Movie Review – Bullet Time: The Matrix Versus Equlibrium

The skies darken. The shadows loom large. The sound of apocalyptic nihilism draws people to the cinema to witness one of the mediums most profoundest seismic shifts in decades. Somehow, somewhere in the darkest corners of the Warner Bros. lot, a duo of directing brothers accomplished something modern Hollywood had, until then, seemed incapable of creating: an intelligent, multi-layered and utterly captivating action/sci-fi thriller. We were officially welcomed into the Matrix. And film would never be the same again. A few years later, unheard of director Kurt Wimmer released an almost equally unheard of Christian Bale upon cinema audiences, in a post-apocalypse sci-fi/thriller entitled “Equilibrium”, creating an equally multi-layered and intelligent film for audiences to find. However, only one of these two films did the business.

[Editors Note: This review is a modified version of that originally posted on www.moviesmackdown.com. The original review can be read in full here.]

The skies darken. The shadows loom large. The sound of apocalyptic nihilism draws people to the cinema to witness one of the mediums most profoundest seismic shifts in decades. Somehow, somewhere in the darkest corners of the Warner Bros. lot, a duo of directing brothers accomplished something modern Hollywood had, until then, seemed incapable of creating: an intelligent, multi-layered and utterly captivating action/sci-fi thriller. We were officially welcomed into the Matrix. And film would never be the same again. A few years later, unheard of director Kurt Wimmer released an almost equally unheard of Christian Bale upon cinema audiences, in a post-apocalypse sci-fi/thriller entitled Equilibrium, creating an equally multi-layered and intelligent film for audiences to find. However, only one of these two films did the business.

Current Batman incumbent Christian Bale had raised a lot of eyebrows with his stunning transformation from little-known British actor in films like The Machinist, to big time headline star of major studio blockbusters, however, most people may have missed one of his lesser known films: Equilibrium. Set in an apocalyptic future Earth, the film tells the story of John Preston, a Grammaton Cleric charged with subduing any behaviour showing emotion in the populace. It was felt that emotion was the primary factor that lead to war, and so, the government outlawed it. Anybody charged with having an emotion finds themselves at the wrong end of an incinerator, but when Preston himself starts to “feel” things himself, he quickly becomes the hunted, rather than the hunter. Equilibrium slid in and out of cinemas quite quickly, back in 2002, although many feel that it was unjustified in it’s critical panning.

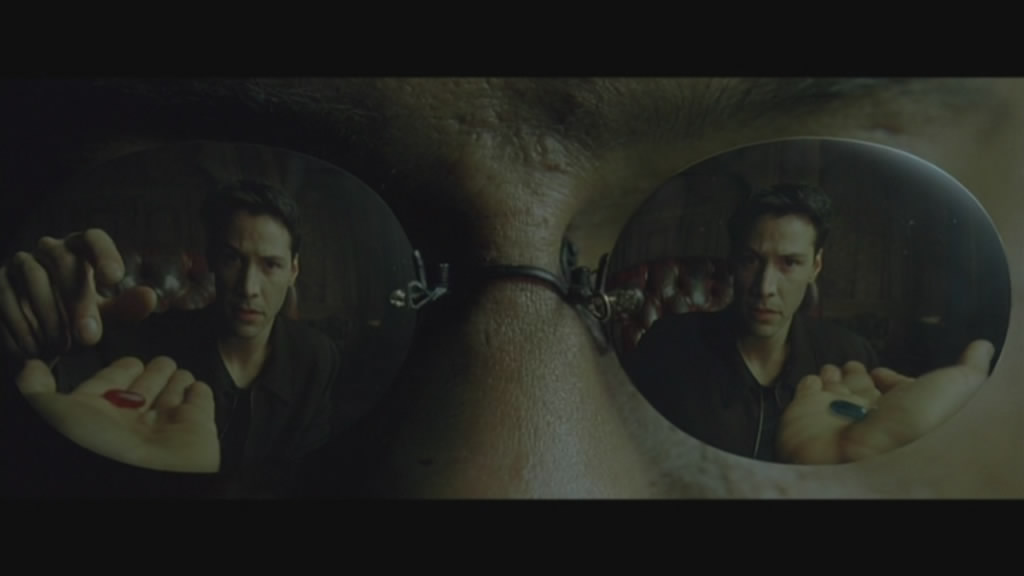

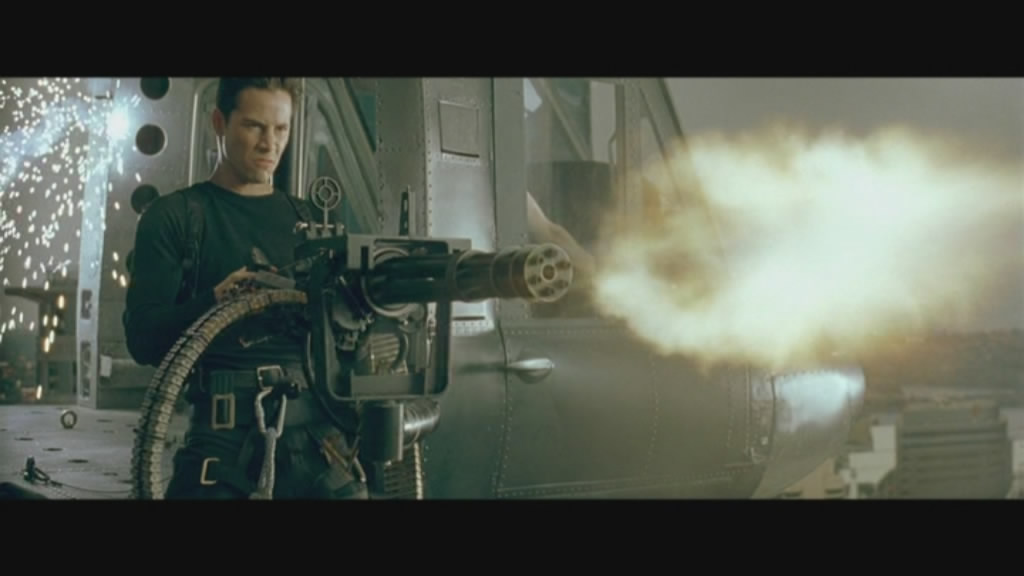

There’s very little that can be said about The Matrix that hasn’t been said before. Apparently, according to the film, reality is the wool that has been pulled over our eyes to blind us from the truth, and nobody can be told what the Matrix is, you have to see it for yourself. So says Morpheus (Lawrence Fishburne) to Neo (Keanu Reeves), before the world Neo knows is blown utterly to pieces. Humanity has been subjugated by the Machines, kept in a state of perpetual hibernation and plugged into an artificial world known as the Matrix, which, according to the Machines, keeps us dormant and happy. Humanity is “grown” for the sake of a power supply for the Machines, and upon his release (or, “awakening”) by Morpheus and his crew, Neo comes to realise that he has a special destiny. If only he can remember that there is no spoon. Filled with dynamic and spectacular stunts and special effects, The Matrix became a phenomenon, and a modern cult classic for the ages. And, it would seem, create an almost insurmountable legend for itself.

We begin with a magnificent right hook. A woman, dressed in black, stands alone in a darkened room, talking secretively on the phone. We see police approaching via the hallway, torches and weapons drawn. There’s an explosion of wood, the door bursts open, and the woman, whom we can only guess at her purpose, stands still, awaiting the moment to strike. The police movie in, handcuffs drawn, when suddenly, in a blur of sound and violence, the woman pulverises the first police officer, rounding on the rest with a gun drawn, firing almost belligerently into the men around her. Then, she does something perhaps even more remarkable. She strides up, around and onto the wall, swinging herself out of the line of return fire and devastating the lawmen. As the gunfire ceases, the woman stands alone again in the room, the bodies of the vanquished before her.

As an audience, we gasped as one. Individually, you began to get that thrill down your spine that perhaps, you were not watching simply another sci-fi action film, but indeed, something special.

Yet, the sequence was not over. The woman, running from the room, finds herself pursued across the rooftop of the building, approaching a gap between that and the next rooftop: it’s too far, you think. But no, the woman, carrying her weapons and barely breaking a sweat, leaps across the gap between the buildings, through an open window, down a flight of stairs, and ends up facing back the way she’s come with guns levelled for approaching targets.

And it’s not over yet.

The woman runs towards a phone booth, for what reason we do not know. A truck, large and industrious, lumbers into view, smoke billowing from it’s tyres and the menacing foreboding of blackened windscreen preventing us from identifying the driver. The woman pauses, regards the vehicle, which is now pointed directly at the phone booth. She sets off, hoping to beat the truck, which takes off simultaneously. As the truck lurches towards the booth, the woman enters, and unhooks the receiver. There’s a buzz, an electronic whizz, and the truck slams into the booth, obliterating it and whoever is inside.

The truck stops, a man gets out, and whispers conspiratoriously to another. We see that there is no body in the remains of the booth, and as the movie slips into a new scene, we are left wondering: where did she go, and who is she?

So begins The Matrix, the blockbuster film directed with style to burn by brothers Andy and Larry Wachowski. The Matrix, a film nobody knew about before it was released, has now become part of popular culture, it’s vocabulary is understood and copied almost verbatim by internet geeks and cinephiles the world over. The film spawned two sequels, plenty of fodder for parody, and a genuine cult following of a status accorded only Star Trek and Star Wars. The fame and adulation from critics and filmgoers the world over has been much challenged by those few who seek to tear down the film as merely a simple, sci-fi extravagance, lacking in things like characterisation, subtlety and style. However, there can be no doubting the class and style with which a cinematic legend was born.

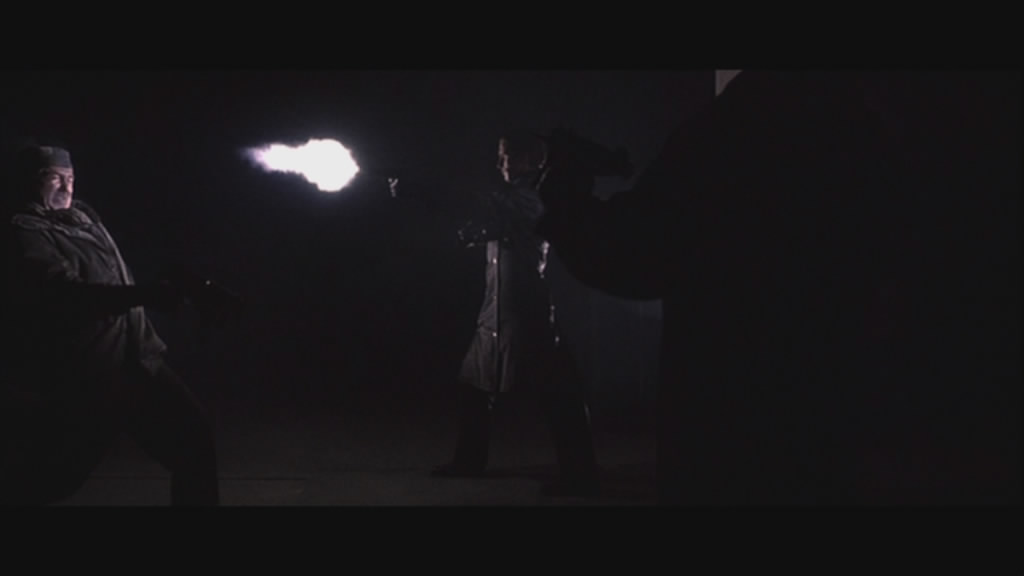

In 2002, the left hook comes along. Noses bleeding from The Matrix, we encounter John Preston (Christian Bale), Grammaton Cleric and one of the most awesome wielders of weaponry we’ve ever seen. We begin with a voice over, a few generic images of violence and battle, coupled with a narrative informing us of humanity’s desperation to avoid World War IV, which would indicate that at the time, Earth had almost been lost in a conflict so massive it beggared comprehension. A new order was created, of emotionless soldiers, tasked with destroying and removing any evidence of creativity, of love and hate, of obliterating cute, furry animals and anything that produces an emotion in a human being. Humanity is drugged up, on a substance that represses emotions. There is a Resistance, of course, to this regime, who desire a return of humanity’s soul, and are fighting a losing battle to obtain it. We meet our central character, John Preston, who, along with Cleric partner Errol Partridge (Sean Bean) arrives at a pitched battle between police, and members of the Resistance.

Preston, taking the lead, sizes up the situation. Partridge stands back, awaiting the carnage. Bullets fly, shadows dance upon the walls. He draws two massive pistols from his coat and prepares himself. In a moment, he flings himself towards a door, which has been barricading the Resistance fighters from the approaching law. Smashing through the door, Preston is engulfed in a hail of bullets, pitch darkness and the cries of frightened men. There is silence. The screen is dark, completely so. Softly, almost fearfully, we hear a voice, half whispered, wondering if “they got him”. There’s a response, on the other side of the screen, another voice filled with terror answering. Silence. More whispered voices. Silence lengthens, before eruption.

The screen explodes with light; a flash-bang rapidity of gunfire, casting a deathly pall on people frozen in time, the muzzle flash allowing us a stop-motion glimpse into the carnage the soundscape reveals all to horrifically. Preston stands, crouches, leaps and weaves, his posturing and positioning preventing himself from being struck by return fire.

Then, there is silence again, and the darkness slowly, ever so slowly, gives way to the subtle glow of the heat from Preston’s guns, the barrels red-hot. Our jaws drop to the floor, astounded by what we have seen.

Preston walks from the scene, the battle over, his job done. at least, for now. Equilibrium has begun.

The two films here today are both top class efforts of sci-fi action. Why, then, did one film fail and the other succeed, given the similarity in style, and in tone. Both The Matrix and Equilibrium have a kind of epochal, nihilistic tone, the characters garbed in black and almost exceptionally gifted with weaponry, trying desperately to return humanity to some kind of “real” structure and purpose. Whilst in The Matrix, this skill with weapons is passed off as education via computer, in Equilibrium, the Grammaton Clerics study the use of the Gun Kata, a weapons based martial art that (according to the films screenplay) allows the weapon holder to remain in a position most likely to prevent him/her to be struck by return fire.

Both feature characters seemingly devoid of any emotion: Morpheus is a prophet of sorts, calm and calculating as he coaxes a performance from Neo, to battle the film’s evil Agents, which threaten to destroy them all should they win. Neo, played without any real emotion by Keanu Reeves, is the central character who must somehow overcome his mental limitations and become the saviour of mankind. This Christ-like representation is again delivered in the form of John Preston, in Equilibrium, who must sacrifice almost his entire life to ensure the safety and stability of humanity, in a resurrection-styled narrative replete with subtextual meaning and analogous parallels.

The script in The Matrix is filled, nay, stuffed, with hidden meanings and subtextural layering, so much so that the DVD release in recent years has seen philosophers record commentary tracks to explain what’s going on. Philosophers? On a film about people trapped in a giant mental hoax? The Wachowski Brothers piled in themes and thinking from almost every religion they could, Christianity, Buddhism, Islam, heck, I’d say even a little Paganism was shoved in too, although I’d be struggling to point it out. The point is, The Matrix has been dissected and discussed almost more than any other film of the modern era, at least in terms of it’s meanings and themes.

Equilibrium is less theological than that, and instead relies more on the emotion, or lack thereof, in humanity to obtain it’s narrative thrust. The film asks us to question the very thing that produces destruction, emotion, and it’s relevance and importance to us as a species. Without love, balanced by hate, would we have a more peaceful existence? If there was nothing to love, nothing to hate, why would we fight each other? Would the removal of the thing that makes us so passionate about things engender peace, or, as suggested in the film, provoke a degeneration of us as a species to the point where our lives are more akin to robots, simpletons with no free will or free thinking.

Christian Bale, himself no stranger to films filled with the torture and dissection of humanity’s ails, is dramatic and engaging as a man struggling to exist in a world he feels increasingly isolated from. He “feels” emotion in gradual spurts, throughout the film. At first, he tries to suppress it, but then actively pursues the expansion of these feelings, gradually coming to understand that the government, led by Hitler-esq Father (Sean Bean) has gone beyond what was initially required to prevent war, and is now in the business of controlling humanity using drugs. Their reliance on Prozium, the drug developed to repress emotion in humans, is the key factor in Prestons resistance. As he uncovers the hidden truths about his Cleric order, and about Father, he begins to realise that he alone has the power to bring down the government, and return humanity to it’s former glory, since things appear to have gone too far.

It’s an unexpected meeting between Preston and a woman, Mary, played by Emily Watson, that sparks the dramatic change in Prestons outlook, convincing him to go against a lifetime’s training and learning to dig deeper, and uncover the truth.

The Matrix, however, has us digging deeper with humanity in a more literal sense, as the last of the free-thinking humans have created a city, Zion, deep underground near the Earth’s core, away from the surface and the Machines.

The question that must be asked, is simply this. Which film, of the two, offers more in a cerebral sense? The answer, which would be obvious to most, is The Matrix. However, if I was to expand that question and ask which film offers the most in a broad-spectrum, sci-fi thriller action sense, then the answer is more clouded. And therein lies my difficulty with both films.

Equilibrium, I must be honest, was a film I stumbled upon by accident. Nobody told me about it, I just rented it one day from the video store, in a similar fashion to how I discovered The Boondock Saints. And I was utterly blown away by it: I couldn’t believe that the film was virtually unknown here in Australia, and after a bit of research on the Internet, I found that most people in the US hadn’t seen it either. Those that had said they felt it was a little bit of a Matrix rip-off, although I strongly disagree with that. Equilibrium has it’s own unique style, it’s own sense of purpose within the context of it’s narrative: it is stylistically similar, perhaps to The Matrix, but then, since The Matrix borrows so heavily from other genres of film (Chinese martial arts films, anyone?) then the point is, perhaps, a salacious one at best. Yet, for all it’s supposed similarities, The Matrix is perhaps a little too clever for itself.

I say that with the greatest respect, however; you can watch The Matrix multiple times and each time, gain something new from it. With Equilibrium, you cannot. A few views, and then you’re straight to the action scenes. There’s not the same level of thematic depth in Equilibrium. That said, I still think Equilibrium is a wonderful film, and can possibly hold it’s own against it’s older, bigger budgeted brother. Equilibrium has some wonderful action set pieces, and even beats The Matrix with some of the crazy antics captured on screen. The finale of Equilibrium, with Preston berserking through the governmental headquarters, mind and mission set, is stunning to watch, and one of the great “I punched the air with delight and cried out YES!” moments of cinema. For sheer exhortation-generating cinema, it’s hard to go past Equilibrium.

In the battle of cinematic heavyweights, The Matrix has won more than it’s fair share of bouts, up against some of the truly magnificent cinema achievements committed to the big screen format. It’s a towering achievement of a film, destined to be forever mentioned in the same breath as original Star Wars and Jaws for the impact to the artform they resultantly had. Equilibrium, however, will often be mentioned in the casual list of films you’ve never seen or heard of, and this in itself is a crime. Touted by Internet nerds as a Matrix-clone, Equilibrium is, I think, a genuine unearthed gem, and perhaps more valuable to cinema than most people realise. For many, I think the decision is a foregone conclusion, but I’d like to postulate that the points awarded to both films is more level than first thought. I have to bow to conventional wisdom for the result, awarding the victory to the film with a little more depth and thematic weight, The Matrix however, for me, the result is a lot closer than you’d normally expect.

I agree. The Matrix is overall the better script/movie, but Equilibrium has better fighting, and gun play.

I think you mean 'The Machinist', not 'the mechanic', in regards to Christian Bale's other movies.

Yeah, you'd be right. Thanks for the spot.