Movie Review – Schindler’s List

Principal Cast : Liam Neeson, Ben Kingsley, Ralph Feinnes, Caroline Goodall, Jonathan Sagall, Embeth Davidz, Mark Ivanir, Beatrice Macola, Andrezj Seweryn, Jerzy Nowak, Norbert Weisser, Anna Mucha, Piotr Polk, Raimi Hueberger.

Synopsis: During World War II, a Nazi sympathizer saves the lives of hundreds of Polish Jews by employing them in his factory, all while the gas chambers of Auschwitz are firing up.

********

It’s almost hard to quantify my feelings about this film. I first saw this film when it arrived out as a new release on the old VHS brand (where is that now I wonder?) and it moved me terribly. I was visibly and emotionally shaken by the end, tears streaming down my face. A film so powerful that wasn’t a soppy, heart-string-tugging romantic comedy drama thing, no, this was film-making at it’s highest level. It’s hard to read anything about this film without the words “magnificent”, “towering achievement” and “brilliant” coming to mind. I have half a mind to simply repeat those words ad-nauseum throughout this review until you get the point. Plenty of reviews have come before this one about Schindler’s List, and no doubt there will be others, and all of them will be more eloquent than I. Still, I have to give it my best shot.

For those who were born after 1945, you will not know first-hand the horrors of World War II (and I include myself in that number) and to be honest, I am thankful. The problem WWII, apart from the human toll of death, misery and suffering it inflicted upon countless millions, is that it’s so open to review and romanticism, the chest-beating heroism of the US troops straddling France and beating the Nazi’s back to Berlin, the gallant snowfield fighting of the Russian troops, the earthshaking destruction of the Blitz across London: all have, in one form or another, been the subject of countless films and television shows. For the most part, people want to reflect on the heroism of war, the struggle by one man to save his platoon from certain death kind of thing. Nobody wants to really dig deep and suck on the harrowing, evil nature of men and women doing things you’d only dream of in your nightmares.

With Schindler’s List, Steven Spielberg demonstrated a reserved, calm expose on the horrors of Nazi wartime activities, and the desperate attempts of the few in a position to save people who stood up and did something. More renowned for his adventure/action blockbusters, Spielberg’s rather personal journey into his own family’s past allowed us to humanise all sides of the conflict: in this case, the persecution of the Jewish people during the Holocaust. Graphic, stark and unrelenting, this is film-making at its peak. Taking several stories and interweaving them around the one man, Oskar Schindler, who saved 1000 Jews during the course of the war, leaves a powerful and lasting impression of how class and wealth stood for nothing during this period.

Oskar Schindler was an German industrialist businessman, a war profiteer who turned his factory into a kind of slave labour camp for Jews and Polish residents who were being persecuted by the Nazis. The trouble for Oskar was, his factory never actually made anything that could be used, and was merely a front for the employment of these “lower class citizens” in order to protect them. Roundly praised later in life for his actions, Oskar Schindler is portrayed in this film by Liam Neeson, in what I would describe as his most perfect performance. Schindler is a hard man, a man who usually gets what he wants and flashes his money about to obtain it. His chemistry with Sir Ben Kingsley, who portrays the reliably prescient accountant Itzhak Stern, one of Schindler’s Jewish recruits, is palpable and well played. Neeson and Kingsley are superb on screen together, their performances a tour-de-force within the film, and while Neeson comes out the victor, it’s Kinglsey who serves as the rock in the cast: his nervous, twitchy accountant is the film’s resident every-man character. He’s us.

If Schindler is the very soul of benevolence in this film, then the antithesis of that is Ralph Fiennes, in his best role as malevolent SS Officer Amon Goeth. Goeth is simply an animal, a man bereft of feelings and emotions as he wallows in the slaughter of countless millions, and Fiennes manages to capture something of the insanity of the man, who kills without remorse and little empathy. It’s a stunning move by Spielberg to let us get into the mind of the “enemy”, but, after all, the Nazis were just human like the rest of us, so why not? Still, there’s something about Goeth that beggars belief; that anybody could be so callous and cruel without feeling something is extraordinary, yet this character is rooted in real life experiences, so I guess there’s something in it for all of us. Fiennes deserved an Oscar for his role here, his icy stare and childlike stammering for affection and understanding from Schindler during a critical moment is the films showpiece for me.

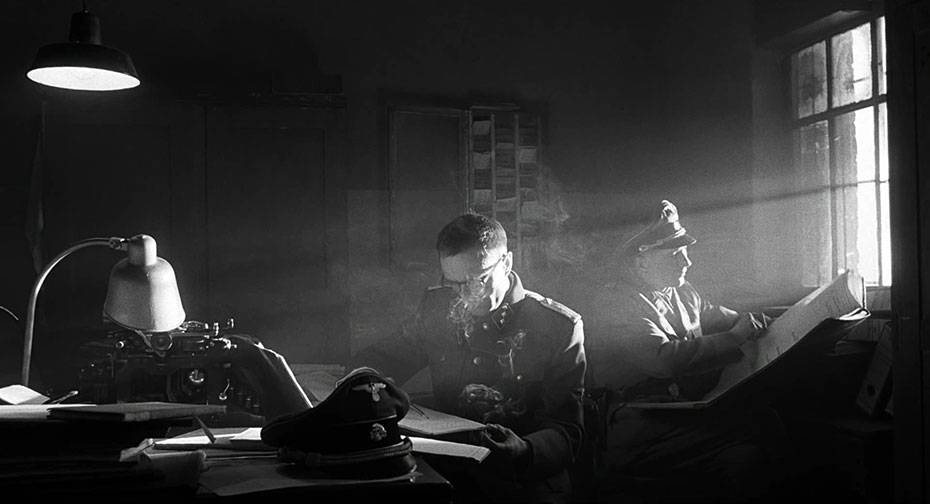

While Goeth seeks to rid the world of it’s undesirables, Schindler seeks to save as many as he can, realising that his allegiances with the Nazi party are going to come back to haunt him in the long term. He can foresee a time when the war will be over, and people like him will be seen as the enemy. The film portrays the war in stark black and white cinematography, which Spielberg utilised base don the notion that most of us have grown up seeing the war in old B&W footage over the years, and it’s the way we know of the horror that went on. An increasingly small number of us were actually there, and i think its right of Spielberg to film things this way. The use of colour on the girl in the red dress, symbolising hope dashed aside and the blood of the victims, is heart-wrenching.

Truth be told, this film is heart-wrenching all the way through. The opening moments, the closing montage of the actual survivors placing pebbles on Schindlers’ grave, the concentration camps, the liquidation of the Krakow ghetto: all are portrayed as realistically and humanly as possible. It was a wake-up call for audiences, especially those who had grown up on the butch-masculinity of John Wayne and his friends saving the day with a swagger and a grin. Here was war portrayed as realistically as we’d ever seen it, blood, viscera and gore are not shied away from here. The moment Goeth shoots a Jewish architect who gives him some bad news is forever etched in my memory as a defining moment in film.

How does Schindler’s List stand the test of time, however? In the intervening years we’ve seen films like Black Hawk Down, Saving Private Ryan, The Thin Red Line and others all vying to make war seem like hell. At least, in a way different from Oliver Stone’s Platoon and Edward Zwick’s American Civil War in Glory. All have been revolutionary in defining different battles, different political agendas and the monstrosity of man’s ability to dehumanise himself for the motive of war.

Spielberg won his first Academy Award for this film, which was vindication that he was capable of making a film that made people think, and that told a dramatic story without resorting to using Whoopi Goldberg. Whereas before Spielberg was simply a man who made blockbusters (and indeed, his other film in 1993 was Jurassic Park, which went on to become the then-highest grossing film of all time) and Hollywood owed him nothing for that; now he was a man with one of those little golden statues in his hand, a lifelong dream finally fulfilled. There was never a more deserving moment in cinema history, I think, than when Spielberg won that Oscar.

If I had to boil it all down into a single, simple summary, it would probably be this: Schindler’s List is the finest example of an anti-war film ever made, and deserves both your time and respect in viewing it. This film should be required viewing for the warmongering political powers on this earth, and is one of the defining moments in cinema when the landscape of cinema forever shifted in what was, and still is, an amazing film.

Couple things. First, the 'liquidation of the ghetto' scene in Schindler's List was of the Kraków Ghetto, not the Warsaw Ghetto. The Warsaw Ghetto was liquidated in The Pianist. Second, Edward Zwick's Glory is about the Civil War, not the Revolutionary War. I am hoping that you were using a play on words there and aren't that ignorant of history.

Review amended accordingly.