Movie Review – Megalopolis

Principal Cast : Adam Driver, Nathalie Emmanuel, Giancarlo Esposito, Aubrey Plaza, Shia Labeouf, Jon Voight, Laurence Fishburne, Talia Shire, Jason Schwartzman, Kathryn Hunter, Grace VanderWaal, Chloe Fineman, James Remar, DB Sweeney, Isabelle Kusman, Bailey Ives, Madeleine Gardella, Balthazar Getty, Romy Mars, Haley Sims, Dustin Hoffman.

Synopsis: The city of New Rome faces the duel between Cesar Catilina, a brilliant artist in favor of an Utopian future, and the greedy mayor Franklyn Cicero. Between them is Julia Cicero, with her loyalty divided between her father and her beloved.

********

Debauched. Decadent. Opulent. Gorgeous. Francis Ford Coppola’s forty-years-in-the-making Megalopolis defies easy categorisation. Funded entirely by the director’s personal fortune and met with polarising reactions from those who ventured to see it, the film is a heady amalgam of futurism, historical homage, visual splendour, and Shakespearean melodrama. To dismiss it outright would be to do a disservice to its ambition, even if its narrative incoherence and conflicting subtext leave audiences perplexed.

My initial reaction on social media described Megalopolis as “an astonishing piece of confused cinematic hubris that will eventually become a cult classic,” and upon reflection, that sentiment holds true. The grandeur and audacity of Coppola’s vision are undeniable, but much like Tinto Brass’s reviled Caligula, this film’s brilliance is overshadowed by its excesses and baffling storytelling. It’s a kaleidoscopic fever dream of potential unrealised, its own inadequacies leaving viewers both awestruck and exasperated.

Set in the futuristic city of New Rome (formerly New York City), Megalopolis follows Cesar Catilina (Adam Driver), a Nobel Prize-winning architect who envisions a utopia called “Megalopolis”. Haunted by the tragic loss of his wife and battling his own demons of guilt and alcoholism, Cesar faces opposition from Mayor Franklyn Cicero (Giancarlo Esposito), a staunch conservative who prioritises immediate economic stability over lofty ideals. Complicating matters further is Cicero’s idealistic daughter Julia (Nathalie Emmanuel), whose shared dreams of a better world bring her closer to Cesar.

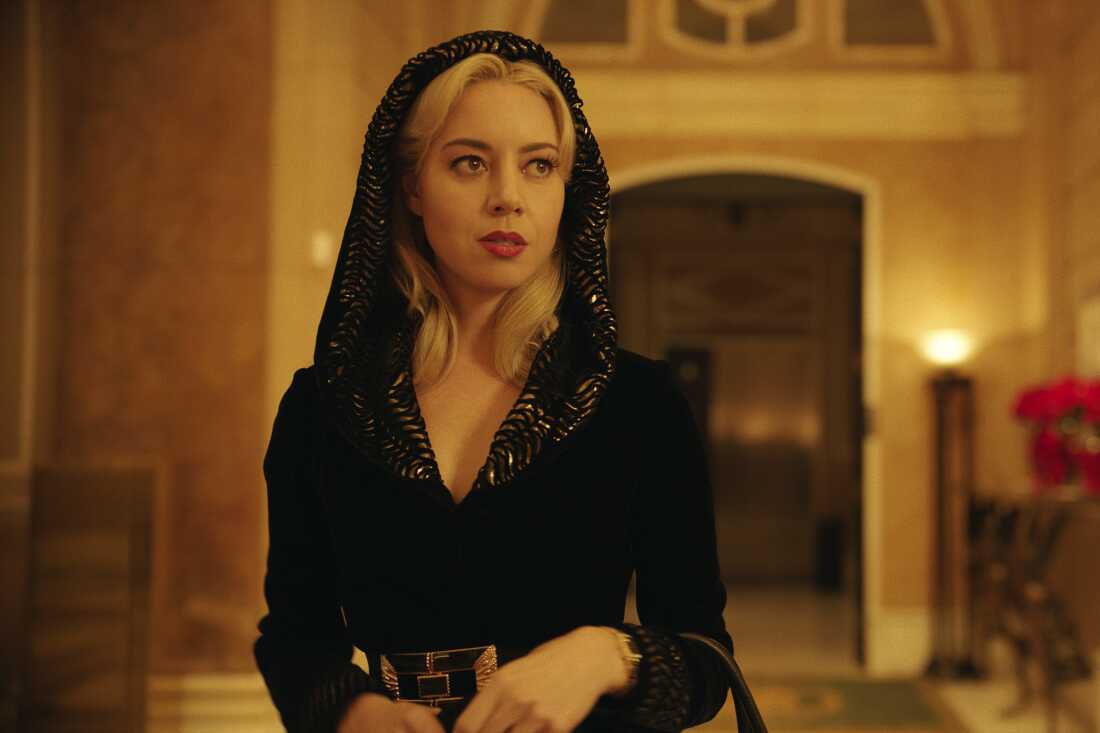

The supporting cast features a manipulative ex-mistress, Wow Platinum (Aubrey Plaza), who uses political intrigue to control Cesar; Hamilton Crassus III (Jon Voight), a frail but influential financier; and Clodio Pulcher (Shia LaBeouf), Cicero’s populist nephew who devolves into a dangerous demagogue. Amid these intersecting arcs of betrayal, ambition, and political turmoil, Megalopolis unfolds as an operatic battle for the soul of New Rome.

Coppola is a filmmaker with a singular vision, and his contributions to cinema—Apocalypse Now, The Godfather trilogy, and Bram Stoker’s Dracula—are the stuff of legend. That he personally financed this epic underscores his artistic audacity. Hollywood’s reluctance to embrace the project only highlights Coppola’s maverick status. Yet, the film’s production woes—ranging from VFX teams abandoning ship to last-minute rewrites—loom large over the final product. Indeed, the very creation of Megalopolis could serve as the basis for its own behind-the-scenes drama.

The visuals, however, are a triumph. Megalopolis is a sumptuous feast for the eyes, filled with salacious imagery and golden-hued cinematography reminiscent of both Metropolis and Coppola’s own Dracula. The world-building, inspired by Roman iconography and infused with post-9/11 subtext, is staggering in scale, yet the narrative struggles to match its ambition. Themes of idealism, pragmatism, and power collide in a discordant cacophony, leaving the viewer adrift in a sea of ideas. The plot, essentially a Romeo-and-Juliet tale with shades of political intrigue, suffers from convoluted subplots and underdeveloped characters.

Adam Driver delivers a magnetic performance as Cesar, his brooding intensity anchoring the film’s emotional core. Nathalie Emmanuel surprises with a heartfelt turn as Julia, while Shia LaBeouf gleefully chews the scenery as the venomous Clodio. Aubrey Plaza is mesmerising as the sultry, scheming Wow Platinum, her character exuding a playful menace. The rest of the cast—Jon Voight’s cringeworthy banker, Giancarlo Esposito’s stoic mayor, and Laurence Fishburne’s melodramatic narration—range from serviceable to superfluous. While the performances are committed, the script leaves many of these roles underutilised, their potential squandered amid the narrative chaos.

Despite its ambition, Megalopolis ultimately collapses under the weight of its own excess. Emotionally hollow and narratively incoherent, the film substitutes substance with spectacle, offering a barrage of breathtaking visuals that fail to mask its shortcomings. Coppola’s unrestrained ego—unfettered by studio oversight—results in a bloated, self-indulgent epic that lacks the discipline and focus of his earlier masterpieces. The thematic ambition of Megalopolis is admirable, but its execution is frustratingly inconsistent. The film wants to be everything at once: a critique of American exceptionalism, a meditation on utopia versus dystopia, and a grand love story. In attempting to tackle so much, it achieves little, leaving audiences to sift through a labyrinth of half-baked ideas and unresolved subplots. The final act, a chaotic montage that invokes the trauma of 9/11, feels particularly misplaced, an emotional gut-punch that lacks the necessary context to resonate.

And yet, for all its flaws, Megalopolis is a fascinating failure. Like a modern-day Caligula or a Terry Gilliam fever dream, it revels in its own audacious insanity. Coppola’s refusal to compromise is both the film’s greatest strength and its fatal flaw. The sheer scale of his vision, combined with the messiness of its execution, ensures that Megalopolis will be remembered—not necessarily for its quality, but for its sheer audacity. In the end, Megalopolis is a film I cannot wholeheartedly recommend, yet one I believe will inspire endless debate. It’s the kind of cinematic disaster destined for cult status, a midnight movie marvel that invites audiences to marvel at its excesses while shaking their heads in disbelief. Coppola has delivered a magnum opus of unparalleled ambition and hubris, a work that embodies both the best and worst of auteur-driven filmmaking. For that reason alone, it deserves to be seen—even if only once.

This review is right on the money! I remain overwhelmed by its scope, ambition, and failure to be comprehensible. Still, a must see!