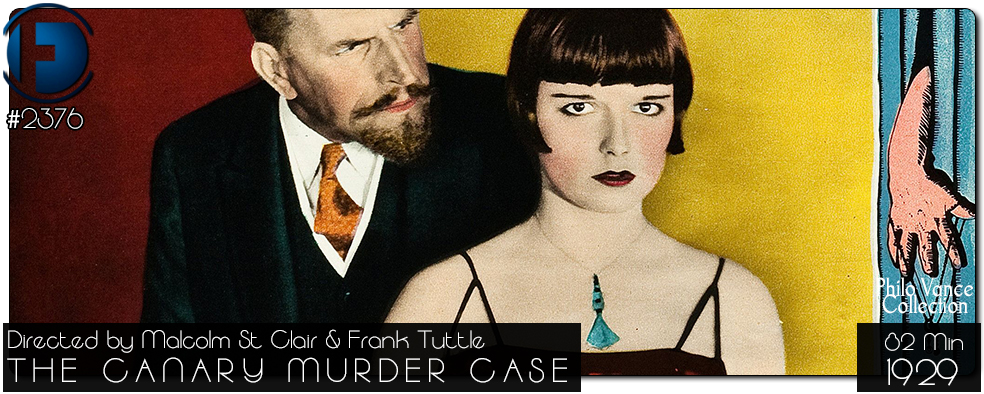

Movie Review – Canary Murder Case, The

Principal Cast : William Powell, Jean Arthur, James Hall, Louise Brooks, Charles Willis Lane, Lawrence Grant, Gustav von Seyffertitz, EH Calvert, Eugene Pallette, Ned Sparks, Louis John Bartels, Tim Adair, Dennis Morgan, Oscar Smith, Margaret Livingston.

Synopsis: Nightclub singer ‘the Canary’ blackmails acquaintances, ends up murdered. Only witness also killed. Detective Philo Vance investigates to uncover her killer among numerous suspects she had exploited.

********

Paramount’s first Philo Vance picture was originally filmed as a silent, however due to the popular uptake of “talkies” around the time of the film’s release in 1929, a lot of studios were redubbing their projects to release with the newfangled technology. The elements of the film’s silent picture origins are evident here, and reduce a lot of the pure enjoyment of the story and characters somewhat, but as a technical and historical exercise I as utterly fascinated by The Canary Murder Case, with the enigmatic but always watchable William Powell in the title role of SS Van Dine’s popular literary detective Philo Vance. Controversially for Paramount, actress Louise Brooks, who plays the titular “canary” of the film, refused point-blank to return to America to record her lines dubbed for the transition to sound, a decision which would affect her career significantly, leaving the studio no choice but to use an alternative actress – Margaret Livingston – to deliver the requisite tones of the cruel showgirl over Brooks’ acting performance.

Popular showgirl Margaret O’Dell (Louise Brooks), otherwise known as “The Canary” is a conniving, cruel mistress who lures men into a whirlpool of blackmail and deceit. The is scheming to marry the young Jimmy Spotswoode (James Hall) against his will, despite the protestations of his father, Charles (Charles Willis Lane), who beseeches O’Dell to give up. Meanwhile, a variety of older men also have designs of love on the Canary, using her sexual wiles to manipulate them into showering her with expensive jewels and gifts in lieu of revealing their respective infidelities to their wives and families. Eventually, O’Dell is found dead – strangled by a necklace – and as the District Attorney (EH Calvert) investigates with Sergeant Heath (Eugene Pallette), they recruit local amateur detective Philo Vance (Powell) to help them unravel the mystery of the killer’s identity.

Hollywood’s sudden interest in the then-nascent sound film technology, after decades of films being largely silent and accompanied by a live musical accompaniment, provides us with not just the first of the Philo Vance films made by Paramount, but also a marvellous little curio from the film industry’s earliest days. It surprised me to learn that The Canary Murder Case was filmed as a silent movie before being dubbed for sound release, because I figured that would be exorbitantly expensive for the time – it was, really, but the payoff of putting a movie in a sound-equipped cinema was far greater than the “old, outdated” silent film establishments of the day. The uniqueness of this effort, to put back into the film the sounds of the actor’s actual voices, often for the very first time, allows us to appreciate the film’s genesis and production a little more thoroughly, as The Canary Murder Case – along with numerous other just-completed silent pictures of the day – was given both a silent release and a sound release to maximise returns between newly upgraded cinemas and those who had not yet made the transition. The evidence of the film’s silent-movie production is plan for all to see, and the dubbing of the actors ranges from excellent to forgettable, and a number of times in the film an actor’s mouth will move on-screen without any line of dialogue to accompany it. Frank Tuttle, who would go on to direct this film’s sequel as well as one other in the Philo Vance series, was brought in to helm the various reshoots required to bring the film up to a fit state to release, as original director Malcolm St Clair, was unavailable.

Although this initial Philo Vance film is relatively clunky, with a scattered script that relies heavily on implication and exposition rather than action, it’s still wonderful to sit back and think upon how viewers of the late 1920’s would watch this in its initial run and marvel at Philo Vance’s deductive capacity and the “cleverness” of the murder plot, and perhaps be surprised at how great William Powell was in a then-rare protagonist role. Powell – as I’ve mentioned in my other reviews of the Philo Vance series so far – runs rings around the other actors he shares the screen with, and in truth the film struggles with the balance between silent film acting and sound film acting, with pregnant pauses, awkward line delivery (or perhaps awkward dubbing?) and some weird shot selections and editing making it a puzzling film to “enjoy”. As a fan of this period of cinema I appreciated the work of all involved, but could see how casual film fans or even newcomers to silent moviemaking might baulk at the crude nature of what St Clair was able to achieve.

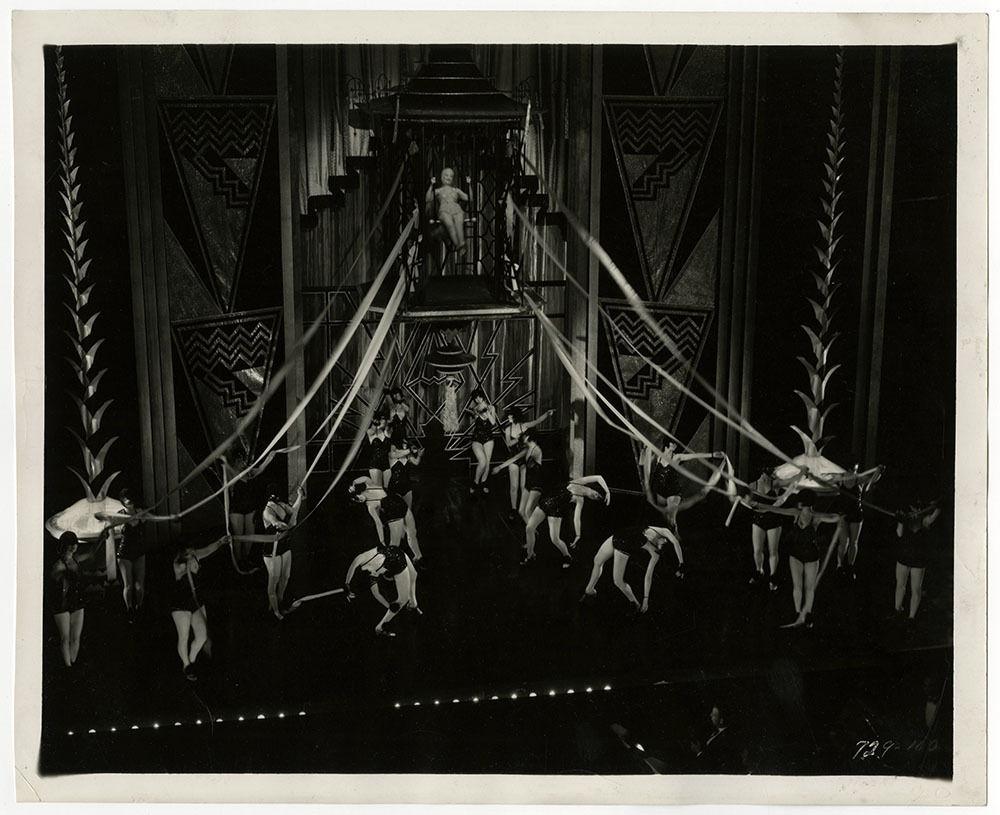

To be fair, the production design and some of the film’s visual effects are really wonderful to see. There’s a fluidity to Malcolm St Clair’s work with oblique overhead angles, terrific focus use for an early highwire sequence involving Brooks’ Margaret O’Dell, and some solid set design work mixed with great cinematography for the night scenes (all shot on a soundstage, mind), and props should be given to Harry Fishbeck as cinematographer (and an uncredited Cliff Blackstone – The Virginian) for his delightful work on this project. The available sound print shows its age, and you can really tell some of the older silent footage elements used to piece together a sound narrative (the interstitials on the silent version were crafted by none other than Herman J Mankiewicz, no less a screenplay writer for Citizen Kane, among others), and crucially Louise Brooks’ decision not to return to shoot additional footage mars some of her character’s work in the film’s opening act. Hard to really expand the character if it’s a stand-in shot from behind with another woman’s dubbing layered over it, I guess; it is what it is, and to be honest the character of Margaret O’Dell probably didn’t need a huge amount of additional development, given her fate and the fact the story revolves around her death.

Alongside Powell and the unfortunately insufficient Brooks, are series regulars EH Calvert, as the District Attorney, Eugene Pallette as the “comedy relief” in Sergeant Heath, while Jean Arthur appears as the romantic interest for James Hall. Arthur would also appear in the other 1929 Philo Vance film, The Greene Murder Case, as an entirely different character, and would eventually become one of the most in-demand actresses in Hollywood, appearing in such classics as Mr Deeds Goes To Town, The Plainsman, Mr Smith Goes To Washington, and A Foreign Affair. Charles Willis Lane is perhaps the second-best actor in the whole thing, as Charles Spotswoode, while James Hall, Lawrence Grant and the fantastically named Gustav von Seyffertitz all seem to struggle with escaping their stage-acting woodenness. Young Oscar Smith, known for his particular stutter, plays a hotel lobby boy and performed so well he was offered a long-term contract as an actor, a rarity for black performers of the time. I would posit that The Canary Murder Case isn’t a film with strong performances, I think mainly due to the piecemeal assemblage of the sound version late in the day, but it is definitely one to examine for its inventive camerawork, subtle editing, and often remarkable framing; again, props to Harry Fishbeck for some remarkably stylish work behind the lens.

The Canary Murder Case is all but unremarkable as an entrant in the early sound film legacy, and aside from some controversial aspects off-camera it’s been largely forgotten. Reappraising its charms in a modern context, one can find much to marvel at simply for its very existence, or that it makes as much sense as it does considering the brutal pace of the setup, second act twists and final reveal in contrast to more cerebral genre entries today. As with all the Philo Vance films, this debut is relatively brief, fast paced, and delights whenever William Powell appears on screen – and in a rarity, he’s on-screen from the get – and so I recommend it for completists, interested cineastes looking to expand their appreciation of early knockabout Hollywood, and those seeking an example of a troubled production overcoming a problematic leading lady and still managing to remain engaging.