Movie Review – Silence Of The Lambs, The

Principal Cast : Jodie Foster, Anthony Hopkins, Scott Glenn, Ted Levine, Anthony Heald, Brooke Smith, Diane Baker, Kasi Lemmons, Charles Napier, Tracey Walter, Roger Corman, Ron Vawter, Danny Darst, Frankie Faison, Chris Isaak, Paul Lazar, Dan Butler, Daniel Von Bargen.

Synopsis: A young F.B.I. cadet must receive the help of an incarcerated and manipulative cannibal killer to help catch another serial killer, a madman who skins his victims.

********

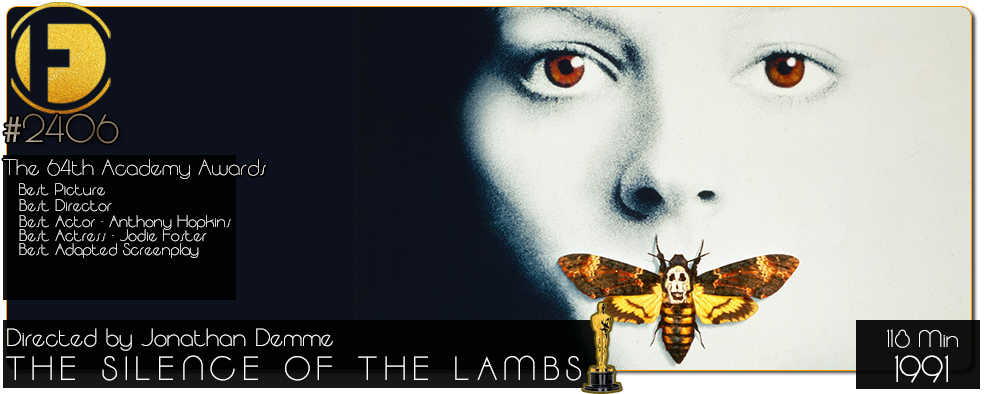

As the answer to a well known quiz night question, the legacy of Jonathan Demme’s adaptation of Thomas Harris’s novel “The Silence Of The Lambs” is forever assured; as of the writing this review, it is one of only three films to win the “Big Five” Academy Awards, snagging Best Picture, Director, Actor, Actress and Adapted Screenplay at the 1991 Oscars, cementing it as a true icon of the medium as well as propelling Anthony Hopkins, playing the sadistic and hypnotic Dr Hannibal Lecter, to superstardom. Lambs stands alongside 1934’s It Happened One Night and 1974’s One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest to achieve such a feat; given the history of this film and its effect on popular culture, reappraising it retrospectively is a mission fraught with potentially angering its ardent fanbase, and yet the question as to whether the film remains as potent and devastating as it did in the early 90’s is an intriguing one.

The story follows FBI trainee Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) as she seeks the help of Dr. Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins), an incarcerated cannibalistic serial killer, to catch another elusive murderer known as Buffalo Bill (Ted Levine). Starling’s assignment forces her into a tense psychological game with Lecter, who agrees to provide insights into Buffalo Bill’s motives in exchange for details about her own traumatic past. As their dangerous relationship unfolds, Lecter’s cryptic clues and psychological manipulation draw Starling closer to the dark truths underlying Buffalo Bill’s twisted psyche. Guided by her mentor Jack Crawford (Scott Glenn), Starling races against time to find Buffalo Bill, who has kidnapped Catherine Martin (Brooke Smith), the daughter of a prominent senator.

From its drenched misogyny, simmering horror at Hannibal Lecter’s brazen escape attempts, to the rising bile of Buffalo Bill’s capture of young Catherine Martin and her desperate attempts to escape almost certain death, The Silence Of The Lambs is one of those unique films that plays both as a stock-standard horror drama, as well as a sublime examination of sexism, class, sexuality and the nature of evil. Although the film is perhaps best remembered for Anthony Hopkins’ deserving Oscar-winning performance as Hannibal the Cannibal, with his famous line about alcohol and legumes remaining as horrifyingly off-handed as ever, now that I am able to reappraise the film from a more adult mindset it’s a staggering work of humanist subtext that shattered my expectations on my recent rewatch. I remember revisiting this film a number of times back in the early days of DVD and finding the film’s climactic double-bluff shock as compelling as ever, but it wasn’t until recently that I found appreciation in both Jodie Foster’s taciturn and magnetic performance, as well as that of Scott Glenn’s masculine paternalism, a manifestation of the film’s subtle shifting of attitudes towards women in law enforcement.

Foster’s Clarice Starling is essentially a newborn calf in the face of the FBI’s most heinous criminal system; recruited off the obstacle course to embark upon a journey into some of the most awful acts imaginable, played out with almost forensic stiffness by Demme’s hold-fast camerawork and pacing, Starling is barely given respite from the psychological torment of Lecter nor the ticking clock race to save the senator’s daughter, whose life hangs in the balance as Buffalo Bill draws out her destiny. Foster’s awkwardness and disbelief at what she encounters is marked by a steely resolve as one of the FBI’s only female agents hunts down a psychotic killer whose victims are all women – it’s a starkly obvious thing in retrospect, but at the point I saw this in cinemas (one of my earliest “you’re just old enough” screenings I can remember) I never thought much about it. Clarice’s encounters with an almost entirely male-dominated ensemble represent the gamut of misogyny and sexism present in society at that time – hell, even now I’d ascribe much of the caricatures depicted to similarly affronting creations today, nothing having changed – continues to manifest with protracted silences and knowing glances, although the final act’s bait-and-switch removal of any masculine assistance just when Starling seems to need it still tears off one’s fingernails with tension.

Foster is a supremely gifted screen talent and I found her interactions with Hopkins’ Lecter to be of particularly compelling interest, and arguably the best moments of the film. Hopkins is screen dynamite, the odious Lecter ostensibly a quietly unassuming presence whose folklore-ish legacy within the film helps the audience build up a mental backstory without the actor having to any physical activity whatsoever. When the plot demands Lecter spring into action, it becomes a brutal, devastating escape our hopelessly outwitted FBI agents are unable to counter; it would not be a spoiler to indicate that Lecter survives the film, mainly because he would reappear in both Hannibal and Red Dragon later on, but watching the famed psychologist outwit and outplay his captors, and retain his respect for Clarice’s young investigative skills, is the film’s strongest element. Although not on screen for a lot of the film, Hopkins dominates even his absences, knowing at some point he will pop out of the dark corners and surprise us all again. The Foster/Hopkins dynamic is the part of the film that resonates the most, while the Buffalo Bill subplot seems to settle into a more prosaic serial killer trope narrative. The fact that the film kickstarted an obsession with turning these psychotic serial killer types into media superstars notwithstanding, the objective supremacy of Hopkins as one of the screen’s most compelling villains remains intact.

Having said that, the exploratory aspects of sexuality and violence against women is incredibly strong here. Although the FBI profile Buffalo Bill as a transgender man, Lecter describe him as “a pretend transvestite” in a seemingly offhanded comment, as if to belittle the ideology of the trans community – on-screen, Levin’s Buffalo Bill seems to want to be female, at one point tucking his genitals between his legs to portray himself in the feminine style, which directly contrasts against his abhorrent acts against the women he kills. I’m uncomfortable with this aspect of the film’s subtext, in that Buffalo Bill’s treatment of women as some kind of reverse anger about wanting to be a woman seems counter to everything I know about transvestitism, and I’m hardly in a position to offer an explanation of this in a modern context, but it does make for an interesting subtextual statement. Ted Levine’s performance is creepy and effective, while his “victim”, poor Brooke Smith (better known to modern audiences from her starring role on long-running medical drama Grey’s Anatomy) has little to do other than scream and wail at her captivity.

In terms of its pure technical achievement, The Silence Of The Lambs is a powerhouse of directorial flourishes, cinematographical excellence and some remarkable editorial work. The film has no action sequences to speak of, other than Lecter’s escape attempt in the film’s middle act, and a lot of the film is exposition and an analytical information dump, it never feels like it slows down. From the moment Clarice arrives at the facility imprisoning Lecter early in the film, and runs across the foul Doctor Chilton (Anthony Heald), through to her staggering around in the darkness of Buffalo Bill’s basement lair while he watches on with nightvision goggles, the tension of the film never snaps until the final frames. Every body that’s found, ever twist of Lecter’s psychological riddles, every jumpscare and bump in the background, every quiet moment of introspection, Craig McKey’s editing is some of the best work I’ve ever seen. He maximises each scene’s potency and the unseen violence of the killings we’re privy to, with razor-sharp cuts and allowing the performances to play out at length, rather than cutting away. At times we don’t see the blood and gore, and at other times we’re right up in the face of its horror – although both Lecter and Buffalo Bill do some pretty horrendous things we’re told about, we actually don’t see that much for most of the film until it absolutely must be shown to maximise our terror – watching Lecter tear a guard’s face off his own head to decieve an ambulance worker is one of the grossest and most satisfying moments in horror, in my opinion. The film may have won awards for writing, but in my opinion the editing and photography is some of the strongest work the film can offer. The tone and timbre of Jonathan Demme’s direction is sublime, and whether or not you appreciate the story or the characters within it, there’s no denying the film’s style is fantastic.

A lot has been written about this film over the last several decades, and I’m too weak a writer to try and add my voice to the pantheon of those applauding the film’s effectiveness and achievements in popular culture. Several of the film’s lines of dialogue have achieved cinematic immortality – putting the lotion on its skin, for example – and Hopkins has thus far never quite escaped the shadow of perhaps his most infamous performance even to this point, making the film’s Oscar-winning successes surely the most worthy of those in recent memory. Having said that, The Silence Of The Lambs came along in a stellar four-year run of near-perfect Academy Best Picture winners, including Dances With Wolves, Unforgiven and Schindler’s List, with an argument that it might very well be the best film the 90’s would produce. In answer to my opening question: yes, The Silence Of The Lambs remains as potent and devastating all these years later. It’s a definitive masterpiece of horror, drama and thriller, a terrific combination of direction, performance and writing as satisfying as anything you’ll see made today. Deserves the awards it won – and then some.