Movie Review – Lord Of The Rings, The: The Two Towers

Principal Cast : Elijah Wood, Ian McKellan, Viggo Mortensen, Sean Astin, Liv Tyler, Cate Blanchett, John Rhys-Davies, Bernard Hill, Christopher Lee, Billy Boyd, Dominic Monaghan, Orlando Bloom, Hugo Weaving, Miranda Otto, David Wenham, Brad Dourif, Karl Urban, Sean Bean, Andy Serkis, Craig Parker, John Leigh, Bruce Hopkins, John Bach.

Synopsis: While Frodo and Sam edge closer to Mordor with the help of the shifty Gollum, the divided fellowship makes a stand against Sauron’s new ally, Saruman, and his hordes of Isengard.

*****

Cinema history is littered with the carcasses of film sequels which never managed to live up to the hype and quality of it’s ancestor. Jaws 2, for example. The Lost World, the less-stellar sequel to box office giant Jurassic Park, had crashed in the public favour, even though it had made back it’s money. Back To The Future Part II was less well liked than the original, although, luckily, Bob Zemeckis struck gold again with the second sequel of that successful trilogy. The big guns had often found the creative well drying up and seeming a little dustier after the glory of the initial success had passed. Even the Wachowski Brothers suffered a massive fan backlash for their Matrix follow-ups.

Mind you, there are the sequels that do live up to, and occasionally surpass, the quality and brilliance of the films that spawned them. Perhaps the most celebrated sequel of all time, Terminator 2, became a revolutionary film in itself (like the original film, developing and showcasing new film techniques and technologies) as well as a critical and commercial success. Aliens, the James Cameron sequel to Ridley Scott’s epochal Alien, is touted as the superior film of the series. The second Star Wars film to be made, Empire Strikes Back, is often regarded as the best film of the entire Star Wars franchise.

So what makes a successful sequel? Film historians and studio executives all want the answer to that magic question; after all, if you can replicate the success of the first film in the second, you’ll stand to make more money, right? Right. And who wants more money? Everybody, apparently. People through the ages have often argued about what makes a follow-up film more or less successful than the originator. Sequels that aren’t considered as worthy are often critiqued as having weaker storylines, or perhaps a rehashing of old material, or even a lack of character development from the first film. There’s the lack of returning original cast members, which, I will admit, often turns me off sequels for the simple fact that if the original cast couldn’t be bothered, why should we? A quickly made, low-budget sequel often spells quick cash, but turgid film-making for a studio to quickly get themselves out of a financial hole. Disney, for example, have been whoring their reputation for years with their direct-to-video sequels of far superior original films. Peter Pan II: Return to Neverland? Aladdin was great, but the second and third sequel was utter rubbish. Trading on the name of an idea for the simple modus operandi of creating quick cash-flow has seen their status as a studio of quality falter and fade over the last decade. Simply put, it’s always good to work on the theory that just because you can, doesn’t mean you should. But perhaps the most common theory as to why a good sequel is good, is the fact that you take established characters and put them into a situation that’s far outside our previous experience of them. Make things darker, more desperate, more heroic, more emotional for the viewer. Spider-Man 2 uppped the ante in this regard, as did the exceptional The Dark Knight, which blew Batman Begins out the water in terms of taking an established character and putting him/her through the wringer.

For the light to shine brightest, we need to emerge from the darkness. So, take your film, put your audience through some dark times, and in the end, when you step cinematically out into the light, the audience has been on a journey that’s far superior than the original.

It would have been an impossible task for Peter Jackson to recreate the magic of Fellowship had all three Lord Of The Rings films been filmed separately, over several more years. Filming them together was a masterstroke that ensured a continuity of characters, a solid, overarching story that could be more easily planned and executed with the same cast and crew, rather than a changing roster more likely had the films been made independently of each other. The nuances and genius that had been created in Fellowship was always going to transfer to The Two Towers, and of course, come full circle in The Return Of The King.

It’s Always Darkest Before The Dawn

Released in December of 2002, The Two Towers had one almighty problem to overcome, the least of which was would it be successful? Could Jackson carry off a story that had begun in a previous film, and would only end a year later in the third act? Narratively, continuing sequels are notoriously difficult to structure, since they rarely have a definite ending, or even a definite beginning, since both those storytelling aspects of a film are not involved this time.

At the end of Fellowship, Boromir has been slain, and Frodo and Sam have departed to continue the quest to destroy the Ring alone. Merry and Pippin have been captured by Orcs, and Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli doggedly pursue them across the Middle Earth landscape in a rescue attempt. We already know the characters, so we don’t need to be reintroduced to them again. There’s an extra ten minutes of cinema we can put to good use elsewhere. So how do you start a film with no major action scenes at the start? Simple: you put one there. Flashing back slightly to Gandalf’s heroic tete-a-tete with the Balrog, and his untimely demise, we follow the path of the fallen wizard rather than the Fellowship, to find Gandalf battled the monstrous form of flame and shadow down into the underbelly of the Mountain, an almost apocalyptic battle between titans of magic and otherworldly power. With a crash, we are instantly transported mentally back to the world of Middle Earth, and it feels somewhat like slipping into a comfortable pair of shoes, or a nice warm bed. This feels familiar, and we have less set-up and more narrative development ahead of us. We cut to Frodo and Sam, scrambling across the mountainous cragginess of some far flung land, tracked by the mysterious and smelly Gollum. Frodo, aware of their tracker, manages to surprise an attack of Gollum’s to steal the Ring, and they take the wretched, tragic figure hostage, if only to lead them to their final destination upon the slopes of the mountain of fire.

We’ll discuss the influence of Gollum in more detail shortly, but for now, let us say that Jackson’s Gollum has become one of cinema’s greatest proponents of CGI/Live Action technology, and the current benchmark for filmmakers ever since. The character was always a folorn, tragic and somewhat sympathetic creation of Tolkien, perhaps representative of the powerlessness most of us feel when things are happening that are greater than we can control. Here, played wonderfully by Andy Serkis (who, I will state here and now, deserved an Oscar for his efforts) Gollum is, at first, an evil little beast who torments and tantalises both Frodo and Sam with his whining, bitter simpering. As an audience, this is great manipulation from Jackson, as eventually, we come to feel sorry for him, almost analogous of Frodo’s same sense of ownership of the creature.

Aragorn, Gimli and Legolas, perhaps, have the least to do in The Two Towers opening stanza, as they simply get to run across awesome New Zealand landscapes and pretend to follow a horde of Orcs returning Merry & Pipping to Saurman. Sauraman believes that one of them has the Ring (which they don’t) and Merry and Pippin decide to make a break for it as soon as they can, which happens after a group of Men attack the Orcs, and our two comedy-double Hobbit’s flee among the confusion. Problem is, they flee into one of Tolkien’s most fearsome forests, Fangorn. There, they meet Treebeard, an enormous living tree, who takes them to his home and then to some kind of meeting in order to discuss the next move. Treebeard, voiced by Gimli actor John Rhys-Davies, is yet another technical marvel of digital and live-action storytelling employed by Jackson, with the voice of Rhys-Davies adding the requisite gravitas to the character.

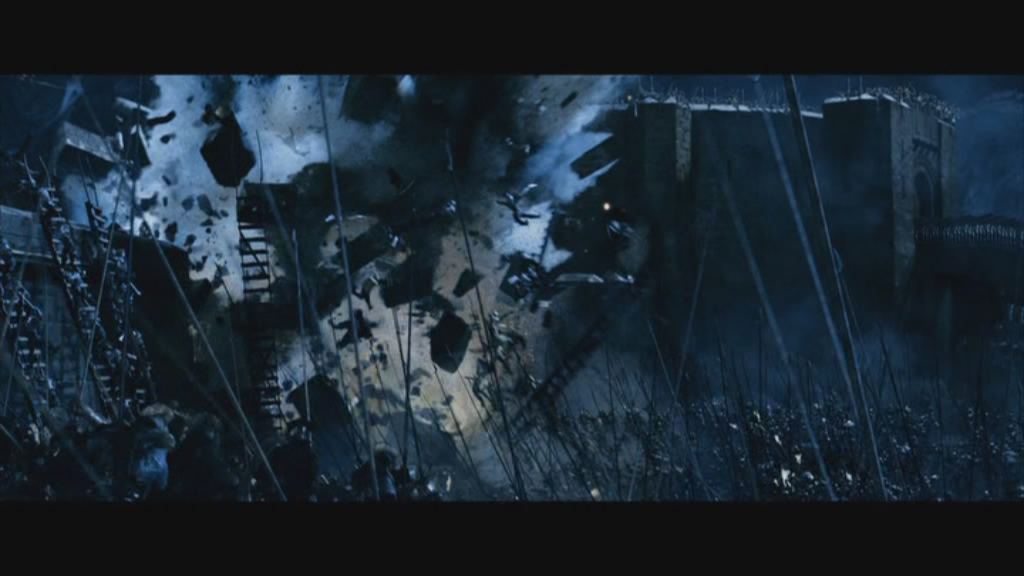

Arguably, however, alongside the marvel that is the creation of Gollum, the battle of Helm’s Deep is the film’s show-piece. Aragorn, Gimli and Legolas team up with the King of Rohan, Theoden, and his soldiers as Saruman unleashes his monstrous Orc army to slaughter them all. Theoden takes his people to their last stronghold, a bastion of rock and steel called Helm’s Deep, set back against the steep mountain wall and a fortress that has never been penetrated. With an army of 50,000 at his disposal, Saruman (a superb Christopher Lee, in the role he was born to play) does a Russel Crowe and “unleashes hell” upon Helms Deep, and what follows can only be described as one of the most unrelenting, epic, widescreen battles ever to grace the cine a screen since epic, widescreen battles were first invented. At least, that’s the way it would stay until the release of Return Of The King a year later.

The Two Towers does not attempt to dwell on events of the previous film, nor does it seek to overtly set up events in film three: Jackson and editor Michael Horton have constructed a film that is simple in it’s narrative style, and encompassing in ensuring the flavor and magic of Tolkeins’ world get to the screen like they did in film 1. There’s no overt “look what’s coming soon” material seeking to get the audience worked up over what may or may not appear in Return, the story simply tells the story of The Two Towers, unremarkably restrained by having to condense such an enormous amount of information into a palatable film for a modern cinema audience. Intercutting between the three separate storylines, Jackson weaves a tale of increasing desperation, unfettered darkness and sublime hope throughout; all the components of a good sequel.

The Two Towers is not without its problems, however. Narratively, the film is less cohesive than it’s immediate predecessor, something I think is inherited from the fact that the story branches off into separate arcs, the Frodo/Sam one, the Merry/Pippin one, and the Aragorn/Gimli/Legolas/Helm’s Deep one. Unfortunately, the one arc I found to perhaps be the weakest of the three is the last one, with Aragorn and his mates seemingly running across Middle Earth for an eternity, although things picked up with the Helm’s Deep sequence. Frodo and Sam, alone and struggling to survive both the harsh surroundings and enemies scattered everywhere, as well as the slimy, evil stench of subversion brought about by Gollum, are given the best of the film’s narrative focus, and rightly so, with Frodo’s quest ultimately the deciding factor in whether Sauron gets’ to come down from his tower. Merry & Pippin, it must be said, offer little dramatic impetus to the film as a whole, and Treebeard will be viewed as either a genuinely interesting character with implications to the story (which he doesn’t, really. The character is effectively written out of Return Of The King and he has little impact on the overall quest) or simply a muse of Tolkiens given much more free reign within the story that he deserved. If I was to be ultra-critical and realistic, Treebeard as a character serves no real purpose to the story of The Lord Of The Rings. Yes, I agree that he’s critical to the success of the defeat of Saruman in The Two Towers, but after that he kind of disappears and returns to his forest, his rage quenched in the grounds of the Tower of Orthanc, as he and his fellow Ents (for that is what Treebeard is, an Ent) take the powerbase of Saruman and smite it utterly into the water and steam of a dam unleashed. Treebeard is cool, though, in that he offers Merry & Pippin some growth in their own characters, and I guess for that, Treebeard is to be thanked. Jackson cannot be held responsible for this, though, after all, Treebeard has a significant role in the novel so you can’t just drop the character because you don’t like him or he ends up being useless. No sir, and I think Jackson and his crew did the best they could with the character.

The film dives into a pseudo-political diatribe with Theoden, for years under the thrall of Wormtongue, a meddling adviser to the King who subverts the thoughts of the monarch to do Saruman’s bidding, refusing to believe he has to fight against the Orcs: he just wants to live out the rest of his life in peace. Aragorn, who never really ever manages to be anything less than a great leader, convinces Theoden that he must fight, and after a little bit of melodramatic heave-ho-ing, the people of Rohan make a bee-line for the fortress of Helm’s Deep. Honestly, this part of the story always struck me as being a little dull. Theoden, played with commanding authority by Bernard Hill, best known to audiences as the captain of the HMAS Titanic in James Cameron’s waterlogged epic of the same name, never really explains his motivations for his actions; it’s unclear why he changes his mind like a 13 year old schoolgirl every five minutes. First, he want’s to fight, then he doesn’t, then, well, you know.

But the film’s flaws are brushed aside any time we cut back to Frodo, Sam and Gollum. It’s here the film has heart, and it’s also here we get some gut-busting character development from the three actors. Elijah Wood, whom I had seen in Fellowship as something of a weak-kneed, wide-eyed idealist, maintains that in The Two Towers, but he’s forced to confront Sam’s hatred of Gollum after his sympathy for the wretched character gets the better of him. He knows Gollum’s past, since Gandalf recounted the story to him back in the Mines of Moria and more historically over a cup of tea at Bag End. Sam, does not. Perhaps Frodo should have spilled the beans to Sam to save us all the trouble, however, Frodo’s innate good nature is the only thing keeping Gollum alive.

Sean Astin, who goes a long way in terms of character building here, makes Sam a truly torn, angry character. He can see Gollum’s mischief for what it is, a ploy to tear his relationship with Frodo apart, however Frodo can’t see it. Astin gives a wonderfully layered, searing portrayal of the real hero of the story, Samwise Gamgee, who must go places not even Frodo cannot: so deep within his soul does Astin draw out the character of Sam that it will be hard to see anybody else ever portray the role. For his performance here and in The Return Of The King, I think Astin deserved more recognition from the Academy than he got. Short thrift indeed.

However, you simply cannot mention The Two Towers, or even The Lord Of The Rings itself, for that matter, without exhorting the praises of the genius of Andy Serkis and the magicians at WETA Digital, who, combined with some state of the art effects, to produce one of the enduring icons of the trilogy, Gollum. Serkis, a British actor originally hired to perform the voice of Gollum only, with the character being entirely CGI. However, after seeing Serkis perform the role, a decision was made to supplement Serkis’ live-action performance with some of the most amazing CGI ever seen on the screen to that point. Filming of The Two Towers and Return Of The King was lengthened for the sequences with Gollum, as Jackson had to film the same sequence more than once: Serkis would perform a a take in frame with Elijah Wood and Sean Astin, and then Astin and Wood would do a retake without him. This would then be combined, edited and enhanced with the digital version of the Gollum character. The digital version was captured into the computer using the now-recognised Motion Capture technique, in which an actor is connected to a computer system via hundreds of tiny reflective dots on a skin-tight suit, enabling real-time capturing of his performance later on a soundstage.

Many people would have rightly been concerned that such a feat of digital trickery was almost certainly going to fail: they need not have worried. Jackson, confident that Serkis’ performance and WETA’s ability to render out such a complex character would surpass audience expectation, ensured that Gollum appeared on screen as much a possible, often in extreme closeup with much more detail ever afforded to fellow digital creations like Jar Jar Binks and Dobby. Gollum’s initial attack, where Frodo has his pinned down and a sword to his throat, is so real you could be forgiven for thinking for a moment that Gollum is actually there: he’s not, of course, but it’s a staggering testament to the quality of work from WETA that we think this.

Gollum is the linchpin to this film, the reason Frodo and Sam come into conflict with each other about the creature’s fate. Gollum’s fascination and obsession with the Ring begins to become Frodos, the pull of the One Ring becoming more than Frodo can bear, which allows Gollum to tempt him to give it up. Gollum, a splintered mind so wonderfully portrayed by Serkis, is given a key scene where he essentially talks to himself, or his past self, in Smeagol. Smeagol is what Golum used to be known as when he was a Hobbit; a plot point Jackson initially skirts around a little, but is elaborated upon more clearly here and in Return. Gollum is not only a fully realised digital creation, supported by a wonderful acting performance, but is a fully realised character in his own right, with a personality, a story-arc and a defined set of realistic and morally bankrupt ethics. Gollum, as I mentioned earlier, is, to my mind, representative of our own struggle against corrupting power. It’s this story point that I think Jackson hammers home perhaps a little too fervently; in essence, I think Gollum’s overpowering presence in the film takes away from the conflict between Sam and Frodo to a certain degree, although I know I am probably in a minority in this regard.

Still, the trio of Frodo, Sam and Gollum create a triumvirate of torment and anguish, a gradual darkening of the tone and narrative structure of the film as they journey their way through hell and brimstone towards the final outcome: Mount Doom.

Battles and To Be Continued

Indeed, is there’s one thing that differentiates The Two Towers from Fellowship, and even Return Of The King, is that this film is perhaps the darkest tonally of all three. Things go to crap here: Helm’s Deep results in carnage aplenty, both for the Good Guys and the Bad Guys, and the world of Middle Earth begins to rattle with the armies of war, brewing in both Mordor and the surrounds of Saruman’s tower. There’s almost no letup from the death and destruction, Saruman completely dominating proceedings here (even if only as a puppet-master, rather than definitively coming down from his penthouse suite and laying waste to things himself….. yuppie!) and the sense of foreboding hanging over the film is palpable.

Of course, Jackson has littered the film with images of hope inside this darkening feeling. Gandalf, long thought destroyed at the hands of the Balrog, returns in one simple, mysterious scene. Long derided by critics for revealing this plot development in the trailer for the movie (and thus, removing the twist in Gandalf’s return from those unfamiliar with the novels) Jackson invokes some plot reshaping of his own in order to make this film come together more thematically, and narratively.

In the same way he tweaked Fellowship from the original source material, by changing lines and doing things slightly differently than Tolkien’s texts, Jackson again stirred the plot by having things happen in The Two Towers film that were not in the original novel. What Jackson maintained, however, overriding the requirement to stay true to plot points in the novel, was the spirit of the story instead. He refused to be bound by the constrictions of the novel, and instead restructured material to suit the narrative he was trying to tell. The Two Towers is a story of hope in adversity, of standing tall when all hope seems lost. It’s simultaneously a story of broad, sweeping scope and power with the full might of Saruman’s armies being unleashed upon the world of Men and Elves, as well a more intimate, emotional journey by two Hobbits and a thing that used to be one. Plus, it’s a broadening of our understanding of Merry and Pippin, who wouldn’t get a real chance to shine until Return of The King.

Perhaps a minor point of contention, if I could make another one, is the use of Legolas and Gimli for comic relief. As the story gets darker and darker tonally, these two characters become more and more relied upon for moments of levity: I would have agreed with this as being a worthwhile idea initially, after all, there’s no laughs to be had anywhere else in the film. However, upon reflection and careful consideration, I agree with a multitude that Gimli and Legolas were treated badly by Jackson in both this film and to a lesser extent in Return. Legolas and Gimli are seen in competition with each other to have a higher body count than the other by the end of each major battle. This lampooning of both races’ seemingly indestructible mythos is at odd’s with the careful setup that came in the first film. Gimli had the potential to be a slight comedic character, albeit were it to be more subtle than displayed here: when both of them get a chance, Jackson seems to milk it for all it’s worth, until it becomes slightly corny and unnecessary. Both characters go from relatively sensible, serious folks into Bruce Willis-styled gung-ho killers with no qualms. While this might have been possible from Gimli, for Legolas it seems a little far-fetched.

However, the film’s main action set-piece, the protracted and violent battle for Helm’s Deep, is worthy of special mention. As if the audience didn’t have enough to look at in the Gollum character, they also had one of the great battles of cinema to get through as well. Wet, violent and not without it’s share of heroism and victims, Helm’s Deep is a massively structured, and shot, battle between thousands of advancing Orcs, and a couple hundred Men and Elves. This sequence is enormous, the scale beyond mere description here: the walls of the fortress thunder with the power of the forces Saruman throws at humanity, the arrows piercing the sky, the gunpowder devastating our heroes’ chances of survival, until a spine tingling moment when Gimli signals the arrival of the King of Rohan, and a desperate “last stand” is enacted by Theoden and his soldiers. Helms Deep is a pivotal moment in the story, as it set’s the scales of balance a little further in favour of the forces of Good. Until then, we hadn’t really seen a lot of truly menacing fighting from either side, although glimpsed somewhat in Fellowship, we’d no idea just how awesome this was going to get. Our heroes’ seemingly infallible belief that they could possibly win seemed unfounded, and indeed, Jackson play’s this up in the narrative as he constantly reminds us of just how massive and awesome the army of Saruman, and to a lesser extent in Towers, Sauron, actually are. Theoretically, there’s no hope for Theoden and his friends, the Elves and other fighters in the battle. It’s merely a case of how long can we hold out, rather than how long will it take for us to kill them all. As the Good Guys look out over the time-worn battlements, upon the advancing horde of malice and evil, they must know within themselves that no matter what happens, there’s truly no hope against such numbers. It’s such despair that provokes the square-jawed last stand of Theoden, provoked into action by the call of the enormous horn running the height of the enormous tower, which reverberates around the Deep and inspires the remnants of the defending force to battle.You can feel the glimmer of futility within each of the characters, the sense of a battle lost, as they rampart down the long entrance slope of the Deep, through oncoming Orcs, towards their almost-certain fate….. death. Suddenly, the arrival of Gandalf, garbed in ethereal white and followed by “the cavalry” of Rohirrim, gathered from across the land in the hope of defeating Saruman’s army, elicits the thrill of victory in our heroes’ faces, the justifiable magnificence of Gandalf’s charge of rescue espousing the hope we should all have against incredible odds.

I mentioned earlier that the second film of a trilogy is usually lacking in a quality ending, although I think in this instance, Jackson has succeeded in concluding The Two Towers at a natural point. The end of the battle with Helms Deep, with Gandalf, Theoden and Aragorn looking out across the Middle Earth landscape, is perhaps the perfect opportunity for an audience to take a breath after the carnage and destruction of Helm’s Deep. The film has, by this stage, perfectly set the story up to be concluded in Return Of The King: Gandalf’s statement about the battle for Middle Earth only just beginning, lets the audience know that if you thought Helm’s Deep was big, you had to see what was coming next. Frodo and Sam, as well as a deplorably malcontent Gollum, survive their capture by Boromir’s brother, Faramir, (David Wenham, who, I think, is criminally underdone here… perhaps it’s just the editing, as his role is significantly beefed up in Return) and are released on their way to destroy the Ring.

The audience, after being taken on a rollercoaster ride through three hours of The Two Towers, knows that the best is yet to come: Frodo and Sam are nowhere near Mordor, after all that time; Saruman is defeated but Sauron still remains, and Gollums’ plan to lead Sam & Frodo to “her” indicates that there’s still along way to go before this story is over.

Jackson’s moulding of the narrative is masterful, and while perhaps not a decidedly faithful retelling of Tolkeins novel, intrinsically it’s tonally identical, and in keeping with the spirit of the story as begun in Fellowship. The director has asked a lot from his cast, crew, and the audience: he gives us staggeringly complex effects shots and storytelling techniques, most of which would be major shots in any other film, and treats them almost as if they are merely nothing, and he asks the audience to brave the looming shadow of Mount Doom to follow his characters on journeys that are filled with danger and intrigue for 3+ hours of film time. It’s a film that was never going to truly satisfy the traditional film critic, who would perceive the lack of solid beginning and end as lazy filmmaking: Jackson was forced into a directorial corner to be a little more inventive, and I think the way he opens and closes the film is spot on.

Whether you agree with my comments of not, Jackson surely must take some praise with him for keeping The Two Towers tonally and structurally similar to the preceding film, even as he takes the characters in directions that lead to darker, more emotionally draining stories. He has brought Tolkien into the mainstream, and while purists can argue the nitpicking until the cows come home, I feel that The Two Towers is the perfect second film in the trilogy, as it reminds up of just what is at stake throughout the story, and takes our heroes into uncharted territory. It handles the lack of cohesive narrative structure well, by intercutting all the stories reasonably well, allowing the development of tension and drama to play out more naturally and with less reliance on “I wonder what’s happening to x & y over in the other area” dialogue so prevalent with lesser films.

The Two Towers is a staggering achievement in both cinematic style and storytelling. Audiences around the world breathed a sigh of relief that the second film of the trilogy was on par with the first. Only time would tell if Jackson and Co could hope to pull off one of the worlds greatest cinematic triumphs. It would take a year to find out.