Movie Review – Ben-Hur: A Tale Of The Christ

Principal Cast : Ramon Novarro, Francis X Bushman, May McAvoy, Betty Bronson, Claire McDowell, Kathleen Key, Carmel Myers, Nigel de Brulier, Mitchell Lewis, Leo White, Frank Currier, Charles Belcher, Dale Fuller, Winter Hall, Claude Payton (uncredited).

Synopsis: A Jewish prince seeks to find his family and revenge himself upon his childhood friend who had him wrongly imprisoned.

********

A remarkable film achievement, and celebrating it’s centenary year in 2025, and an opening salvo from then studio newcomer Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the silent epic adaptation of Ben-Hur is a masterpiece of the form and supremely captures the emotional resonance of General Lew Wallace’s 1880 novel of the same name. Although a troublesome production, and one of the most expensive film projects ever mounted at the time (the eventual budget in 1925 dollars was around $4m, equivalent to nearly $70m in modern terms, and a staggering amount of money to spend on a movie in those early days), there’s something so satisfying about Ben-Hur’s rip-roaring adventure, captivating central performances, and astounding production value, that I am shocked it isn’t discussed with more vigour in similar tones to Charlton Heston’s record-setting mid-century remake. I would go so far as to suggest this monumental silent film is arguably more accessible emotionally to audiences even now, with a spellbinding lead turn from Ramon Novarro as the title character, not to mention the astonishing reproduction of the story’s iconic chariot race, as well as its fierce sea battle between competing galleys on the waves.

The story follows the tumultuous life of Judah Ben-Hur (played by Ramon Novarro), a Jewish prince in Jerusalem who is betrayed by his childhood friend, Messala (Francis X. Bushman), now a powerful Roman officer. Accused of treason and sentenced to the galleys, Judah’s life is filled with hardship and endurance, but a fateful act of kindness towards a Roman general, Quintus Arrius (Frank Currier), leads to his adoption and rise to Roman nobility. Fuelled by his desire for vengeance, Judah eventually confronts Messala in the iconic chariot race, where both the personal and spiritual stakes reach a climax. The story is set against the backdrop of early Christianity, with encounters with Jesus Christ subtly woven throughout, influencing Judah’s path from vengeance to redemption.

Although touted as one of the greatest stories ever told, I’ve always found the 1959 William Wyler version of Ben Hur to be overly dry, far too serious, and unexpectedly drawn out. I get it, it’s a bible-adjacent narrative weaving a fictional contemporary of Christ into, around and alongside the well-known story of God’s only Son, and almost every take on Lew Wallace’s story is treated with utmost reverence because of it. In this respect, the 11-Oscar-winning Ben Hur is less a character-driven drama and more a spectacle upon spectacle, a distantly evocative period piece anchored by an equally dry, far too serious turn from Charlton Heston. As much as I respect what Wyler and Heston, together with some serious below-the-line talent achieved, I was hesitant that a two-and-a-half-hour silent film telling the same story might be just as impenetrable, if not moreso; thankfully, this early MGM epic is actually a brilliantly emotive, succinctly energetic and altogether more accessible version of Wallace’s narrative, led by the charisma-for-days turn of Ramon Novarro in the lead role.

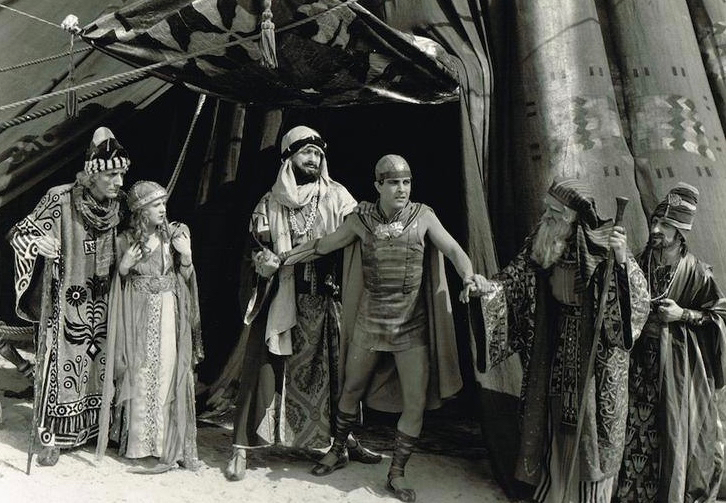

The 1925 adaptation, with screen credits to the writing skills of June Mathis, Carey Wilson and Bess Meredyth, delivers all the well-known moments of the Judah Ben Hur story: from the cruel stroke of fate in a roof tile falling on a pompous new Roman governor, to Hur’s castigation to row on a Roman galley for three years, through to the second-half chariot race and the eventual reunion with his long-lost family, there’s nothing new under the sun from a story perspective, and a lot of the key moments of the bigger, more widescreen-ier ’59 edition have their iconic genesis within Fred Niblo’s stylish direction. The caveat to that statement is that Ben-Hur: A Tale Of The Christ had an incredibly troubled – and protracted – production, with original director Charles Brabin not long into filming as well as a number of cast changes (Ramon Novarro was cast near the original production schedule’s completion, with producers jettisoning the original actor, George Walsh, for a reason I couldn’t confirm anywhere), and the wholesale up-and-move relocation of the sets and production from Rome to MGM’s backlot in Culver City. It’s hard to decide where Niblo’s direction and those who came before cross over, but part of me thinks it’s more to do with the legion of editors the studio put to work here than any single director or producer could handle. Don’t get me wrong: this silent film is absolutely epic, and boasts an enormous number of spectacular visual effects, action sequences and production design, but more than any version of this story I’ve seen to this point, the film has an equally satisfying emotional component that elevates it above all others.

Ramon Novarro is terrific as Judah Ben-Hur, the returning Jewish landlord whose sense of optimism at his status among the nobility of Antioch, a city on the southern frontier of modern-day Turkiye. He imbues Hur with a starry-eyed wonder and sense of self, something that comes into play as his character undergoes immense hardship through the course of the film, and its because of the actor’s innate screen charisma the film clicks from the moment he appears on screen. That particular point is about 18 minutes after the movie starts, carved into a glorified and seriously pious retelling of the birth of Christ, from Joseph and Mary’s arrival at Jerusalem to the Christ-child’s eventual crucifixion and the wrath of God laying waste to monumental structures in grief; had the film stopped there I’d say it was a technical masterpiece and jaw-dropping spectacle, but it’s only the start. Judah’s friendship with the stiff-backed Massala is handled beautifully, acknowledging both men have grown apart since they new each other years before, and Niblo’s editing team do a great job of building an early tension in their new differences. Papering over the racial prejudice of Massala’s disdain for the Jews in the Roman Empire does its job – when a roof tile accidentally falls atop the head of the incoming new Governor, Massala is quick to shackle Judah, his mother Miriam (Claire McDowell) and sister Tirzah (Kathleen Key) with unbridled guilt, sending Hur off as a slave while the women are cast into a pauper’s life through lack of money. This central conflict pervades the film’s opening half, and a bit of the second, until the famous chariot race brings both Hur and Massala together for their climactic showdown. Throughout, Navarro embodies Hur’s righteous sense of vengeance, a patient hopelessness given spark by a coincidental meeting with Hur’s former accountant, Simonides (Nigel de Brulier), and the emotional arc of Hur resounds more powerfully here than in any version I’ve seen.

I really had a great time with the mix of Christian and Roman mythology, and Niblo’s choice to intersperse some colour film stock into the monochrome footage is trailblazing – and effective. Although I’m hard-pressed to find a confirmation as to the nature of the creative choice behind this inclusion, given colour footage was arguably more expensive to achieve at the time, it seems as if Niblo utilised it predominantly (although not exclusively) for the moments in which Judah Ben-Hur runs into Jesus Christ, seminal moments in which Christ’s hand or arm are seen, or in which the son of God is otherwise obscured, and it’s a fascinating and thrilling effect viewing it as an amateur film historian. Niblo even recreates DaVinci’s iconic mural of The Last Supper, a gobsmacking moment of sublime religious proximity that takes one’s breath away; moments like this are sprinkled throughout the film, and they manifest a beautiful tableau of fervent desire to achieve some kind of enlightenment. The contrast between this and the more salacious aspects of the film’s production, including brief moments of topless women appearing on screen, are stark: given how religiously pious the film might appear, the aforementioned cowboy approach to the grubbier aspects of the film’s racial and prejudicial elements makes for genuinely sparkling storytelling. Some of the anti-Semitic underpinnings of Roman life are a touch hard to “enjoy” as it were, but for a story set during biblical times it’s apparent and on-the-nose.

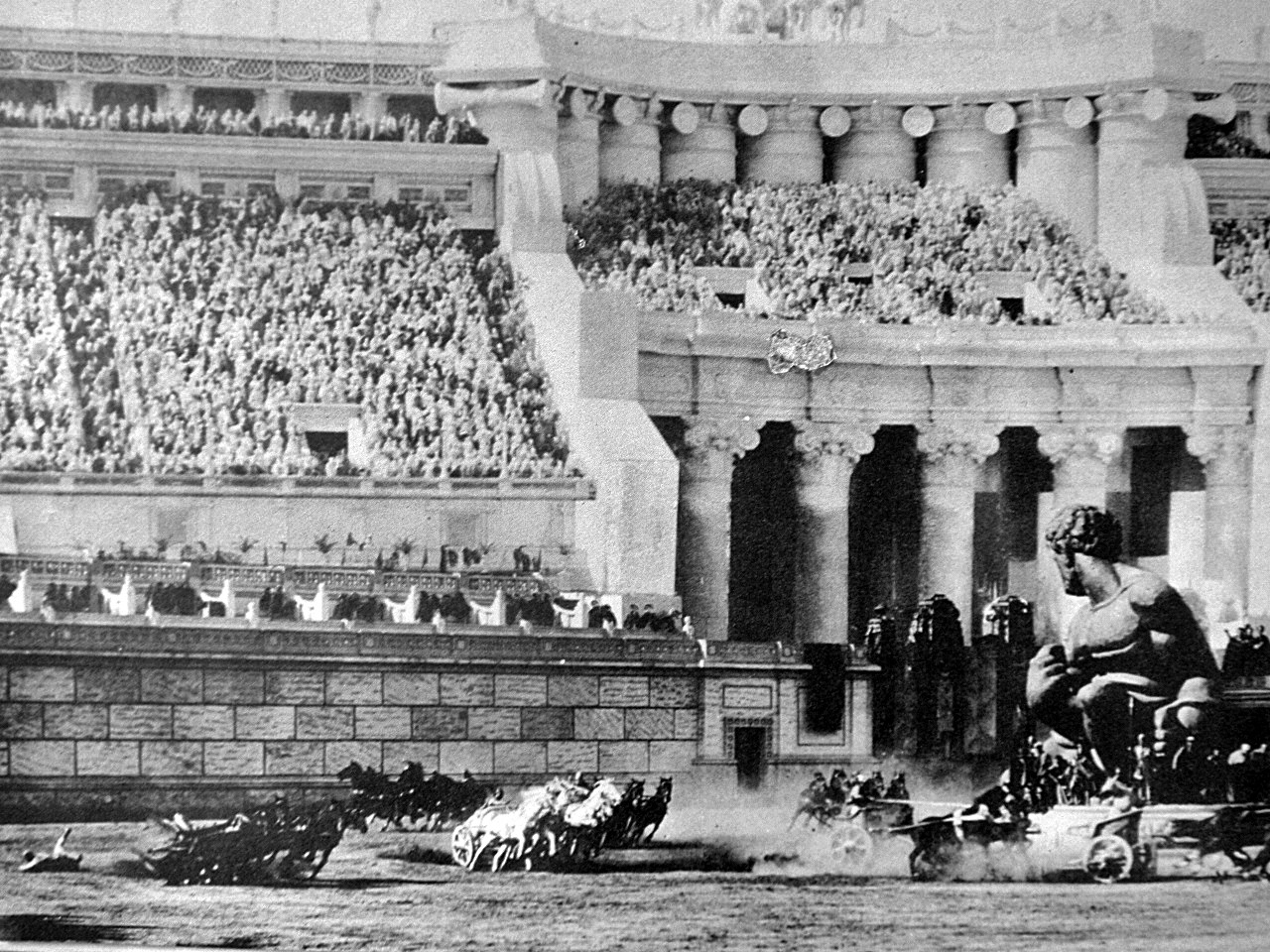

Arguably the film’s high-point, much like it is in the later Charlton Heston version, is the fabled chariot race, ostensibly between a gaggle of competitors but ultimately between Judah and Massala as antagonists. It’s here the film strides from excellent to positively stratospheric. The gargantuan sets, the violent actions of the race, the electrifying camerawork and astonishing editing choices, deliver one of the big-screen’s most memorable action sequences; little wonder filmmakers have been trying to copy it for decades, from George Lucas’ Star Wars podrace to any number of car, horse and plane chases the intervening years have given us. The sequence lasts some twenty minutes or so, kicking off almost without preamble and building, building, exploding into a frenetic, violent, cathartic event that had me goggling in disbelief. How they pulled this off in 1925 absolutely astounds me, there are modern films with all manner of technological wizardry who couldn’t manufacture the same stardust magic.

One of the cool things about Ben-Hur: A Tale Of The Christ is also one of the worst things about the film: made in 1925, the film personifies both the excess and unsafe methods of working in early-era film, in that everything feels like people’s and animals’ lives were put directly in danger while the camera’s rolled. There are stories of a large number of horses who had to be euthanised as the famous chariot race sequence was shot, due to a significant number sustaining injuries inflicted on purpose to achieve specific stunts, which is both cruel and desperately sad. There appear to be a number of real-life injuries sustained by human actors on the gargantuan galley boat sea-battle early on, although I could argue that that was less upsetting to me than knowing innocent horses found their film careers cut brutally short for our entertainment. This guerrilla methodology of filmmaking, a seemingly lawless cowboy approach to getting the footage, does make for utterly compelling viewing. While the limitations of 1920’s filmmaking are apparent, the sheer audacity of what the various directors, cinematographers and production designers put onto the screen is remarkable. It’s also testament (ha! a bible pun!) to the ingenuity of early filmmakers who made the impossible possible, from enormous models, double-exposures and what look to be matte work, as well as superb costume design and visual effects: the film is an absolute blast no matter how poorly you think of film without dialogue soundtracks. Of all the movies to declare themselves a sensational spectacle, particularly in these early days, the 1925 Ben-Hur currently sits as perhaps the definitive example of how to do it right.