Movie Review – Life Of Emile Zola, The

Principal Cast : Paul Muni, Gloria Holden, Gale Sondergaard, Joseph Schildkraut, Donald Crisp, Erin O’Brien-Moore, John Litel, Henry O’Neill, Morris Carnovsky, Louis Calhern, Ralph Morgan, Robert Barrat, Vladimir Sokoloff, Grant Mitchell, Harry Davenport, Robert Warwick, Charles Richman, Gilbert Emery, Walter Kingsford.

Synopsis: The biopic of the famous French writer and his involvement in fighting the injustice of the Dreyfus Affair.

********

The Life Of Emile Zola is exactly the kind of film the Academy loves to award Oscars to. Profoundly dramatic, searing with the heat of true events and a wonderful cast in scintillating form, and devoid of apparent melodramatics, Zola’s Best Picture win is both just and sure, riveting from start to finish and led by a compelling Paul Muni in the title role. Although one could suggest the film’s focus on the Dreyfus Affair should have meant a more appropriate title, Zola’s machinations and his agitation of high ranking political and nationalism are dealt with in the most uplifting and Hollywood way possible.

Lowly poet, novelist and agitator Emile Zola (Paul Muni) becomes wealthy following the publication of a seemingly salacious novel, Nana, in the mid-1800’s, and spends his years continuing to provoke controversy with his many future books. Living a life of contentment, Zola is dragged into the affairs of a wrongly convicted French military officer, Alfred Dreyfus (Joseph Schildkraut), who is accused of supplying intelligence to German officials, based upon a flimsy suite of evidence. The real perpetrator, Esterhazy (Robert Barrat), is found to be guilty to the crime but is officially acquitted so the military, corrupt and rotten, can save face. Dreyfus’ wife, Lucie (Gale Sondergaard) exhorts Zola to take up her husband’s case, inciting action from those in power who do not wish the truth to come out. Accused of libel, Zola himself faces lengthy prison time.

If this film proves one thing, it’s that French courts in the 1890’s were absolute bullshit. The Dreyfus affair was by all accounts incredibly divisive in France in the day, a protracted and hostile legal battle to clear an innocent man’s name dragged Zola into the courtroom and sullied his good name. Passionately French, The Life Of Emile Zola takes a crystallising historical moment and transforms it into a powerful patriotic klaxon against corruption and a fascinating look at Hollywood’s early fascination with historical events as a method of entertainment. Zola was written by Heinz Herald, Geza Herczeg and Norman Raine, and is as portentous as it is enthusiastic for its subject matter. It brushes over Zola’s early years, touching on his success with Nana before skipping ahead to his later life, in which he writes at his stately home and barely becomes involved in “causes”. A large portion of the film is spent setting up Dreyfus’ initial accusation and Zola’s eventual representation of him to the French Court, while bookending with dialogues of peace and acceptance, a sense of righteousness and the optimism of human existence that is in most respects quite stirring. It’s a well written screenplay, containing plenty of barrel-chested speeches and stirring monologues that are obviously pointed towards Oscar favouritism; echoes of this film are found in almost any film dissecting war and corruption, notably Chaplin’s The Great Dictator a few years later, and the film is eminently quotable in this regard.

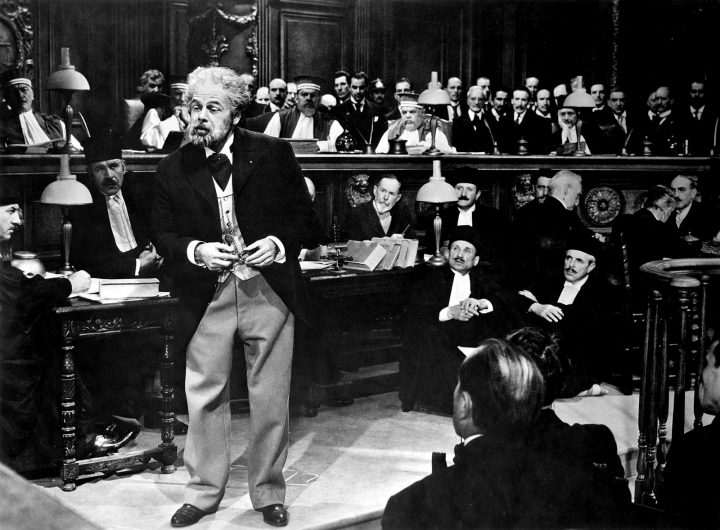

Zola’s chief asset is the fluency of William Dieterle’s direction, while not particularly showy or technical remains solid and commanding in its ability to convey the tones and subtext of Emile’s battle for justice. The dusky streets of Paris and Europe, the stately military offices and the dank, squalid nature of French prisons are captured with a stark sense of lighting and photography, while the performances captured indicate a less staged creativity behind the camera. Lengthy court sequences in the middle section of the film are well handled and driven by a sense of unfairness (the court would constantly prevent Zola’s lawyers from cross-examining almost all the witnesses involved, nor allude in any way to the Dreyfus affair, which is bizarre considering it was the latter which provoked Zola to speak out against an unjust military system) and the background to the major players isn’t particularly deep, and I’d have liked the film to capture more of the dichotomy between those who believed in Drefus’ innocence and those who did not, but the focus on Zola himself keeps the reins on a potentially broader spectrum of plot from overriding the film’s core subject matter.

Zola’s cast deliver performances that replicate the quality of the script; Paul Muni, as Emile, is borderline harumph-harumph garrulous in his style but through sheer force of screen persona endears himself to us as a man of passion and truth, selflessness and acquiescence to his position in life. Muni’s courtroom exhortation is among the great screen speeches in cinema, whilst co-star Joseph Schildkraut’s Oscar-winning performance as Dreyfus is brief enough to baffle as to how he snagged such prestige. The supporting cast, including a slimy Robert Barrat, a solid Henry O’Neill as the investigation’s crux in Picquart, and a sublime Harry Davenport (who would go on to co-star in Gone With The Wind) as the French Chief Of Staff who throws Dreyfus under the bus in the first place, provide rock-solid work backing up the key leads.

The Life Of Zola isn’t driven by spectacle, and at its core attempts to examine a pivotal moment in French military history and briefly bring attention to one of France’s more famous literary exponents. While its story might feel passe in our modern society today, its sense of right and justice and poetic uprightness remains an idyllic Hollywood motif even now, and it’s little wonder the film snagged Best Picture against such classic contemporaries as Captain Courageous and A Star Is Born. The Life Of Zola is a dynamite story, told with passion and a contracted time frame, while its solid cast and workmanlike direction ensure it is a remarkably prescient film despite the years since its release suggesting modernity may have passed it by.