Movie Review – Unforgiven (1992)

Principal Cast : Clint Eastwood, Gene Hackman, Morgan Freeman, Richard Harris, Jaimz Woolvett, Saul Rubinek, Frances Fisher, Anna Thomson, David Mucci, Rob Campbell, Anthony James, Tara Dawn Frederick, Beverley Elliot, Liisa Repo-Martell, Josie Smith, Cherrilene Cardinal, Shane Meier, Aline Levasseur, Ron White, Jeremy Ratchford, John Pyper-Ferguson, Jefferson Mappin, Mina E Mina, Henry Kope, Lochlyn Munro.

Synopsis: Retired Old West gunslinger William Munny reluctantly takes on one last job, with the help of his old partner Ned Logan and a young man, The “Schofield Kid.”

********

Dedicated to his cinematic mentors Don Siegel and Sergio Leone, Clint Eastwood’s masterful Western Unforgiven exactly extrapolates from those directorial luminaries the personification of masculine deconstruction, a violent and despair-ridden fable of broken humanity and anti-heroes, and trumps many of its subgenre brethren. Unforgiven notably won Best Picture over the likes of Howards End, Scent Of A Woman and A Few Good Men, and has endured as a cultural icon of Eastwood’s sterling directorial career as well as one of the greatest American Westerns ever made, stripping back the strong, silent hero of the genre into a complex, traumatically aspirational character of torment and guilt, assuaged by a reverence for his dead wife despite a feeling of intractable fatalism as his deadly mission begins to manifest.

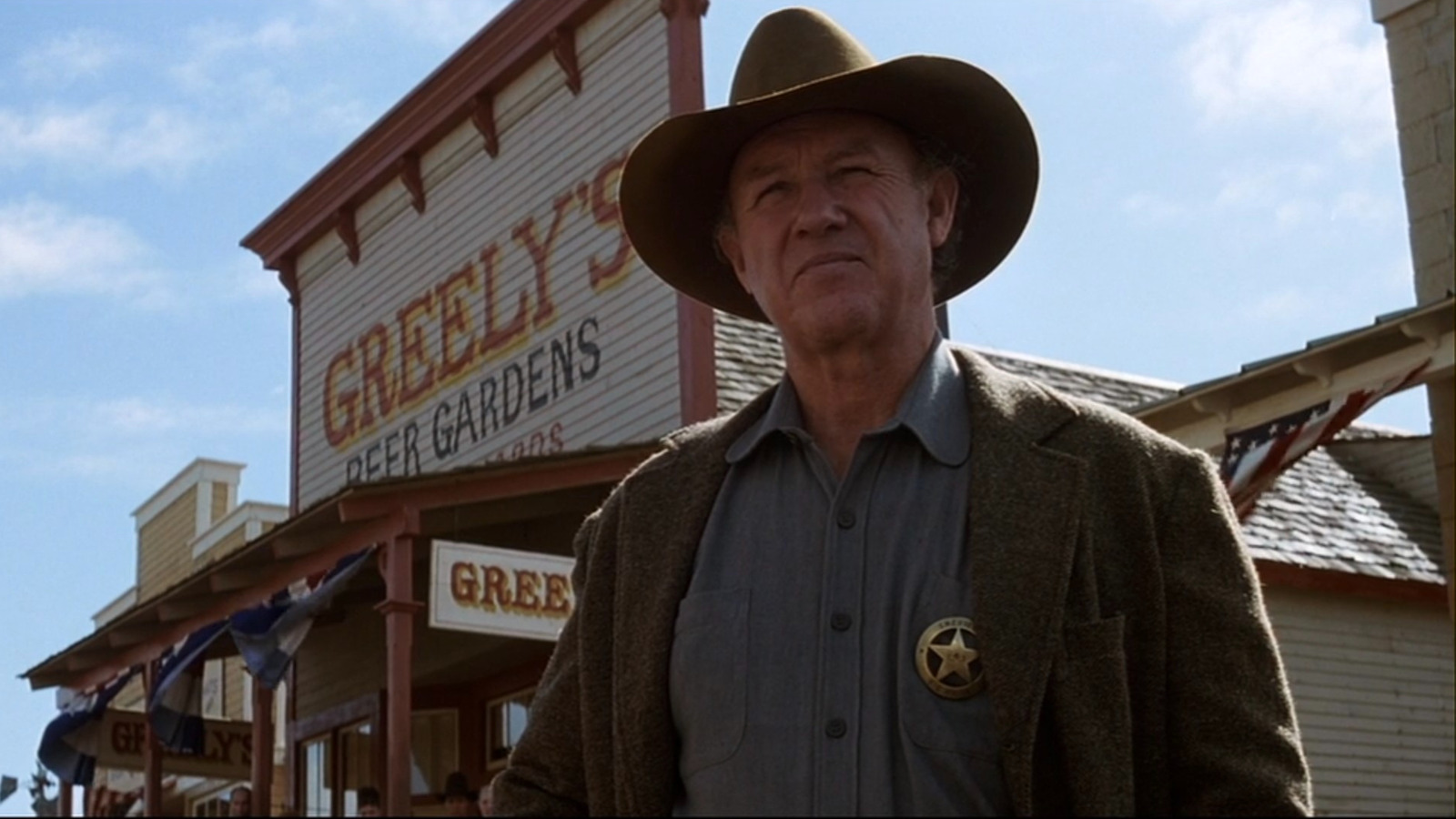

Written by Blade Runner and Ladyhawke scribe David Peoples, Unforgiven’s primary claim to fame is as an early modern example of deconstructing the hitherto heroic Cowboy Western’s typically black and white outlook on American history; morally grey central characters, ambiguous violence and an underpinning of gritty realism form the tableau against which Eastwood’s steady, commanding directorial style intrigues and entertains, a far cry from the brighter outlook espoused by the likes of John Ford or Stanley Kramer. In years past Eastwood’s characters were less profoundly human, more uber-heroic, and so Unforgiven’s grimier real-world aesthetic removes a weight of this expectation and turns him into an ageing father hoping his past never catches up with him. Peoples’ screenplay leans heavily into the substantive dichotomy of masculine pride, harsh frontier life and the valueless cost of humanity existing in this period of American history, with even the law- personified by a hypnotic turn from Gene Hackman – a less-than perfect exemplar of greed, corruption and hubris. The trade-off for Eastwood’s has-been anti-hero William Munny, historically a violent sociopath now living a redemptive rural life with his kids, between catharsis and vengeance is one of post-modern tragedy. A man described as the worst of the worst in a former life, now having made his peace, being drawn back into that life again, forces us as viewers to confront the notion of an empathetic man just trying to live, rather than an emblematic capital-V villain.

In 1881, William Munny (Eastwood) lives a widower life on his Kansas pig farm with his two young children (Shane Meier and Aline Levasseur), when he is called upon by a local mercenary going by the name “The Schofield Kid” (Jaimz Woolvett – Dead Presidents, The Guilty) to travel to Wyoming to kill a pair of cowboys accused of cutting up a local prostitute, Delilah (Anna Thomson – The Crow, Heaven’s Gate), and claim a $1000 reward. Munny, recruits a friend and colleague, Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman) to accompany them and split the reward, with the trio setting off to the small frontier town of Big Whiskey. Standing in their way is the cruel sheriff Little Bill Daggett (Hackman), who rules Big Whiskey with an iron fist, running off any vagrant or mercenary who comes calling to claim the money; the arrival of British shootist English Bob (Richard Harris – Gladiator) and his biographer, WW Beauchamp (Saul Rubinek – Nixon, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs) sees the small group of harlots, led by the feisty Strawberry Alice (Frances Fisher – Titanic), realise that revenge for Delilah’s injuries will soon be meted out, and they soon find a kindred spirit in the craggy violence of Munny’s reprisals.

Unforgiven sits right on the cusp of being an unadulterated masterpiece. Its reputation as one of the best Westerns ever made is sublimely earned: everything about the film is eloquently serendipitous, from Peoples’ screenplay, the production design, the acting, the direction, and of course the music. The film feels like a eulogy in many ways, a film in which Eastwood buries the lustre of his 70’s cowboy era within a framework of violent reprisals, haunting (and haunted) character portrayals, and a crisp, solidly directed narrative with characters that feel lived in and real. Unashamedly stoic behind the camera, and definitively brilliant in front of it, Eastwood presents as a far more ragged, unkempt characterisation of his early career, in which his square jaw and flintlock glare froze many a bad guy into submission, and I would argue that of all his modern films this is his singular, career-defining performance. Equally as career-defining is the performance of Gene Hackman as Little Bill, as ferocious a cowboy archetype villain as there has ever been considering the character is the sheriff, and the actor deservedly snagged an Oscar in the Supporting Role category: Little Bill is, similarly to Munny, a character of light and shade, capable of salvageable good and shuddering cruelty, espousing the duality of man in a single, fearsome screen turn. Hackman has such a screen presence he towers above all around him, even casting the legendary Richard Harris into the shade as he barks and bullies his way through the movie, eventually confronting Munny in the film’s famous climactic barroom shootout. Little wonder Sam Raimi cast him in an almost note-for-note similar role for The Quick & The Dead a few years later.

Peppered into various roles are a smattering of Hollywood royalty, notably the aforementioned Richard Harris, whose dulcet tones and intonations are a stark contrast alongside the drawling Western dialects employed by the rest of the cast. Harris’ role is notably minor but admirably effective, essentially a foil of Hackman’s Little Bill by way of demonstrating just how potent a force Hackman’s character is on the overall plot. Saul Rubinek’s glory-chasing writer character, WW Beauchamp, is played beautifully by the actor, almost with weasel-like affection for the characters he interacts with as he takes down mythological fables loosely based on real events. Frances Fisher plays the leader of the small band of hookers who inhabit Big Whiskey, and she’s as clear-eyed and superbly written as a harlot as any of the other characters within. It should be noted that Ann Thomson’s poor Delilah is also afforded a degree of humanity (in a world which dehumanises women considerably) turning her from a one-note role into a compelling, empathetic human being. The likes of Anthony James (who had a supporting role in another Eastwood film, High Plains Drifter) as the town’s barkeep, Morgan Freeman as Munny’s faithful offsider Ned, and Jaimz Woolvett’s Schofield Kid are all delightfully realised and fully fleshed out characters in their own right, with their eventual fates carrying real weight and impact as the film winds its way to the expected bloody conclusion. Woolvett’s performance is perhaps the film’s weakest element in terms of screen chemistry, coming off as a touch wooden, but by the time the film comes to an end even he can’t supplant Eastwood’s Munny as the defining element in retribution.

Capturing all this human angst is arguably one of the great feats of cinematography, performed by Jack N Green. Green, who had worked with Eastwood as DOP since Heartbreak Ridge, drapes the film’s sepia-toned visuals with a brown, tan and almost suffocating black colour palette that evokes an earthiness and humanity to the story. The daylight sequences always feel tinged with grey, a dour outlook on a cruel and unforgiving (ha!) world, whilst the plentiful night-time sequences are plunged into shadow and rain, bookended by hauntingly beautiful sunset photography for the film’s opening and closing shots; one has the sense that the film’s murky visuals are representative of the shady nature of the characters within, blemished and tarnished by the virulently violent landscape they inhabit. Green and Eastwood also make superb use of the split diopter shot, allowing focus for both foreground and background simultaneously, and this technical note is executed almost invisibly within the context of the story. Accompanying these visuals is a sublime score from Lennie Niehaus, who was inexplicably not nominated for an Academy Award, with one of the truly great Western themes afforded modern cinema that serves as an appropriately romanticised, if restrained, backing track to the violence depicted. There’s shades of Morricone in Niehaus’ score, echoes of a more familiar Eastwood aesthetic, but in Unforgiven it’s specifically chosen as a balance to the human tragedy before us; Niehaus’ central theme feels loving, almost nostalgic for a simpler time, when we can all see that the story and characters are far from simple.

Unforgiven isn’t just a great Western, it’s a great movie. Populated by top-line actors supporting two magnetic turns from Eastwood and Hackman, terrific production design and typically restrained direction from the director, Unforgiven is a remarkable piece of commentary on popular culture afforded to the Cowboy genre. It’s an early example of the grimdark motifs of more adult fare, an assemblage of violent, dank characters simply trying to survive the Old West. The film is the contemporary polar opposite of both Tombstone, which arrived a year later in 1993, or Kevin Costner’s Wyatt Earp, which debuted a year after that again, and serves as a launching pad for the kind of despairing, adult-oriented examples of the subgenre’s de-Americanisation of its own myths; with the likes of Bone Tomahawk, 3.10 To Yuma, Open Range and the Coen Brothers’ remake of True Grit eschewing simplistic Good Vs Bad tropes and inviting introspective, nuanced examination of the nation’s frontier birth, they owe a modicum of fealty to the tone of Unforgiven. Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven is a thoroughly engaging, always watchable classic of the genre, arguably one of the most worthy Best Picture winners of the decade, and I would suggest perhaps is the high point of Eastwood’s legendary career behind the camera. I don’t think he’s ever bettered it.