Movie Review – Breakfast Club, The

Principal Cast : Emilio Estevez, Molly Ringwald, Judd Nelson, Anthony Michael Hall, Ally Sheedy, Paul Gleeson, John Kapelos, Ron Dean.

Synopsis: Five high school students meet in Saturday detention and discover how they have a lot more in common than they thought.

********

Perennially popular 80’s classics don’t come more highly regarded than John Hughes’ The Breakfast Club, a touchstone moment in American cinema that remains among the most beloved, referenced and imitated of all the late director’s films. It boasts stellar performances from the five young leading roles, particularly Judd Nelson and Molly Ringwald, and amazingly encapsulated the disenfranchisement of youth, the rebellious angst felt by the disaffected, and the social outsider-ism prevalent at the time that, sadly, remains even more disconcerting today. The success of Hughes’ comedy writing for National Lampoons had led to his directing Sixteen Candles, which starred Molly Ringwald and Anthony Michael Hall and debuted a year prior, in 1984. Hughes re-cast Ringwald and Hall in his follow-up film, The Breakfast Club, which took a slightly different tack in the director’s ubiquitous coming-of-age subgenre, having the five representative students of the film sitting in a school library for the entire time, riffing on issues and prejudices ripe for exploration. The cultural reverberations of The Breakfast Club’s sizzling character interplay continue to be felt today, a shout of piercing truth to how teenagers often feel against the ebb and flow of social expectations and outside pressures.

In mid-1984, five students arrive at Shermer High School to begin all-day Saturday detention, overseen by Vice Principal Vernon (Richard Gleason). Sequestered in the library to write an essay about themselves, the five students – the athletic sports jock Andrew Clark (Emilio Estevez), school princess Claire Standish (Molly Ringwald), brainy nerd Brian Johnson (Anthony Michael Hall), kleptomaniac outsider Allison Reynolds (Ally Sheedy), and rebellious antisocialite John Bender (Judd Nelson) – initially resent each other’s presence, before their communal experience of internment brings out honest feelings and interweaving relationships. As the day progresses, they all discover that various pressures, from parents, school and their friends, are cross-clique issues that each must confront and work through, some with less struggle than the other.

Thematically, The Breakfast Club is a film that transcends the era in which it was made. Hughes’ archetypal school characters, from the jocks, the goths, the nerds, the princesses, have always been prevalent in modern society and bypassing the passage of time continue to do so even now. That the film is as timely and prescient with its messages of acceptance, empathy and first impressions, is perhaps its strongest element, and goes a long way to explaining why the film continues to resonate down the decades. Notably, the film doesn’t hold back with tackling urgent issues of the day, including suicide, with Emilio Estevez delivering one of the most powerful monologues of the decade as a defining third-act moment of revelation, Hughes’ writing nailing the angst and juvenile frustration felt by many a teenage kid perfectly. He interweaves their fears, their hopes and dreams, as well as their sorrows, with effortless ease, using Judd Nelson’s antagonistic Bender to instigate many of the conversations within. There is a large degree of intimidation from Gleason’s reprehensibly bullyish teacher role, which sparks several heated conversations over confronting authority figures who step too far, and the way Nelson’s character caustically attacks his classmates verbally is (obviously) a coping mechanism leading to eventual personal ruin. That John Bender is seen as “a loser” by the teaching fraternity – and obviously by his parents – forces the kid to misbehave, and I suspect a lot of kids who feel rejected by the adults in their lives will find themselves reflected in Nelson’s subtle, influential performance.

In contrast, Molly Ringwald’s socialite princess archetype is far more empathetic to the plight of those with her in detention, although the eye-roll dismissiveness she has for others waxes and wanes as the story unfolds. Although Hughes doesn’t go heavy on the tropes her character might invoke through a dramatic chamber piece like this, he allows Ringwald the width to explore peer pressure anxiety to conform to a specific set of expectations, such as sexual promiscuity, wealth and influence within both her school and extracurricular life. Ringwald, who was only 17 at the time the film debuted, exhibits a sprightly camera prescience and chemistry with Nelson’s Bender, and plays the superficially shallow Claire with a pretty in pink vibrancy that makes her perhaps the most accessible character in the film. Accompanying her as one of the film’s stronger roles is Emilio Estevez, the spitting-image son of Martin Sheen, as Andrew Clark, a short-statured but vigorously masculine sports jock who is continually baited by Bender to reveal more and more about himself as the film progresses. Estevez is initially restrained and kind of an Everyman character, but showcases a range of acting belying his comparatively young age – Estevez was in his early 20’s at the time, and The Breakfast Club became his breakout role. His single take monologue that cracks the interpersonal eggshells they’d all been walking on is a true highlight and arguably the moment the film takes its steps from teenage inanity to adult concepts; Estevez is easily the more mature of the young cast, and his showcase of range indicates that talent can be genetic.

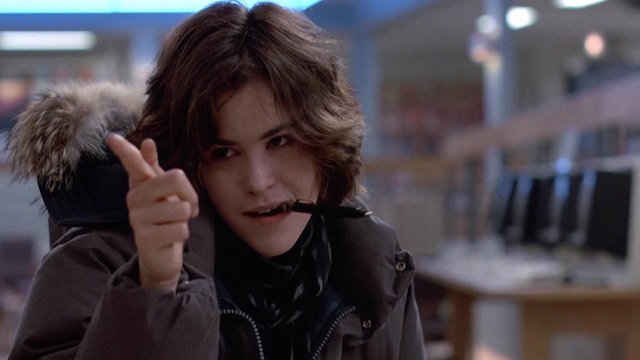

Rounding out the quintet are Anthony Michael Hall and Ally Sheedy, who, in somewhat “lesser” supporting roles have limited ability to prove themselves, with their characters far more reactive than proactive throughout. Sheedy had been a co-star alongside Ferris Bueller star Matthew Broderick a year prior, in War Games, and would follow up Breakfast Club by appearing alongside Steve Guttenberg in Short Circuit, in 1986, but her role here is far less about performance than it is simply looks; it’s a stereotype cliché Hughes plays with about judging a book by its cover, marking Sheedy’s dour, almost Gothically insecure “weirdo” as the least likeable before turning her literally into a princess in the final scenes – one might have half expected her to warble “You’re the one that I want” as she stepped in front of the cameras all make-upped and tousled, concluding one of the less successful arcs in the film with a whimper. Anthony Michael Hall’s character is also one of the weaker elements of the film, prone to reacting to occurrences within the story rather than instigating any actions himself. The script offers him up as a nerdy, brainiac type, whose parents have placed him under immense pressure to succeed – it’s he who intimates the suicide theme after receiving an F in shop class, the guilt of which he battles with constantly. Of the five students represented, I found Hall’s Brian the most forgettable, despite what the film’s title track might suggest.

At a brisk 90-odd minutes, The Breakfast Club wastes no time getting into its groove, and despite relatively little action to speak of, is constantly on the move and filled with honest beats of character, emotion and dramatic urgency. The film is also far more adult with its explorations of themes than I recall when I saw it as a teenager myself back in the day; while there’s a lot of vulgarity, it never feels written in to be controversial: Hughes had a way of tapping into the language of the day and while I suspect The Breakfast Club is far more sanitised with its language than actually existed at the time (or even now), there’s an urban grittiness, a dislocated sense of honesty to the dialogue and language used by the various characters. Estevez’ character even tut-tutts the use of bad language at one point, something I chuckled at because at no point in my schooling life did any of my classmates ever try and censure what another would speak, regardless of attitude. The thing about The Breakfast Club is that it opens a dialogue for people to see themselves reflected in some way within one of the characters presented here, and that speaks volumes to broader conversations about social attitudes within our youth sector.

Disaffected and misunderstood teenagers have been fodder for Hollywood’s insatiable pipeline for decades. From James Dean’s Rebel Without A Cause, Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, mid-80’s classics such as The Outsiders, Footloose and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, to the early 90’s scorchers like Heathers, Boyz N The Hood, and Pump Up The Volume, teen rebellion flicks have been a staple for generations, and will likely continue to be. John Hughes filmography remains perhaps the definitive article on coming-of-age dramatic comedy cinema, and The Breakfast Club is arguably the most famous of all, with the delightful cast encapsulating the simmering frustration, anger and loneliness of being a teenager in America. Although attitudes to sexuality, race and belief may have morphed into something else entirely today, The Breakfast Club’s honesty and refreshing presentation (despite not containing a single ethnic minority character – no race other than white) remains compellingly prescient even though it was filmed nearly 40 years ago.

A perfect coalescence of actors, terrific writing, and the rise of middle-class American angst in the wake of unbridled wealth generation during the 1980’s, The Breakfast Club remains an enduring classic for the reason it is so delightfully delivered. It touches on themes of sexuality, of appearance, of rebelling against authority, among other things, and I think these elements formed a perfect storm of head-nodding by willing teenage audiences who saw it. The Breakfast Club is a charming, effortlessly engaging dramatic work that maintains interest with its small cast and minimal locations thanks to Hughes’ pitch-perfect writing, and is a masterclass in character development. Don’t forget about this one.