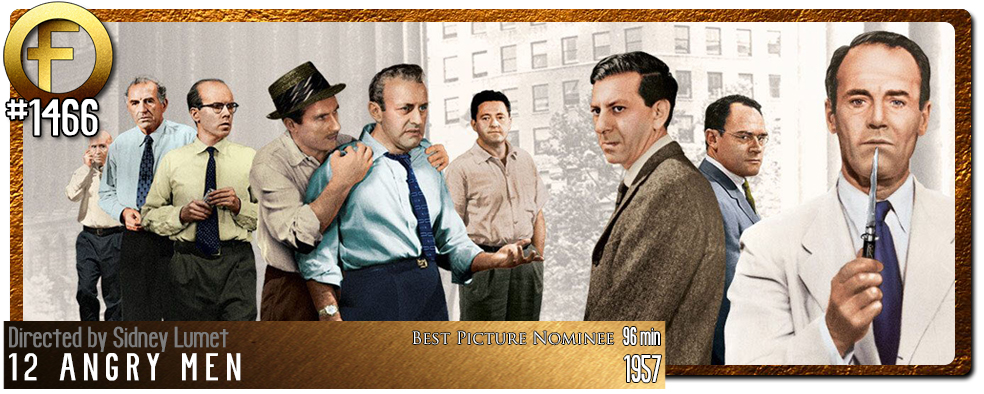

Movie Review – 12 Angry Men (1957)

Principal Cast : Henry Fonda, Lee J Cobb, Martin Balsam, EG Marshall, Jack Klugman, John Fielder, Edward Binns, Jack Warden, Joseph Sweeney, Ed Begley, George Voskovec, Robert Webber.

Synopsis: A jury holdout attempts to prevent a miscarriage of justice by forcing his colleagues to reconsider the evidence.

*****

Searing, heart-pounding, exhilarating; not words usually associated with a talky mid-50’s drama set in a jury room but 12 Angry Men is exactlythat. Featuring some riveting performances and a withering screenplay by Reginald Rose (The Porcelain Year, Black Monday), Sidney Lumet’s Best Picture nominee is a remarkably precise technical achievement and one of the great American films. The fact that it lost to Bridge On The River Kwai is testament to Kwai’s status indeed, for were I to contrast the two together, I’d likely as not choose this courthouse-based drama over the Alec Guinness war flick every time. 12 Angry Men is a brutal portrayal of racism and prejudice, of the belief in American values whilst refusing the uphold them, and of one man’s persistent questioning of testimony to truly bring justice to the screen.

A hot summer’s eve, New York City. A stifling jury room in a city courthouse sees 12 members of a jury enter, to deliberate on the fate of a boy we never meet, who has been accused of murdering his father during an argument. A unanimous guilty verdict will send the boy to the electric chair, while a hung jury will result in a retrial. 11 of the twelve men initially vote for a guilty verdict, with one, Juror 8 (Henry Fonda), casting a not guilty vote. Upon questioning him, he believes there’s enough “reasonable doubt” to not convict the boy, whilst others, including an older bigoted car dealer (Oscar-winner Ed Begley – Sweet Bird Of Youth) and violence-prone businessman (multi-Oscar nominee Lee J Cobb – The Brothers Karamazov, On The Waterfront) rail against the delay and insist they simply vote to convict. As the evening progresses, and Juror 8 begins to unravel the testimony of the case and the key witnesses presented to them, gradually more and more of his fellow jurors decide to cast a not guilty verdict. Eventually, as tempers flare and the last holdouts continue to assert their wilful ignorance or simple disdain for the process of justice, Juror 8 uses gentle reason to tear down even the strongest of arguments.

12 Angry Men was a film I watched for the first time in high school, as part of a writing assignment. Around the same time, our teachers were also showing us films such as To Kill A Mockingbird and Polanski’s Macbeth (yeah, I know, right?), and while my juvenile self felt disdain at the time for having to sit through a film where there were no explosions, I always remembered 12 Angry Men felt like a beacon call of white hope against a raging swell of despair and resentment; never has a film felt so critical to modern day dialogue than one written midway through the 20th century.

It’s a poker to the eye of facetiousness and dullard arguments about American values, ideals and beliefs, as William Holden’s iconic Juror 8 role calmly, simply expunges the bigoted, racially motivated, ignorantly constructed arguments the rest of his panellists exhibit to bring truth and justice to the accused boy’s case. Rose’s screenplay, which takes almost no time to set up before delving into the case and the juror’s individual personalities, is an onion-layered example of carefully constructed emotional rigidity; each of the jurors exhibit their own personalities which contrast against all the others – one, played by Martin Balsam, is the semi-reluctant jury foreman, whose desire to conclude what seems to be an open-and-shut case runs congruent to bully-boy Juror 3 (a fascinating acting performance by Lee J Cobb, and one worthy of an Oscar all on its own – I couldn’t take my eyes off him) who wants the same thing but achieved in a different way.

Facets of American life are represented here, from the immigrant (George Voskovec) clockmaker to the All-American baseball-loving-but-ignorant salesman (Jack Warden), to Ed Begley’s outright racist bigot representing “old America”, to William Holden’s more liberal, pacifist leaning architect, like a patchwork quilt of all things that make the United States the boilerpot it is today. Balancing the bigger names are character actors including EG Marhsall (known to some for playing the US President in Superman II) as a bespectacled stock broker who believes the boy’s guilt without the hysteria several of his fellow jurors do, and the wonderful Joseph Sweeney, as an elderly man critical of the turn “modern” American life appears to have taken, and the one who supports Holden’s Juror 8 almost all the way through.

Not a single actor in this film feels out of his depth or incapable of delivering an honest, attuned performance. From Holden down to the least of the cast, everyone has their moment to shine (so to speak) as their arguments about the boy’s guilt slide away. Rose’s screenplay applied acidic righteousness to almost all the belligerent characters here, while the more congenial or middle-ground remain rooted in believability as a muted sense of right-and-wrong. It’s a delicate balance that plays well with idealism today, the film’s focus on the boys innocence in the avalanche of evidence against him (almost all of which is either inconclusive or proven ineffective during the course of the film, if not rooted solely on prejudice to his race) a supremely nuanced and powerful indictment on belief overriding sense. As the film picks the scabs of our character’s personalities and their belief structures, so to it picks apart the viewer’s preconceived ideas about how things will transpire. We never meet the accused (glimpsing him only in a brief courtroom appearance to open the film), or the witnesses who provide testimony against him, and for only three or four minutes of the entire film are we ever outside the jury room, so our understanding of the case is derived solely from the white-hot dialogue and pulsating pacing Lumet achieves.

The film’s sense of claustrophobic pressure, the ready-to-ignite tinderbox of inbred prejudice within the titular 12 angry men (and most of them are angry about something, in some form or another) is captured perfectly by director Sidney Lumet’s hypnotic camerawork, which itself is a masterclass of technique and style that deserves far more attention today. The film begins utilising plenty of wide, high angles, allowing multiple actors so be contained within a single shot (which, I might add, adds velocity to the dialogue sequences in a manner I’m still struggling to deal with it’s so good) before eventually ratcheting down to close-up, short depth of field shots for the film’s bruising conclusion. The heat of the room, personified by the sweaty, irascible arguments within the room, and the rising bile in the more antagonistic of characters, only serves to further heighten the pressure on the viewer until you literally can’t take your eyes off them.

Lumet’s choice of shots, his editing and camera movements, are absolutely mesmerising from a technical perspective. He hits the naturalism and theatricality of the piece just right, finding the balance between showmanship – of which 12 Angry Men has oodles – and precise dramatic strength through compelling beats of silence and unsaid drama. Lumet is fortunate to have assembled such a bunch of talented actors to assist his mission, of course, but with every cutaway to another angle, every move of the camera covering multiple conversations at once or intercutting between several as the camera roves around the room, the film bristles with a hidden anger only belied within the title. In short; the film is superbly shot, and a masterclass of editorial and cinematographic prowess.

It’s a film that feels like it’s still got a lot to say even sixty years after debut. Modern America exhibits much of the uncomfortable racism and indifference to justice that the country’s founding fathers exemplified in the nation’s precious constitution, and the film’s pointed exemplar of that doesn’t go unnoticed, nor is it subtle about it. As if to suggest pathological indifference to our humanity, Begley’s bigoted old fool rails against the accused boy’s race, social standing, propensity for crime and violence, all while other members of the jury turn their backs to him. It’s the film’s less-than-subtle way of suggesting that these old beliefs and expectations are prehistoric, a ruinous thinking for a less progressive age. It’s something many countries around the globe have sought to impress on Tump’s America by way of his own stubborn white-nationalist zealotry, exhibited almost daily through confrontational umbrage about justice and nationalism, of all things.

Another element, less hopeful than the overall narrative but one that persistently remains socially expedient is the breakdown of family, represented through Cobb’s desperately estranged father figure – after trying to teach his son “how to be a man” via physical violence, his son leaves and doesn’t return. This fracturing is redolent of a greater generational breakdown, and the film’s use of this grief and impotent rage – similar to those awful parents who excommunicate their own children for revealing their homosexuality – is indicative of many ailments modern society still faces. The film doesn’t overtly point out how little we’ve changed, but our own guilt about this lack of action will strike at the heart of any viewer attuned to the film’s message of hope.

What’s most surprising is how familiar 12 Angry Men feels as an ecosystem of social anxiety and rage in contrast to the post-millennial age. The film doesn’t hold back on making clear how abhorred truth and justice in America has become, for a country which prides itself so lustily on these ideals. As Lumet’s razor-wire direction catapults us into the simmering heat of a single jury room, and the fate of a young man’s life hangs in the balance, 12 Angry Men would, should, and probably will, make you furious we’re no further socially from this film after it than we ever were before.

What an awesome film this is. To piggyback off you a bit, not only is it remarkably precise, but it’s remarkably concise as well. And that’s a tough trick for a dialogue driven film. Thanks to writing that snaps and performances that sizzle, it never overstays it’s welcome. Instead it continually draws us in. Lumet’s subtle direction helps it do that, too. Such a masterpiece.

Absolutely. I think it’s one of those films that works beautifully both with writing and performance being in such concert with the other, if one was lesser the other would support it, but both elements work superbly. Concise is perhaps the best word to use, there’s almost no part of this film that doesn’t work towards the story or characters, and that is something missing from a lot of Hollywood stuff these days!