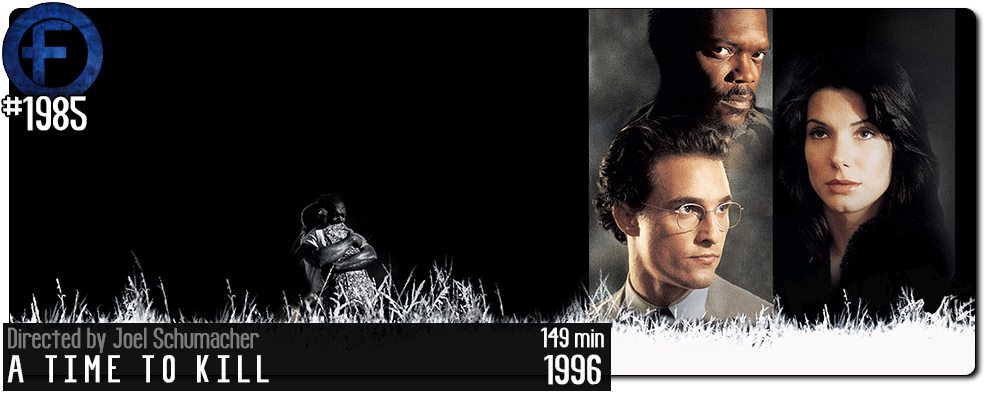

Movie Review – A Time To Kill

Principal Cast : Matthew McConaughey, Sandra Bullock, Samuel L Jackson, Kevin Spacey, Oliver Platt, Charles S Dutton, Brenda Fricker, Donald Sutherland, Kiefer Sutherland, Patrick McGoohan, Ashley Judd, Tonea Stewart, Chris Cooper, Nicky Katt, Doug Hutchison, Kurtwood Smith, Anthony Heald, M Emmet Walsh, Octavia Spencer, Rae’Ven Larrymore Kelly, John Seneca, John Diehl, Thomas Merdis, Alexandra Kyle.

Synopsis: In Canton, Mississippi, a fearless young lawyer and his assistant defend a black man accused of murdering two white men who raped his ten-year-old daughter, inciting violent retribution and revenge from the Ku Klux Klan.

********

Boasting one of the most astonishing cast rosters ever assembled, Joel Schumacher’s 1996 courtroom drama – based on John Grisham’s novel of the same name – is evocative, compelling and frustratingly atonal, resulting in a mishmash of homogenous prejudicial combativeness sieved through the sweaty, Klan-inflected Deep South of America’s racist present. The characters might have seemed “torn from the headlines” of the mid-90’s but today the film feels pressurised into delivering its message with the weight of a sledgehammer, led by a convicting Matthew McConaughey and a scintillating Samuel L Jackson. The film’s central plot – a distraught father murders his young daughter’s rapists in a fit of rage, only to find himself on trial for his life – is a hot-button issue and gristle-stoking ethical dilemma, pounded out between court sequences between weirdly comedic Ku Klux Klan machinations that don’t work (at least not always), but the joy of A Time To Kill is watching this stellar cast do their thing, Joel Schumacher’s restrained direction honing this piece into some serious awards bait.

When a ten year old girl, Tonya Hailey (Rae’Ven Larrymore Kelly) is kidnapped and sexually assaulted by a pair of local drunk rednecks (Nicky Katt and Doug Hutchison), the girl’s father Carl Lee is distraught with rage. When the pair are about to appear in court, Carl Lee mows them down with a machine gun, killing them and seriously wounding a local police officer, Deputy Sherriff Dwayne Looney (Chris Cooper). Arrested for double homicide, Carl Lee engages the services of young lawyer Jake Brigance (Matthew McConaughey), himself the father of a young girl and married to the beautiful Carla (Ashley Judd). Initially willing to take the case, against the protestations of his law partner Harry Rex (Oliver Platt) and one-time mentor Lucien Wilbanks (Donald Sutherland), Jake finds himself menaced by the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, after the brother of one of the murdered men (Kiefer Sutherland) seeks revenge. Against the superior talents of District Attorney Rufus Buckley (Kevin Spacey) and a prejudiced judge (Patrick McGoohan), and aided by upstart wannabe lawyer Ellen Roark (Sandra Bullock), Jake must fight both his own prejudice and the powers moving around him to save Carl Lee from the gas chamber.

My lord, just look at who’s in this film! You know you’re onto a cracker when even top-line talent like M Emmett Walsh, Chris Cooper and Donald Sutherland are reduced to secondary bit-parts simply because the film could. Hell, you blink once and completely miss an early Octavia Spencer appearance too! Based on John Grisham’s novel published in 1989, director Joel Schumacher takes one of the deepest, most complete casts ever assembled in the 90’s and wrings every ounce of mildly confrontational, superficially piercing civil rights and racially charged stories from the plot he can. The plot of Grisham’s novel remains largely intact, although some of the events within are portrayed by different characters or repurposed for the sake of narrative simplicity. One of the more egregious changes (in my opinion) is in the film’s climactic courtroom sequence – spoiler alert for a film over twenty years old! – in which McConaughey’s lawyer character challenges the jury to think of Tonya Hailey as a white girl rather than a black girl; in the novel, it’s a member of the jury who achieves this feat in the racially charged Deep South, and presents something of a White Saviour trope in achieving this. This twist is validated by an earlier scene in which Jackson’s imprisoned double-murderer exhorts McConaughey’s Jake Brigance to realising that he, a white man, is the Bad Guy in every scenario, and that Carl Lee is in a no-win situation simply because of his skin colour.

Radical complexity is handled with both underwhelming grace by Jackson and a fair amount of blandness by an earnest McConaughey, abetted by a potboiler screenplay by Akiva Goldsman, a Hollywood writer who has straddled both sides of the quality spectrum with both 1998’s Lost in Space, one of the worst films of the decade, and 2001’s Oscar-winning A Beautiful Mind. The clichés and deficient depth afforded this film is only mitigated by the stellar cast, all of whom do a lot of work in a wide ensemble to elevate pretty pedestrian material. The fact that the film tackles themes of white supremacy and deep-seated racism in America, evoking the country’s all-too-prescient present with the inclusion of the Ku Klux Klan as the central villains of the piece, shouldn’t avert the film’s mendacity in really getting to the core of the characters, none of whom make a compelling reason to remember this movie. Oh, A Time To Kill isn’t salacious or insipid with the representation in the story, it just does nothing interesting with it, or adequately promote McConaughey’s character’s journey from hotshot young legal eagle to forthright bringer of moral justice enough to make the arc work. In truth, there’s probably too many sidebar characters to pay attention to (Oliver Platt, as much as I love the dude, is wasted in a role designed simply to exist for no reason at all) to make Jake Brigance’s all-American virtuous paragon seem as cathartic as it needs to be. Parallels between McConaughey’s role in A Time To Kill and Kevin Costner’s also court-bound role in JFK are evident, utilising the upright “America is worthy of your time” motif and belief in the system – despite it being indisputably fallible to those not white, rich, or both.

Goldsman’s screenplay endeavours to get all nasty with the Klan appearing, spouting N-words and exhausting hate from the pivotal role played by Kiefer Sutherland, sporting a sweet crewcut and a cutoff denim jacket to emblemise the racially prejudiced archetypes America continues to deal with. Sutherland’s role as the prototypical Angry Young Man character out of revenge, as ironic as you can get given the initial inciting incident is among the most abhorrent of crimes (and is recounted in brutal, excruciating detail in the film’s climax) is an approximation of hatred for Black Americans, more a caricature or Low Hanging Fruit representation of the type, rather than anything more complex – it’s worth noting that racism has been, and continues to be, one of the major issues permeating American culture even today, and our conversations around this subject today are far more Daedalian than they were in the 1990’s. That Goldsman isn’t given enough time to really weigh in on some of the film’s story points in a film running some two and a half hours is telling of just how much material he had to whittle down from Grisham’s text, and just how difficult it must have been for both he and Schumacher to turn into a compelling and commercially accessible feature film. It’s a screenplay I don’t think goes quite far enough, not withering enough in its commentary on racial structures in America, but I think that’s more to do with Schumacher’s direction of it than either the writing or the acting.

White it might have worked in Grisham’s novel, which would have allowed internal thoughts to play out on the page, the disconcerting love-triangle aspect of A Time To Kill is the one crucial thing that undercuts the seriousness of the story. Jake, happily married to the gorgeous Carla (a near-constantly sweaty Ashley Judd) packs her off to a distant state once threats on their lives start to come in, before proceeding to flirt and dally with the intentions of Sandra Bullock’s headstrong Ellen Roark, a more kindred spirit to the suddenly lonesome husband, who finds herself attracted to the up-and-coming lawyer as they share trial and tribulation. Normally, a romantic triple-play would work in any other kind of film, but in A Time To Kill it feels tonally off, unsuited to the majority of the material and an unnecessary distraction from the central plot – it certainly doesn’t augment the rest of the movie. Watching a lad as likeable as McConaughey struggle with temptation of Bullock’s enigmatic behaviour gives a distinctly icky feeling to the viewer, and the film resolves this subplot quite poorly considering how much time we spend dealing with it. Neither Bullock or McConaughey take backwards steps with their respective roles – in fact, both are really, really solid in them – but the choice to include this element of Grisham’s book turns out to be a bit of a poor one.

The rest of the film is really quite sturdy under scrutiny, and I again return to the point that the film is peppered with a who’s who of Hollywood talent – the likes of Charles S Dutton, Brenda Fricker, Anthony Heald and Kurtwood Smith, normally able to command solid lead roles in most other movies, provide annexation support to the main stars – and when you have the likes of Doug Hutchison, who would play a similarly asshole role in Frank Darabont’s The Green Mile, almost unrecognisable as one of the antagonists slaughtered by Carl Lee in the film’s first act, you know you have a film more skewed to spotting famous faces than concentrating on the story. Kiefer Sutherland’s permanently sozzled deregistered lawyer character, a mentor to Jake before the film opens, offers the actor a chance to delicately play the ham, his knowing winks, glint-in-the-eye cheek and salubrious charm always welcome to the viewer – a marked contrast from the character his son plays elsewhere in the film – and he’s abetted by an equally garrulous Patrick McGoohan, best known for playing Edward Longshanks in Mel Gibson’s Braveheart, as the judge presiding over Carl Lee’s case.

Perhaps the most surprising element of A Time To Kill is Joel Schumacher’s direction, which hovers between a semi-serious dramatic urgency and a fanciful showmanship allowing for a more commercial product. Remember, A Time To Kill came along between his popular Batman Forever and the egregiously shit Batman + Robin; Shumacher’s polarising output was propelled by both the Batman franchise and popular dramatic films such as The Lost Boys, Flatliners, Falling Down and The Client, a journeyman director in the vein of Rob Cohen or Ron Howard, and with A Time To Kill he brings his homogenous visual style to bear on quite the pitchfork-bearing story. There’s a perfunctory exactness to Schumacher’s work here, many of the camera angles and editorial choices rather staid and plain, but these are offset by some flourishes from time to time that drag this movie from simple “made for TV” quality to big-screen worthy. Aussie cinematographer Peter Menzies Jr, noted for his work on Roger Donaldson’s The Getaway and John McTiernan’s Die Hard With A Vengeance, and more recently for his photographic work on the Peter Rabbit feature film franchise, brings an earthy brown-hued tone to the film, from the poorer sections of the town of Canton to the wood-panelled cavernousness of the courtroom, lit with what appears to be large natural light. The film doesn’t shy away from the heinousness of the initial crime of rape, or the slaughter of the two main douchebags at the centre of the case, and Menzies’ lensing of the film doesn’t portray the characters in particularly soft-focussed glory; instead, every bead of sweat, every nugget of grime or grit, every thread of frayed clothing to accompany frayed nerves and disjointed ethics, is shot with a crisp, unflinching style and colour palette.

A Time To Kill is one of those films that seems better than it is mainly because of casting, casting, casting. Having such an all-star, all-time powerhouse roster of talent at your disposal can make even the most mawkish, most earnestly delivered line read sound like Shakespeare at times, and Goldsman’s uneven screenplay certainly requires it. There are moments of pure screen magic – one of the film’s best scenes involves a confrontation between McConaughey and Samuel L Jackson, in which the latter espouses the fortunes and prejudice of the former – but there are missteps and not-quite-perfect moments punctuating the potential to its detriment. A film with such a wide-ranging ensemble and focus on a variety of competing subplots bulges with both issues of pacing and issues of complexity; A Time To Kill isn’t sharp enough to really excoriate the central plot with the white-hot concern it pretends to, but it’s fun to watch everyone on screen have a blast having a go. Perhaps the overly produced commerciality of A Time To Kill’s trailer-worthy logline makes a film positioned to deliver a supercharged diatribe on prejudice and racial inequality feel rather anachronistic by today’s standards, for it all feels a little too on-the-nose compared to other (more recent) stories of this kind, but that doesn’t take away from the joy of watching such a mind-blowing cast deliver above-standard performances in achieving this success. A worthy effort overall, lacking a true gut-punch resolution (instead, it’s all Grand Orchestra Salute faux triumph-anciful Americana) and undercutting the tonal imbalance with a woefully unneeded romantic subplot that hurts the overall result.