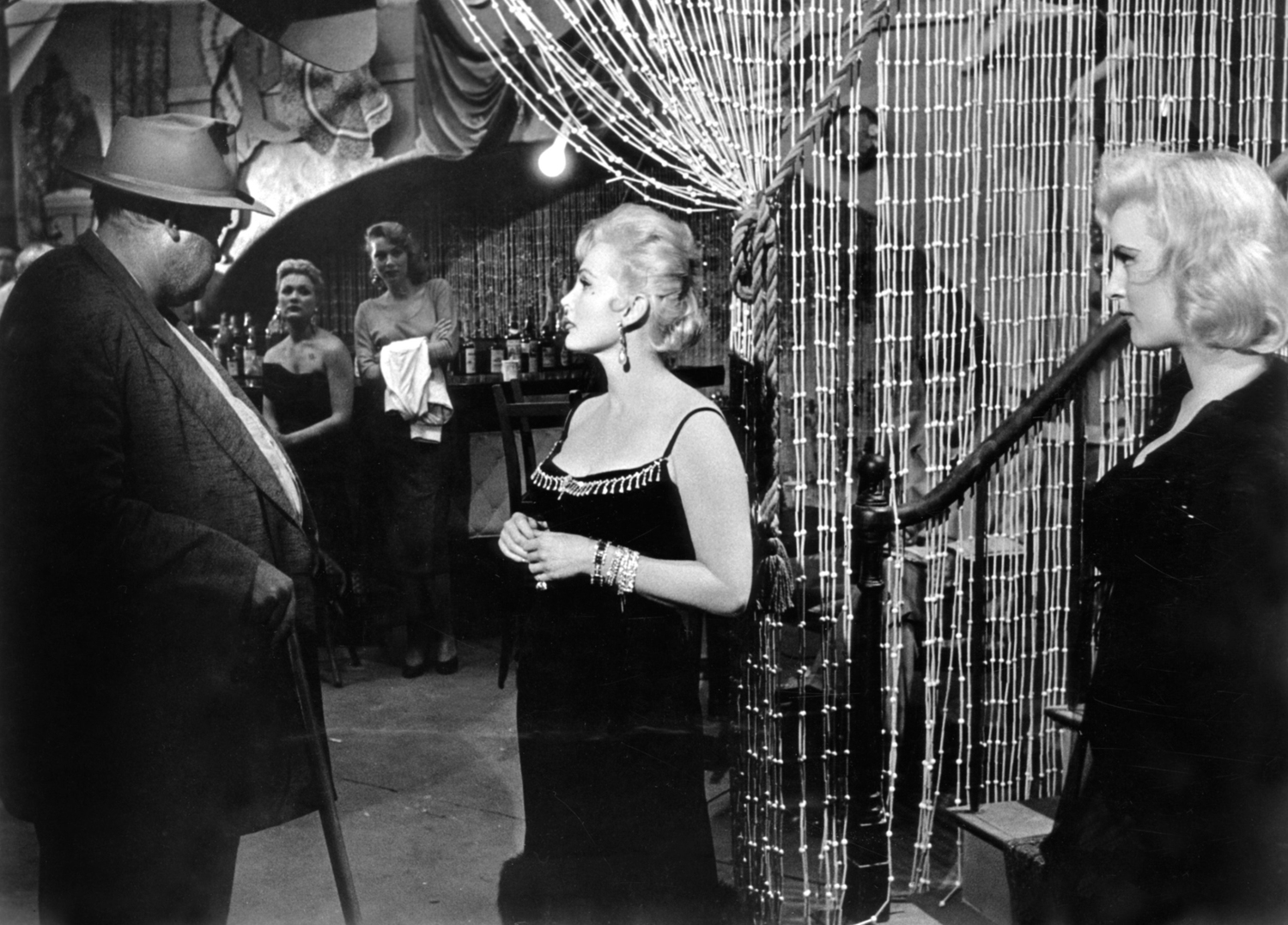

I would suggest, however, that it’s Welles himself, as the corpulent Police Captain Quinlan, an overbearing, corrupt, racist and odious individual who wields all-too-much power without compunction, who becomes the film’s “lead” character, and it’s a similarly dark role for the actor best known as Charles Foster Kane. If this was a modern film one might describe Welles’ performance in front of the camera as “unrestrained”, both literally and figuratively: Quinlan is an overweight, crippled alcoholic with a penchant for violence and beating the snot out of people to get his way, and you can rest easy knowing Orson Welles absolutely plays it up for all its worth. Welles’ large frame is amplified by the creative choice to often shoot the character from low angles, exacerbating his bulk and turning him into a literal boulder of evil dominating the screen. In almost every scene in which he appears, Welles ensures his face filled the frame – Universal matted the original framing from a standard square Academy ratio into the relatively newfangled 1.85:1 ratio, which is preserved in most home video formats available to watch that I’m aware of. This sense of hubris isn’t just Welles showing off, even though that much is obvious, but it really does work for the story in turning Quinlan into an almost iconic, unstoppable object of failed humanity wretchedly trying to maintain his grasp on power – power, mind you, to control as small border town, as much a showcase of Quinlan’s venality as it is his personal weakness.

The film is also populated by a gaggle of bit parts filling out the ensemble, including a terrific turn by Akim Tamiroff as a local Mexican crime boss, Ray Collins, and early Dennis Weaver (Duel) turn as a twitchy motel assistant, and the double-fisted lure of Zsa Zsa Gabor and Marlene Dietrich, the latter of whom feels inserted clumsily into the movie almost as product placement, while the former is a glorified and utterly wasted minor cameo. Other notable stars include Mercedes McCambridge (All The Kings Men), Harry Shannon (Citizen Kane), and perhaps the most sublime of them all, Joseph Calleia as Quinlan’s subservient cop buddy, Sergeant Pete Menzies. Even in the smaller parts, the film’s ensemble are all aces, creating intriguing sidebar red herrings for the plot proper to manoeuvre around.

For me, however, despite the story not really doing much for me (I admit, I did have trouble following exactly what was going on and why I was supposed to care about these people, reiterating the issue I have with film noir generally), the film’s strongest element has to be its production value and Welles’ terrific direction. It should be noted that Welles was famously pulled off the film’s post-production due to difficulties between he and the studio, not to mention issues with the edit being performed by Edward Curtiss, who would be replaced by editor Aaron Stell, before studio production lead Ernest Nims also took a stab at it, hoping to turn what was described as an “unwatchable mess” into something more coherent. Folks who’ve read my review of Welles’ posthumous film The Other Side Of The Wind will appreciate my disdain for hamhanded and lackadaisical flourishes in the editing room that discombobulate the viewer for no other purpose than to be pretentious; and let’s face it, Welles at his worst was the very definition of pretentious. By all reports the theatrical release of Touch of Evil was never overseen by Welles himself, although the famed director did dictate notes for Studio Head of Production Edward Muhl, who applied the relevant cuts to the film as indicated.

What stands out, however, is just how claustrophobic and terrifying a lot of Touch of Evil really is. The character work is magnified by Welles’ terrific use of deep focus (almost like the split diopter effects employed most vigorously by Brian DePalma) and incredible Dutch angles to tell the story, as much as visual language of its own to enhance the dialogue and often white-knuckle tension the finished film displays. The film pulsates with heat – be it the heat of violence, sex or corruption – and nearly every frame of the film somehow manages to exemplify this fact. The opening long-take, in which a bomb is placed in the truck of a car, a car that then drives through town passing a number of other vehicles, pedestrians and townsfolks, before exploding out of frame, is near-Hitchcockian in its ability to hook the viewer from the start, while a sizzling POV car ride through the alleyways and slums of the border town at-speed is startling for a genre of film that had always seemed contrived to use rear-projection for similar “driving” sequences. The framing of Welles as a giant among his on-screen co-stars is the director’s ego playing at full volume but, as I alluded to earlier, it serves a purpose to the story as well, so it can be forgiven. Yes, I think Touch of Evil is one of the most well-constructed series of images I’ve seen in a long time, and if we’re all honest with ourselves this is to be expected with anything Welles touches.

So I have no qualms in stating that Touch of Evil is a genuinely great movie. I do, however, have a real problem with Charlton Heston’s performance being done using brown-face, or at least a heavy spray tan, the equivalent of minstrels for Mexicans and perhaps the only legitimate complaint I have to the film. One might find it excusable to the degree the film was made decades before Hollywood progressivism but that doesn’t make it any less uncomfortable to watch, especially considering Heston’s work as a white Moses or Judah Ben Hur in years to come – blackface is as shitty now as it was then, it’s just that then it was still widely accepted. The effect of this is jarring, to say the least, although within the context of the film’s production and social norms of the day it’s justifiably problematic. It’s the only blemish on a film that delivers in almost every regard – writing, direction, acting, production design and cinematography, this is a typical Welles masterpiece that, while it’s aged poorly in some respects, is as strong a film noir as you’re likely to ever see. With caveats in place, Touch of Evil is essential viewing for fans of classic Hollywood.