Movie Review – Mary Poppins

Principal Cast : Julie Andrews, Dick van Dyke, David Tomlinson, Glynis Johns, Hermione Baddeley, Karen Dotrice, Matthew Garber, Elsa Lanchester, Arthur Treacher, Ed Wynn, Reginald Owen, Reta Shaw, Don Barclay, Arthur Malet, Jane Darwell.

Synopsis: In turn of the century London, a magical nanny employs music and adventure to help two neglected children become closer to their father.

********

A film that almost defies criticism, Disney’s 1964 Best Picture nominee was the subject of a protracted and wily battle of wills between the legendary filmmaker and the property’s creator, author PL Travers (most notably depicted in the film Saving Mr Banks); Mary Poppins has long been regarded as the crown jewel of the Walt Disney company’s live-action film back catalogue. Rightly nominated for a slew of other Oscars in mostly technical categories, Mary Poppins set a benchmark for its use of effects and filmmaking wizardry, with everything from wire work, forced perspective, reverse photography, matte paintings and model-work, puppetry and animatronics, rotoscoping and integrating live-action and animated characters within the same frame, to some of Hollywood’s most memorable songs and soundtrack cues and – of course – Julie Andrews’ breakout role (snagging her the Best Actress Oscar) as the titular magical nanny who comes down to shake-up the upper-class Banks household in early 20th Century London.

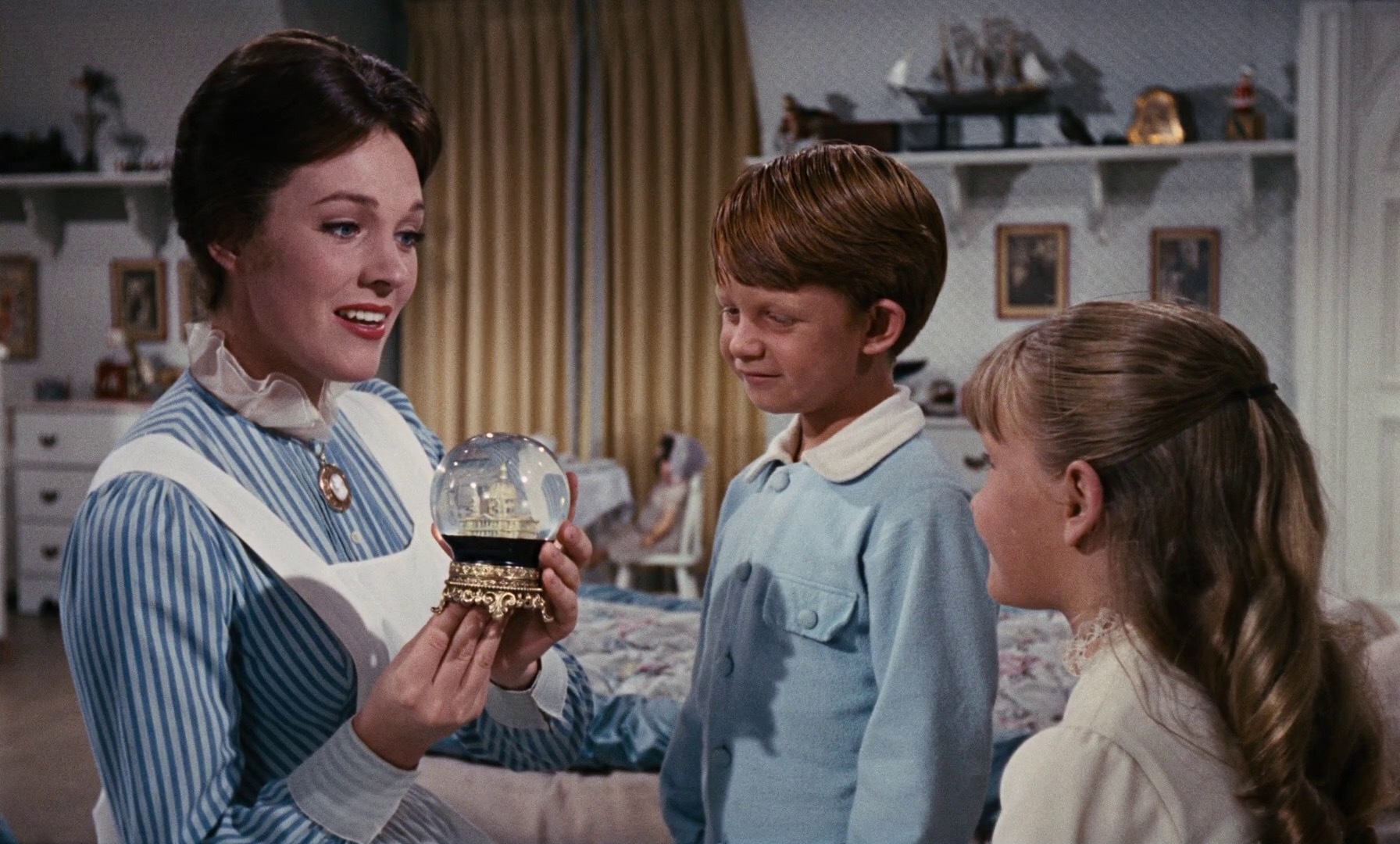

In London, 1910, England is undergoing a great period of commercial prosperity and social upheaval. Rising banking employee George Banks (David Tomlinson) lives in a well-to-do neighbourhood on Cherry Tree Lane, with his wife, suffragette Winifred Banks (Glynis Johns), two precocious children Jane (Karen Dotrice) and Michael (Matthew Garber), and their household staff (Rita Shaw and Hermione Baddeley). After the children’s latest nanny (Elsa Lanchester) quits in disgust, George sets about recruiting a new, no-nonsense replacement, only to have the enigmatic carpet-bag toting, bird-umbrella carrying Mary Poppins arrive and set about looking after the children. Following a series of comical and whimsical adventures alongside chimney-sweep Bert (Dick Van Dyke), Mary and the children are shocked to find George unceremoniously fired from the bank at which he works, although his final parting joke to the bank’s elderly and decrepit director Mr Daws (also Dick Van Dyke) sees a change of fortunes for the irascible Edwardian inhabitant.

I’m not afraid to admit that as a child, I always assumed Mary Poppins’ depiction of London and England was exactly what it was like. Imagine my surprise, then, to grow up and learn than not only is Dick Van Dyke’s vowel-destroying Cockney accent utterly abysmal but that there is no actual Cherry Tree Lane in London, and I’m led to believe that the chimney-sweep business was a pretty dangerous one in which nobody dances across rooftops or even jumps into chalk drawings for a summery natter at the races. This tearing down of the façade offered by Robert Stevenson’s eye-catching direction was a crushing blow, but this never once removed the luster or nostalgia for which my generation would approach this timeless, seminal movie.

Shot in the summer of 1963 using almost all available soundstage space on the Disney lot, Mary Poppins’ long gestating pre-production would see Disney court PL Travers for the films rights to the property; the author was famously combative with Walt Disney over his proposed treatment of the authors incredibly successful works, works of such personal nature Disney changed much of the structure of his original screenplay treatment to accommodate much of Travers’ concerns – one notable one was the softening of George Banks’ personality to make him less disagreeable and antagonistic, the result being David Tomlinson’s earnestly masculine yet utterly self-assured portrayal in the finished film. Screenwriters Bill Walsh and Don DaGradi worked with Disney and Travers over various iterations of the material, tweaking aspects of the characters until the author was satisfied they weren’t going to become 1-dimensional fluff, a concern she had had from the outset. Travers also objected to the use of musical numbers in the film – the Sherman Brothers work in Mary Poppins is perhaps their most famous of all – and reputedly despised the inserting of animated sequences into her material, so much so she kyboshed any further film adaptations of the books.

The result of nearly 20 years of persistence payed off for Disney and his team – Mary Poppins became the most successful box office film of the year (and reportedly Walt used the proceeds to fund his purchase of the land he would use to build Walt Disney World in Florida) and was nominated for a massive thirteen Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Screenplay, ultimately winning five including Best Actress, Best Song and Best Score. That it remains so popular even to this day – spawning a 2018 sequel in Mary Poppins Returns) – is testament to the love, care and attention to details the Disney studio put into the production, a quite literal “spare no expense” entertainment experience that remains as idyllic and nostalgic as it ever has.

Okay, so Dick Van Dyke’s accent might be quite problematic, and some of the film’s visual effects have dated poorly compared to modern filmmaking techniques, but the undeniable magic of Poppins seeps through every frame of this musical wonderland. Although lauded far and wide at the time, Julie Andrews’ Mary isn’t really even the center of the story – that facet belongs to David Tomlinson’s George Banks, through whom we learn to stop thinking like an adult and re-embrace our inner child again – and the crucial element of the film’s enduring legacy is, in my opinion, the music and songs. Almost every tune is instantly memorable, from “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious” to “Chim Chim Cheree”, “Step In Time”, “A Spoonful of Sugar” and “Feed The Birds”, right down to the film’s closing number “Let’s Go Fly A Kite”, composers Richard and Robert Sherman gave the gift of lyrical magic to a film already bloated with wild ideas and a surfeit of imaginative conceits. Mary Poppins’ enduring appeal isn’t really about a magical nanny, or two upstart and misunderstood children, but rather the journey of discovery essayed by the Sherman Brothers’ gorgeous tunes and lyrics, and seminal accompanying score. The film aches for the magic of childhood, and assumes a childlike simplicity for the majority of its song list, although isn’t afraid to mature with confidence for “Feed The Birds”, arguably one of the most beautiful songs ever written for a Disney movie.

As Mary Poppins herself, Julie Andrews is the personification of prim and proper, a stern but fair nanny with a twinkle in the eye and a proclivity for offhandedly using magic whilst decrying thoughts of whimsy. Andrews singing talent is equally up to the task of selling the role, delivering sprightly foot-tapping tunes and occasional soulful reverence without missing a beat as the story demands. Her on-screen comedy relief is Dick Van Dyke, who fumbles, bumbles and pratfalls his way through what might be an interminable roster of facial expressions and overplayed comedic beats were it not for his fellow cast’s amenable personality. Van Dyke pulls double duty not only as Bert the chimney-sweep, but also (in my mind an even funnier role) the nonagenarian bank owner Mr Dawes, a scattered and physically intransigent amalgamation of Edwardian British stereotypes. Frankly, Van Dyke’s best work comes as Mr Dawes attempts to scavenge tuppence from young Michael Dawes to invest in the bank, and the actor’s spectacular physicality is best served under the restraint afforded the character. Sure, Van Dyke has the charisma to lay Bert in spades but the comedic aspects of the role feel too hammy even for a film as magical as this; had the studio requested a little more restraint in the part, just enough to keep it from being too silly, I think the balance between Bert and Mary might have worked a lot better.

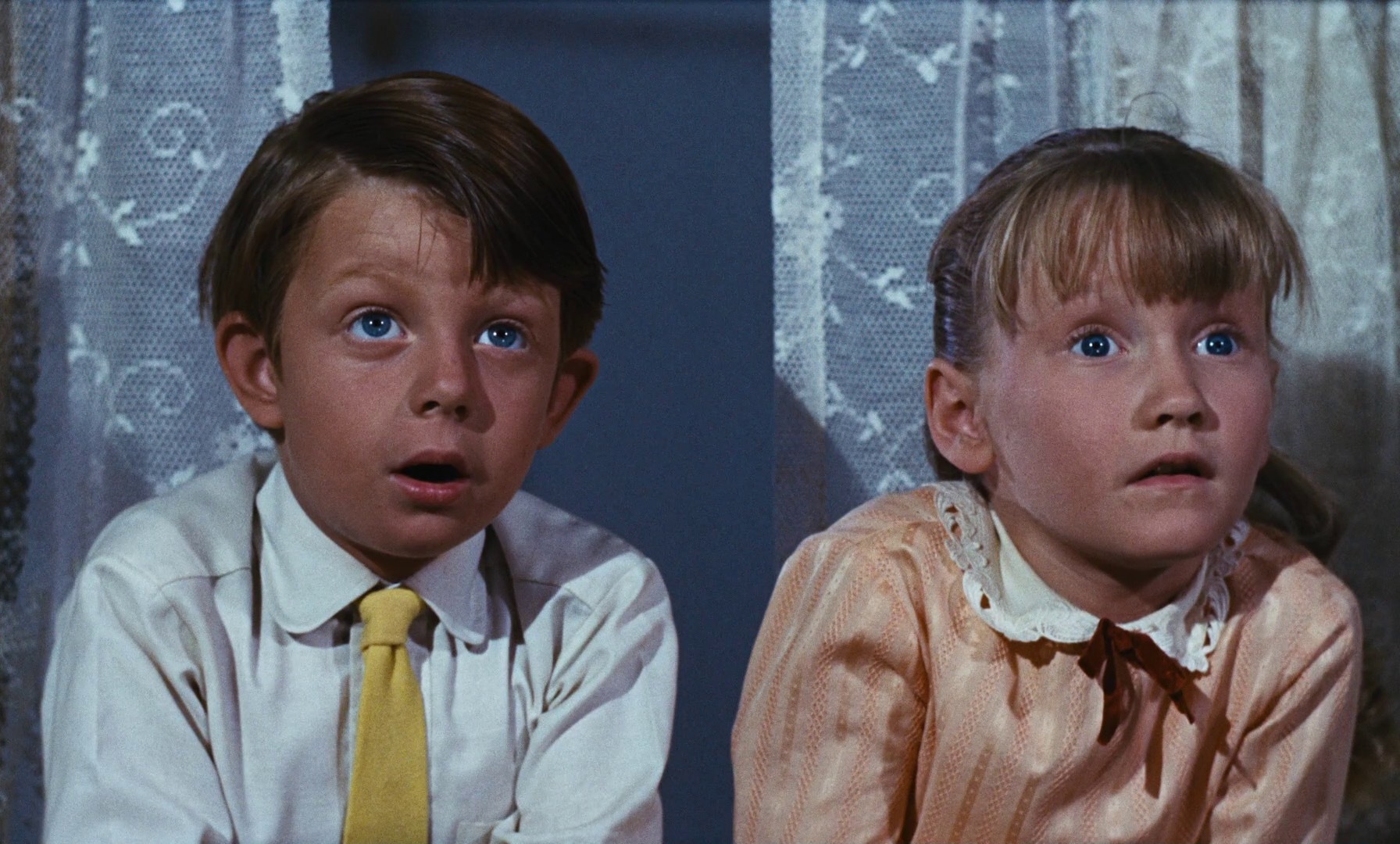

That said, a vast amount of the film’s tone comes from two places: the children, Jane and Michael Banks, and their father, George. Neither Karen Dotrice or Matthew Barber are particularly natural as the Banks children, but they serve as captivated awestruck viewers of Mary Poppins’ activities that forms the audience’s viewpoint of all the goings-on. Naturally they question everything and want to know how it all works, which is pretty much how we all view the film itself, trying to figure out the filmmaking mechanics behind a lot of the movies’ great visuals. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, is Tomlinson’s George Banks. George is a bit of a wanker to start with – he’s misogynistic, doesn’t listen, likes to talk and thinks pretty highly of himself. By the end of the film he’s worked out how to be a child again, playful and engaged with his family and open to new experiences and questions. It’s an arc the film takes some time developing and paying off, and I would argue Tomlinson’s arrival at, and firing from, the bank at which he works late in the film is among the actors more subtle performances. Being able to go from resigned melancholy to outright joy at the silliness of it all in one scene is testament to the actor’s ability to really understand the character, and its remarkable just how effective it is as the root of the viewers’ own preconceived notions of what is, essentially, a children’s fantasy for adults.

Eternally magical and fuelled by an innate sense of wonder, Disney’s Mary Poppins has a legacy that spans the decades since it debuted in 1964. Optimistic to a fault, stuffed to the brim with wonderful music, easy-to-watch characters and some staggering production design and visual effects, Mary Poppins remains the gold standard for the studio’s live action accomplishments, and one I am entirely sure is unlikely to be replicated during my lifetime. Endlessly inventive and filled with imagination, Mary Poppins is an all-time classic.