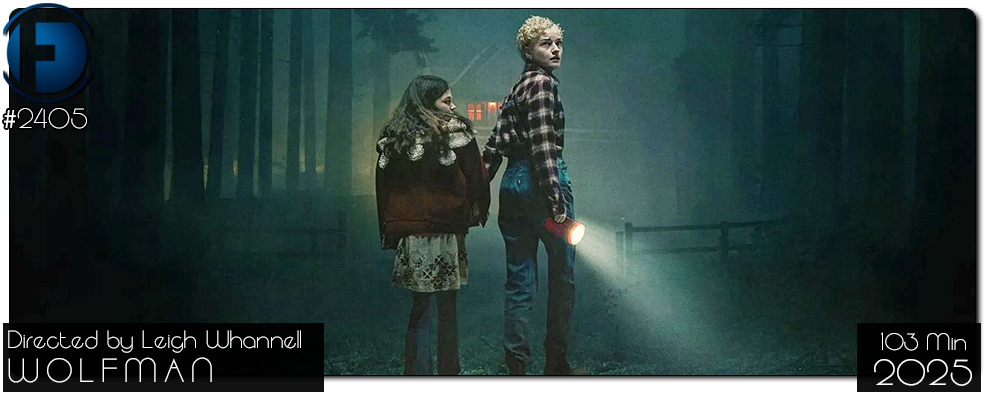

Movie Review – Wolfman (2025)

Principal Cast : Christopher Abbott, Julia Garner, Matilda Firth, Sam Jaeger, Benedict Hardie, Zac Chandler, Ben Prendergast.

Synopsis: A family at a remote farmhouse is attacked by an unseen animal, but as the night stretches on, the father begins to transform into something unrecognizable.

********

In the fifteen years since 2010’s Benicio del Toro-led The Wolfman, the gradual soft reboot of Universal’s Monster Cinematic Universe has eked out sporadic box-office success. With The Invisible Man director Leigh Whannell’s remake of the 1941 classic The Wolf Man, originally starring Lon Chaney Jr and Claude Rains, the studio aims to revitalise the iconic horror lineage using the very best effects modern filmmaking can offer. Unfortunately, Whannell’s sombre, suffocating effort is a turgid misfire—a cloying mix of atmospheric setting, unlikeable characters, and a ponderous, stuttering pace that irritates more than it terrifies. Despite the pedigree involved, including Whannell’s reputation for delivering sinister magic in Upgrade and as co-writer of the original Saw, Wolfman is an obnoxiously uneven and devastatingly passionless product, resulting in a thoroughly disappointing viewing experience.

Blake Lovell (Christopher Abbott) lives with his wife Charlotte (Julia Garner) and daughter Ginger (Matilda Firth) in San Francisco, far removed from his childhood home in Oregon, where he grew up under the thumb of his controlling, militaristic father. When Blake learns that his father has been declared legally deceased after going missing some thirty years earlier, he reluctantly takes his family back to Oregon to settle his late father’s affairs, including managing the decrepit family farmhouse deep in the woods. Upon arrival, they encounter Derek (Benedict Hardie), a neighbour who offers to guide them to the property but is attacked en route by a mysterious creature lurking in the forest. This terrifying incident forces the Lovell family into isolation at the farmhouse, and things take a grim turn when Blake, scratched by the creature during the attack, begins to exhibit strange and unsettling symptoms. As Blake’s condition deteriorates, Charlotte and Ginger must confront the growing danger from both within their family and the predatory forces outside.

Every director has a misstep now and then, and I sincerely hope Wolfman is just that for Leigh Whannell. Despite my genuine admiration for his previous work, I actively despised this film. It’s not for lack of ambition; Whannell clearly had a vision here, and some elements of the film are undeniably impressive. The depiction of Blake’s transformation into the titular creature, with its heightened sensory perception and grotesque physical changes, is expertly realised through stunning production design, immersive soundscapes, and moody cinematography. These technical achievements, however, are overshadowed by the film’s unrelentingly dour tone and Whannell’s baffling decision to craft a central trio of characters so unlikeable that they border on insufferable. The oppressive atmosphere is so suffocating that the film feels devoid of any emotional or narrative release, leaving the audience stuck in an unending slog of bleakness. While Wolfman doesn’t need to be a comedy, it desperately needed moments of levity or humanity to balance its heavy-handed grimness.

To be clear, the cast does what they can with the material, but the screenplay’s deficiencies undermine their efforts. Christopher Abbott’s Blake Lovell is a largely passive protagonist, defined more by his protective instincts for his daughter than any real personality. Julia Garner’s Charlotte is similarly underwhelming, feeling like a character from an entirely different film—her emotional disconnect from both Blake and Ginger is palpable. Garner’s casting here is one of the film’s more bewildering choices, as her considerable talent seems mismatched to a role that fails to engage or develop meaningfully. Matilda Firth’s Ginger, meanwhile, is written with such a grating sense of precociousness that it’s difficult to empathise with her plight. Though it’s clear Whannell intended Charlotte to act as the audience’s emotional anchor, the lack of chemistry among the family members makes this a challenging connection to establish. By the film’s midpoint, I found myself indifferent to their survival, a fatal flaw for any horror narrative.

The film’s failure to create compelling characters might have been mitigated by strong horror elements, but even here, Wolfman falters. Whannell’s penchant for atmospheric tension is hampered by dingy cinematography and an overreliance on shadowy darkness that frequently obscures what’s happening onscreen. While an opening flashback featuring a young Blake (played with impressive conviction by Zac Chandler) and his abusive father (Sam Jaeger) delivers one of the film’s few genuinely tense moments, the rest of the runtime is plagued by a stifling aesthetic that sacrifices clarity for mood. The monster effects, though well-executed, are often undercut by frantic editing and an overuse of chaotic, frenzied camerawork that makes it difficult to appreciate the craftsmanship involved. A few jump scares and competently staged set pieces attempt to inject adrenaline into proceedings, but without a solid emotional foundation, they lack the necessary impact.

The inclusion of Benedict Hardie as Derek, the Lovell family’s enigmatic, gun-toting neighbour, hints at the potential for more sinister, Deliverance-esque thrills. However, his limited screen time and abrupt exit rob the film of an opportunity to explore a more dynamic antagonist or thematic depth. Instead, the narrative becomes a plodding exercise in mood-setting, prioritising style over substance to the detriment of audience engagement. Wolfman ultimately feels like a hollow imitation of its predecessor, trading the 1941 classic’s eerie charm and simplicity for an overwrought, self-serious approach that fails to justify its existence.

If there’s one aspect of Wolfman that truly stands out, it’s the sound design. The film’s audio mix is an astonishing technical achievement, creating an immersive sonic landscape that is as precise as it is powerful. From the guttural growls of the creature to the creaks and groans of the decaying farmhouse, every element of the soundscape is meticulously crafted to enhance the film’s atmosphere. The thunderous low-end rumbles and crisp, directional sound cues evoke the work of masters like Gary Rydstrom, lending Wolfman a visceral auditory presence that far outshines its narrative shortcomings. It’s a shame that such exceptional technical work is let down by an underwhelming story and characters.

Ultimately, Wolfman is a deeply frustrating film. Its lack of likeable or relatable characters, combined with an unrelenting tone of bleakness, renders it a largely joyless experience. Horror films can certainly succeed with morally ambiguous or unlikeable protagonists, but they must still find a way to make the audience invest in their journey. Whannell’s Wolfman fails to do so, instead delivering a plodding, uneven narrative that prioritises aesthetic over emotional resonance. While the film’s technical elements—particularly its sound design—deserve praise, they are not enough to salvage a story that feels passionless and uninspired. For fans of Universal’s monster legacy, this remake is likely to disappoint, offering little more than a grim reminder of what might have been with the studio’s aborted Dark Universe. Whannell is a talented filmmaker, but Wolfman is not a film I’ll be revisiting any time soon.